Drug can amplify naloxone’s effect and reduce opioid withdrawals, study shows

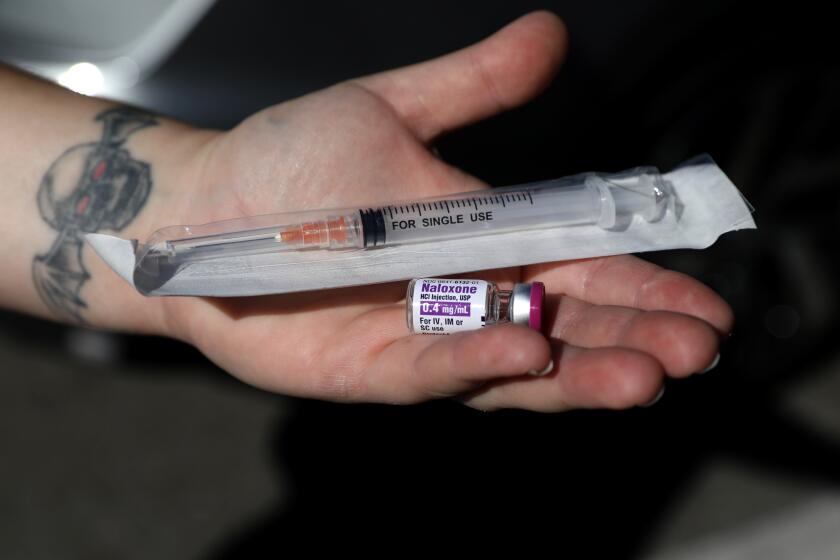

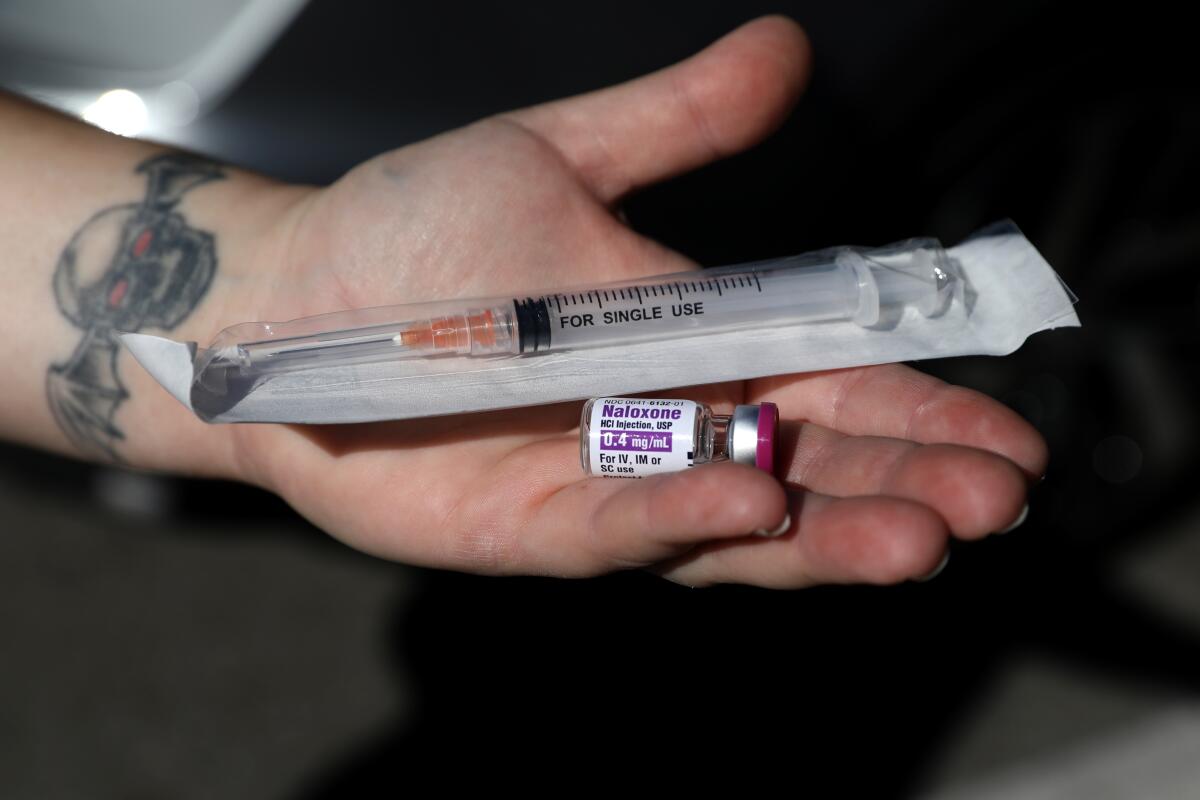

Naloxone has long been hailed as a life-saving drug in the face of the opioid epidemic. But its capacity to save someone from an overdose can be limited by the potency of the opioid — a person revived by naloxone can still overdose once it wears off.

Stanford researchers have found a companion drug that can enhance naloxone’s effect — and reduce withdrawal symptoms. Their research on mice, led by Stanford University postdoctoral scholar Evan O’Brien, was published today in Nature.

Typically, overdose deaths occur when opioids bind to the part of the brain that controls breathing, slowing it to a stop. Naloxone reverses overdoses by kicking opioids off pain receptors and allowing normal breathing to resume.

However, it is only able to occupy pain receptors for 30 to 90 minutes. For more potent opioids, such as fentanyl, that may not be long enough.

To determine how the naloxone companion drug, which researchers are calling compound 368, might boost naloxone’s effectiveness, researchers conducted an experiment on pain tolerance in mice, said Jay McLaughlin, a professor of pharmacology at the University of Florida. How quickly would mice pull their tails out of hot water, depending on which combination of opioids and treatments they were given?

Death rate from overdoses stopped rising among unhoused people in the county in 2022 — the year L.A. County was stepping up life-saving efforts, a new report found.

Mice that were injected with only morphine did not respond to the hot water — given their dulled pain receptors. Mice given morphine and naloxone pulled their tails out within seconds. No surprises yet.

When the dosage of naloxone was reduced and compound 368 was added, the compound was found to amplify naloxone’s effects, as if a regular dose was used. When used on its own, the compound had no effect, indicating that it is only helpful in increasing the potency of naloxone.

What researchers did not expect, however, was that the compound reduced withdrawal symptoms.

McLaughlin said withdrawal is one reason that people who have become physically dependent on opioids may avoid naloxone.

“Opioid withdrawal will not kill you, but I have talked to a number of people who have gone through it, and they have all said the same thing: ... ‘I wished I was dead,’” McLaughlin said. “It has a massive range of nasty, horrible effects.”

The idea that the compound could amplify naloxone’s effect at a lower dosage, while limiting withdrawal symptoms, indicates that it may be a “new therapeutic approach” to overdose response, McLaughlin said.

The research team said their next step is to tweak the compound and dosage so that the effects of naloxone last long enough to reverse overdoses of more potent drugs.

Though the compound is not yet ready for human trials, the researchers chose to release their findings in the hope that their peers can double check and improve upon their work, said Susruta Majumdar, another senior author and a professor of anesthesiology at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

“We may not be able to get that drug into the clinic, but somebody else may,” Majumdar said. He added: “Let them win the race.”

The state and L.A. County have worked hard to make Naloxone more widely available. One of the hurdles, though, has been the price of the inhalable version, Narcan.