Inside a clinic wedged next to a smoke shop in a South Los Angeles strip mall, Dr. Mohamad Yaghi operated on a 28-year-old woman who had traveled from Las Vegas to have fat trimmed from her arms and stomach. Yaghi had been offering liposuction for roughly seven years when he started making incisions that day in October 2020, but he was trained as a pediatrician, according to a formal accusation later filed by state regulators.

When the woman stopped breathing less than an hour into the surgery at La Clinica de Los Angeles, paramedics were summoned, according to the accusation. The mother of four died days later at Good Samaritan Hospital, unable to recover from the loss of oxygen to her brain.

Across the country, physicians from a range of specialties have ventured into the lucrative world of cosmetic surgery. Some have branched out with little or no surgical training.

Although rules differ from state to state, licensed physicians in the U.S. generally aren’t required to stick to practicing in the fields they studied during their medical education.

In California, “you could be trained in pediatrics, and then, if you have the cojones, you could be doing surgery,” said Dr. Michael S. Wong, former president of the California Society of Plastic Surgeons.

The L.A. practice where Yaghi worked was initially a family medicine clinic with an emphasis on pediatrics, according to the accusation by the Medical Board of California. He began offering “aesthetic services” around 2009, starting with sclerotherapy to treat unsightly veins and working his way up to breast augmentation, regulators said.

The state investigation into the woman’s death faulted him for alleged violations such as proceeding with surgery that involved sedation when he knew — or should have known — that the patient had recently consumed food or water, which increases the risk of food getting into the lungs.

Performing an elective surgery on a patient with “uncontrolled” diabetes was also “an extreme departure from the standard of care,” according to the accusation. The California Medical Board accused Yaghi of incompetence, gross negligence and other failures, prompting him to surrender his license earlier this year.

“There’s this misconception that cosmetic or aesthetic surgery is easy — and it’s not.”

— Dr. Melinda Haws, president of the Aesthetic Society

Yaghi had been drawn to cosmetic procedures “to expand his knowledge base and provide further access to patient care for his patients,” according to a statement provided by his attorney, who added that “cosmetic procedures always remained a minority part of his practice.”

Months after the death, Yaghi wrote a refund check for $6,500, according to the state accusation. The woman’s family later sued for malpractice and reached a settlement last year.

“Dr. Yaghi does regret the consequences of expanding his practice,” his attorney said.

Critics say preventing such tragedies has been difficult because state regulators across the U.S. give wide latitude to doctors to perform medical procedures once they are licensed.

In California, licensed physicians may “practice in any area of medicine, if they do so in a competent manner that complies with the law,” the medical board said. Besides checking that physicians meet periodic requirements for continuing education, the board weighs whether licensed doctors are “sufficiently trained” after receiving a complaint, it said.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

California has sometimes barred physicians from performing cosmetic surgery, but “it’s always after the fact” — when someone already has been harmed — said Dr. Debra Johnson, former president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. The grim joke, she said, has been: “You can do whatever you want until you kill somebody.”

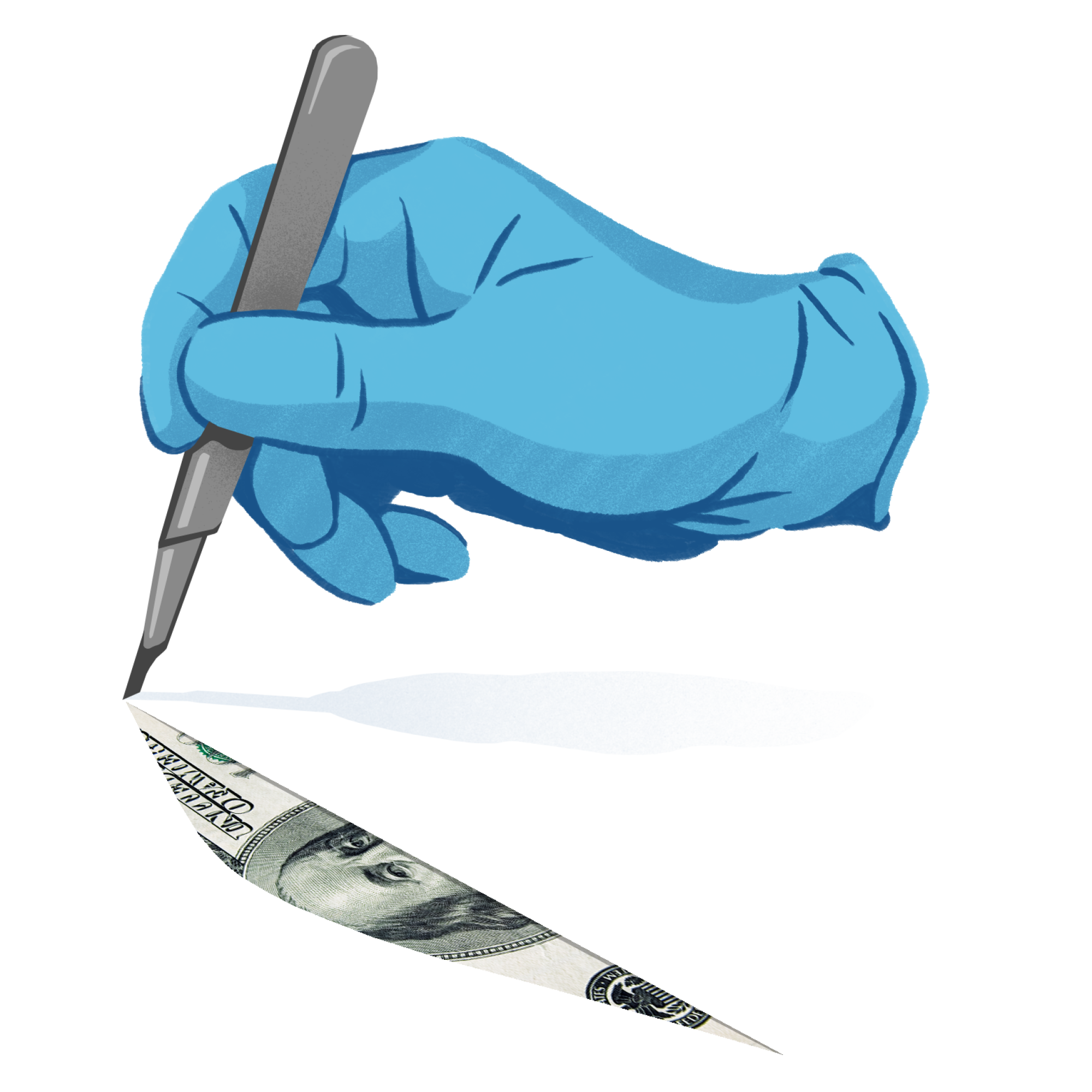

Experts say cosmetic surgery is particularly likely to draw physicians from other medical fields for several reasons: It happens outside of hospitals, patients usually pay out of pocket, and it can be lucrative.

Doctors seeking admitting privileges at a hospital must undergo a vetting process that allows the facility to check their training. But physicians performing aesthetic procedures in their own offices may avoid that.

In addition, health insurers can verify that physicians are qualified to perform the procedure for which they want to be reimbursed, said Mary Ellen Grant, a spokesperson for the California Assn. of Health Plans. But when cosmetic work isn’t considered medically necessary, the patient usually pays upfront, and the insurance company never gets involved.

“Our business is 99.9% cash,” said Dr. Jeffrey Swetnam, president of the American Board of Cosmetic Surgery.

Patient safety advocates say the earning potential is a draw for inadequately trained physicians. The North American market for cosmetic surgery in 2023 was estimated to exceed $18 billion, according to a Fortune Business Insights report.

“We need better standards,” said Carmen Balber, executive director of the advocacy group Consumer Watchdog. “Patients have the right to know that their doctor has the qualifications to do what they’re promising.”

A nationwide study of doctors marketing themselves as cosmetic surgeons found that 12% were practicing outside their scope of expertise. Among them were gynecologists, urologists and anesthesiologists; one practitioner wasn’t a doctor at all but a phlebotomist, trained to draw blood.

As a plastic surgeon, “I shouldn’t be delivering babies, right? ... I’m not trained in that. Yet there are people who are gynecologists who do liposuction — and it’s a real surgery,” said Dr. Melinda Haws, president of the Aesthetic Society.

Haws speculated that the industry may have become “victims of our own good press,” because the public has seen healthy patients faring well after outpatient procedures. “There’s this misconception that cosmetic or aesthetic surgery is easy — and it’s not.”

“It’s critical that patients be educated and know what they’re getting.”

— Dr. Jeffrey Swetnam, president of the American Board of Cosmetic Surgery

The emergency department at Loma Linda University Medical Center typically sees one or two patients a week who have a “major complication” from cosmetic surgery done by someone who is not a plastic surgeon, said Dr. Subhas Gupta, chair of plastic surgery at Loma Linda University Health. Common complications include infections and wounds not being properly closed, he said.

Patients may be unaware that a doctor can do such procedures without surgical training. Researchers in Tennessee who interviewed two dozen patients found that none knew that any licensed physician can offer aesthetic surgery — and almost all were uncomfortable with that fact.

“The cosmetic world is kind of the Wild West,” Swetnam said. “It’s critical that patients be educated and know what they’re getting.”

California does require outpatient facilities where physicians are using enough anesthesia to put patients at risk to be accredited or otherwise vetted, which can lead to scrutiny of physician training.

For instance, the accreditation agency Quad A requires physicians to have relevant certification from an approved board and to practice only within the scope of their medical specialty, said Dr. Robert Singer, a plastic surgeon who used to chair the agency board. If someone who trained solely as an ear, nose and throat doctor wants to do liposuction, “they would not be able to do that in our facilities.”

But such safeguards can be sidestepped: Some doctors may try to dodge California’s requirements for accreditation by using local anesthesia for surgical procedures that ought to be done with more sedation, Singer said.

Others have flouted the rules. Among the accusations lodged against Yaghi was that he gave intravenous sedation in a facility without proper accreditation — not only to the woman who died but to another patient, who suffered seizures and landed in an intensive care unit at L.A. County-USC Medical Center in 2018. State investigators only learned about that patient while investigating the 28-year-old woman’s death.

In Bakersfield, a 43-year-old woman died after getting liposuction and a tummy tuck from Dr. Sarwa Aldoori, who was trained in obstetrics and had completed a residency in family medicine, according to a state accusation.

Aldoori had taken “a few day courses in plastic surgery and a one-month course in liposuction and fat grafting” but “had no formal surgical training,” according to the California Medical Board’s accusation. Her facility lacked the accreditation needed for the administration of general anesthesia, regulators alleged.

Aldoori told The Times she had been a trauma surgeon in her country of origin and called the incident “pure bad luck,” saying the patient couldn’t have been saved regardless of where the surgery was performed.

Two years ago, the board put her on probation, barring her from participating in surgical procedures. She is facing the possible loss of her license after failing a neuropsychological evaluation, according to a petition filed by the state medical board.

The board said that over a decade, it has received more than 600 complaints alleging negligence in cosmetic surgery.

Some medical specialty groups have pushed to educate the public on how to assess physician qualifications. But many people don’t understand the steps involved in becoming a doctor, or the difference between a medical license and board certification, said Dr. Shirley Chen, a plastic surgery resident at Vanderbilt University Medical Center who has studied online advertising by doctors who perform cosmetic surgery.

A state-issued medical license “gives you a blanket ability to practice any type of medicine,” Chen said, but the board of a specialty assesses whether a doctor is skilled in that field. One study of lawsuits involving liposuction found that nearly half the defendants were not certified by any board approved by the American Board of Medical Specialties.

Adding to patients’ confusion is that “there’s a lot of different boards out there, and not all boards mean the same thing,” Chen said.

More parents are choosing to delay childhood vaccinations, such as the MMR vaccine. Doctors worry toddlers remain vulnerable as measles spreads.

In California, physicians have sparred over who can legally advertise themselves as “board-certified” in their specialty. California permits that for doctors certified by the American Board of Plastic Surgery — which requires U.S.-trained physicians to complete six to eight years of surgical training, including at least three years of plastic surgery residency — but not the American Board of Cosmetic Surgery, which mandates at least one year of fellowship training in cosmetic surgery after completing a residency in one of several approved fields.

The cosmetic surgery board asked the Medical Board of California to allow physicians who had met its requirements to advertise themselves as “board-certified.” Plastic surgery groups objected, arguing that the training requirements did not measure up. The proposal was unanimously rejected in 2018.

The American Board of Cosmetic Surgery decried the decision, calling it a turf battle aimed at limiting competition rather than protecting patients.

Yaghi and other California doctors who faced discipline named in this article are not American Board of Cosmetic Surgery diplomates. Nor were they certified by the American Board of Plastic Surgery.

For the record:

5:56 p.m. April 5, 2024This story has been updated to note that the California doctors who faced discipline named in the article are not diplomates of the American Board of Cosmetic Surgery. Nor were they certified by the American Board of Plastic Surgery.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Another wrinkle is that doctors offering cosmetic surgery may indeed be board-certified, but not in the kinds of procedures they are doing. A physician who did liposuction and breast augmentation procedures in Elk Grove, Calif., advertised himself as “board-certified,” but his certification was in internal medicine, not plastic surgery, according to the accusation filed by the medical board.

Dr. Mahmoud Khattab surrendered his license three years ago after being accused of violations involving nearly a dozen patients, including performing surgery in an unsafe environment, mismanaging burn injuries and engaging in “misleading advertising” of his board certification.

Khattab’s attorney said in a statement that his client trained abroad in general surgery and “took many courses in cosmetic procedures and surgery, but not a formal fellowship program.” However, “he has come to understand and believe that more invasive cosmetic surgical procedures should be performed by those with extensive surgical training in those procedures.”

Johnson said the California Society of Plastic Surgeons is exploring the idea of legislation that would bar doctors from performing outpatient surgery unless they have surgical training that was approved by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, which sets standards for residency and fellowship programs.

“If we can get the Legislature to agree that only surgeons should be doing surgery,” Johnson said, “I think that will go a long way.”