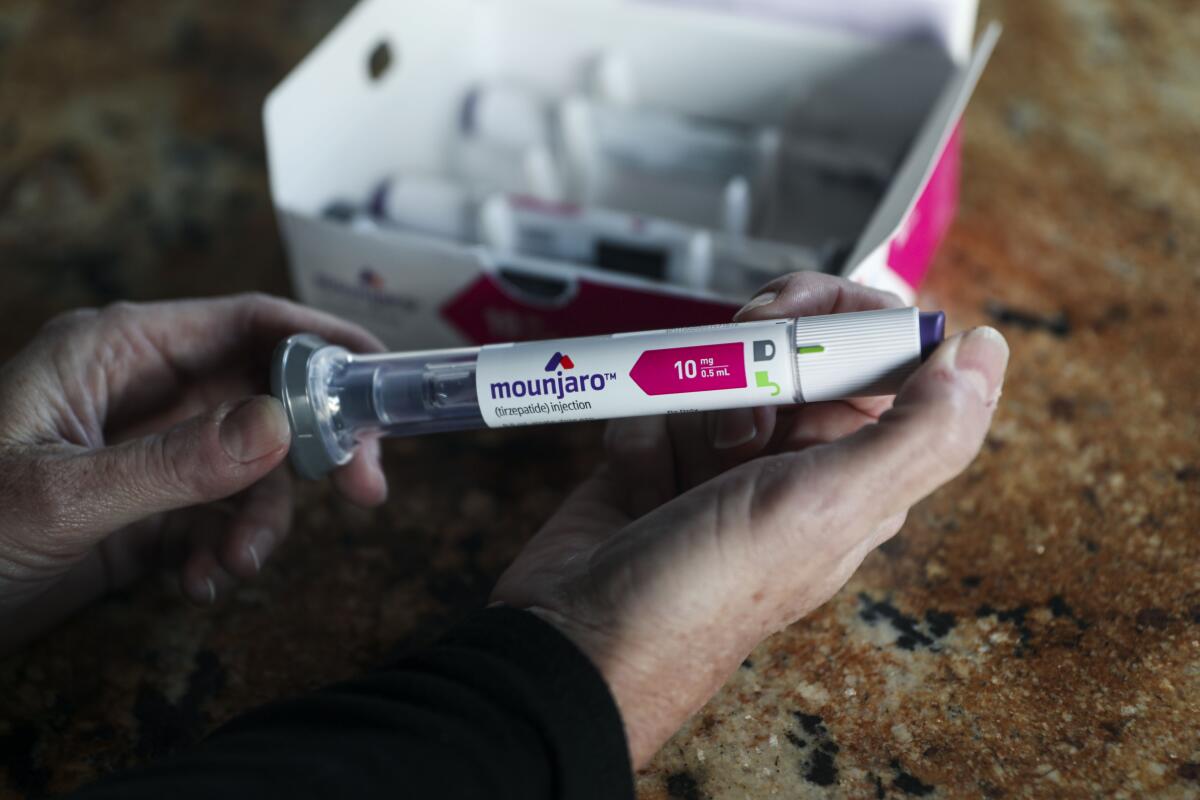

Mounjaro bests Ozempic for weight loss in first head-to-head comparison of real-world use

In the first head-to-head comparison of two blockbuster drugs used in real-world conditions, people who took Mounjaro lost significantly more weight than their counterparts who took Ozempic — and the longer the patients kept taking the drugs, the wider the gap became.

After three months of weekly injections, patients on Ozempic lost 3.6% of their body weight, on average, while those on Mounjaro lost an average of 5.9%.

At the six-month mark, Ozempic patients had dropped an average of 5.8% of their weight, while the average weight loss for Mounjaro patients was 10.1%.

And when a full year had passed, those taking Ozempic had lost an average of 8.3% of their weight, while those taking Mounjaro had shed an average of 15.3%.

The researchers who conducted the analysis also found that compared with people on Ozempic, those on Mounjaro were 2.5 times more likely to lose at least 10% of their initial weight and more than three times as likely to lose at least 15% of their weight during their first year on the medications.

The findings were published Monday in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Dr. Matthew Freeby, an endocrinologist and director of the Gonda Diabetes Center at UCLA’s Geffen School of Medicine, said the study results are in line with what he has observed in his own patients.

“From a weight-loss perspective, and from a sugar-lowering perspective for those with Type 2 diabetes, we see stronger effects with Mounjaro compared to Ozempic,” said Freeby, who was not involved in the research.

Ozempic and other drugs raised the possibility of reversing the country’s obesity crisis. Doctors are frustrated that they’ve made health disparities worse.

Both drugs were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to help people with diabetes keep their blood sugar under control. By mimicking a hormone called glucagon-like peptide 1, or GLP-1, they boost the body’s production of insulin, slow digestion, increase feelings of satiety and reduce appetite.

Mounjaro also imitates a related hormone called glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide, or GIP.

When the drugs were tested against placebos in clinical trials, both helped patients lose a significant amount of weight. Tirzepatide, the active ingredient in Mounjaro, appeared to be more effective than semaglutide, the active ingredient in Ozempic. But the trials weren’t conducted under the same conditions, so the results aren’t directly comparable.

Researchers from Truveta, a healthcare data and analytics company owned by 30 health systems, sought to remedy that by examining their trove of electronic health records. The work also gave them a chance to see how patients fared outside the idealized setting of a clinical trial, which typically provides free medication, regular check-ups and other types of support.

With the help of their database, the researchers were able to spot people who filled their first prescription for either drug between May 2022 — the month Mounjaro joined Ozempic in receiving FDA approval — and September 2023. Patients didn’t need to have Type 2 diabetes to be included in the study, but they did have to be overweight (with a body mass index of at least 27) or obese (with a BMI of at least 30).

The Truveta team found about 41,000 people across more than 30 states who met all their criteria for being included in the study. Since Ozempic patients outnumbered Mounjaro patients 3 to 1, the researchers used information on age, race, income, health history and other factors to come up with a group of Ozempic patients who most closely matched the Mounjaro patients. The result was a population of nearly 18,400 who were evenly split between the two drugs.

Before their first medication dose, the average weight for people in both groups was 243 pounds. But it didn’t take long for the two groups to diverge.

After accounting for unmeasured influences that could have skewed the results, the Truveta team found that the amount of weight lost was 2.4 percentage points higher for Mounjaro patients than for Ozempic patients after three months, 4.3 percentage points higher after six months, and 6.9 percentage points higher after a year.

Mounjaro also bested Ozempic in terms of people’s success in meeting various milestones within a year of starting on one of the drugs.

Nearly 82% of Mounjaro patients lost at least 5% of their body weight, compared with 67% of patients who took Ozempic. Likewise, 62% of Mounjaro patients and 37% of Ozempic patients lost at least 10% of their initial weight, while 42% of Mounjaro patients and 18% of Ozempic patients lost at least 15% of their starting weight.

The researchers didn’t examine the biological mechanisms of the two drugs, but study leader Tricia Rodriguez, a principal applied scientist with Truveta Research, said Mounjaro may have been more effective because it works two ways instead of just one.

Dr. Ken Fujioka, an endocrinologist who leads the Scripps Clinic Nutrition and Metabolic Research Center in San Diego and who was not involved in the study, noted that the FDA approved a higher dose of Ozempic in March 2022 but that many doctors were not aware of that during the study period. With proper dosing, he said, the patients on Ozempic would have seen better results.

“I do believe that Mounjaro does give more weight loss than Ozempic,” said Fujioka, who has received consulting and speaking fees from the makers of both drugs. “I am just not sure how much.”

Providing GLP-1 drugs to 19.7 million Medicare beneficiaries with obesity would cost $268 billion a year, researchers estimate in a recent study.

The big gap in effectiveness wasn’t accompanied by a measurable difference in the rate of moderate or severe side effects like bowel obstructions and pancreatitis, which were rare for patients in both groups. The researchers didn’t compare the risk of milder problems like nausea and vomiting because people wouldn’t necessarily report them to their doctors, Rodriguez said.

Regardless of which drug they took, patients with Type 2 diabetes lost less weight than patients without the disease, the researchers found.

That might be explained by the facts that certain diabetes treatments can cause weight gain, and that some patients eat more throughout the day to keep their blood sugar from getting too low, Freeby said.

DNA probably is a factor, Fujioka added. “Individuals that have the genetics to become diabetics probably have the genetics to gain weight and hold onto it better,” he said.

It’s also possible that people who sought prescriptions for Ozempic or Mounjaro with the goal of slimming down were more motivated to keep taking the drug even if it was expensive or caused uncomfortable side effects, or that they were more likely to adopt other behaviors that promote weight loss, Rodriguez said.

Figuring this out is “a crucial topic for future research,” she said.

Researchers at McAfee have found a near tripling in the number of phishing attempts and malicious websites tied to Ozempic and other costly weight-loss drugs.

People currently taking Ozempic likely have a more pressing question on their minds: Should I switch to Mounjaro?

Dr. Nick Stucky, an infectious disease physician at Providence Portland Medical Center and the study’s senior author, said the results alone should not cause patients to stop taking a drug that is working for them. The risk of side effects, insurance coverage and drug availability are things to consider as well.

“While tirzepatide was significantly more effective than semaglutide, patients on both medications experienced substantial weight loss,” said Stucky, who is also Truveta’s vice president of research.

Freeby seconded that opinion.

“If someone is doing well with a medication, why rock the boat?” he said.

Freeby added that Ozempic (and its sister medication Wegovy, which is FDA-approved specifically for weight loss) has at least one advantage over Mounjaro (and Zepbound, its weight-loss counterpart): In clinical trials, Ozempic has been shown to reduce the risk of heart attacks, strokes and other cardiovascular problems as well as kidney failure.

“At this point, we don’t have a lot of data on Mounjaro when it comes to secondary outcomes,” he said.