A Caltech Nobel laureate celebrates his 100th birthday. Then he gets back to work

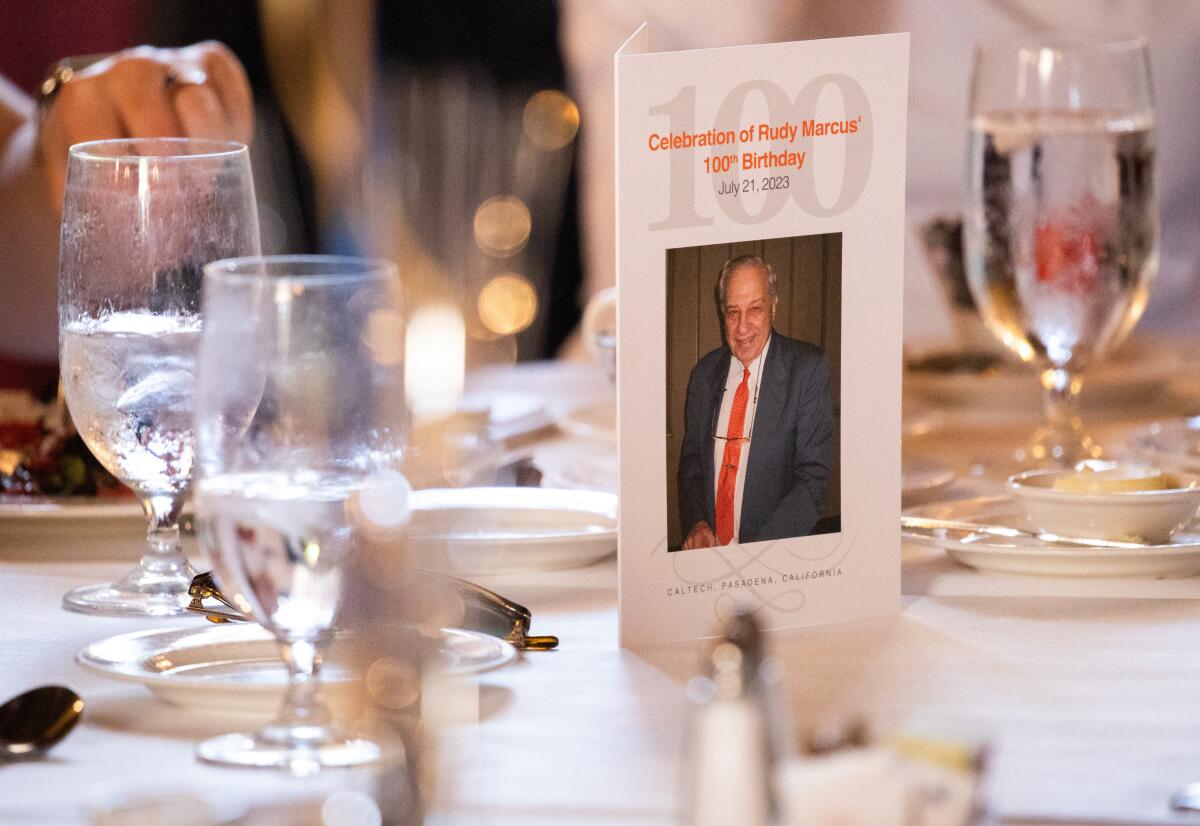

Say you wake up on the morning of your 100th birthday, having achieved the pinnacle of recognition in your chosen field and the warm esteem of family, friends and colleagues. How would you celebrate the day ahead?

“Work,” quipped Caltech chemistry professor Rudy Marcus at a lunch in honor of his centenary Friday.

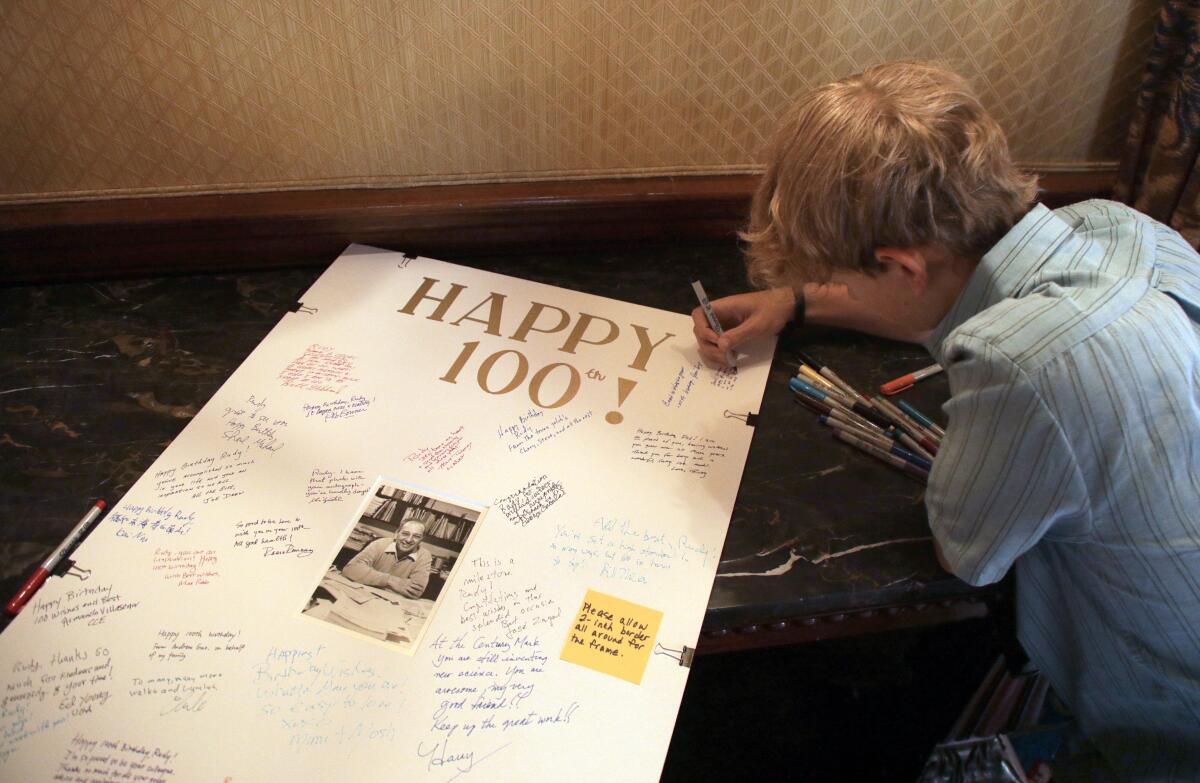

But the university where he’s been on the faculty for 45 years had other plans, so the Nobel laureate good-naturedly agreed to a symposium in his honor.

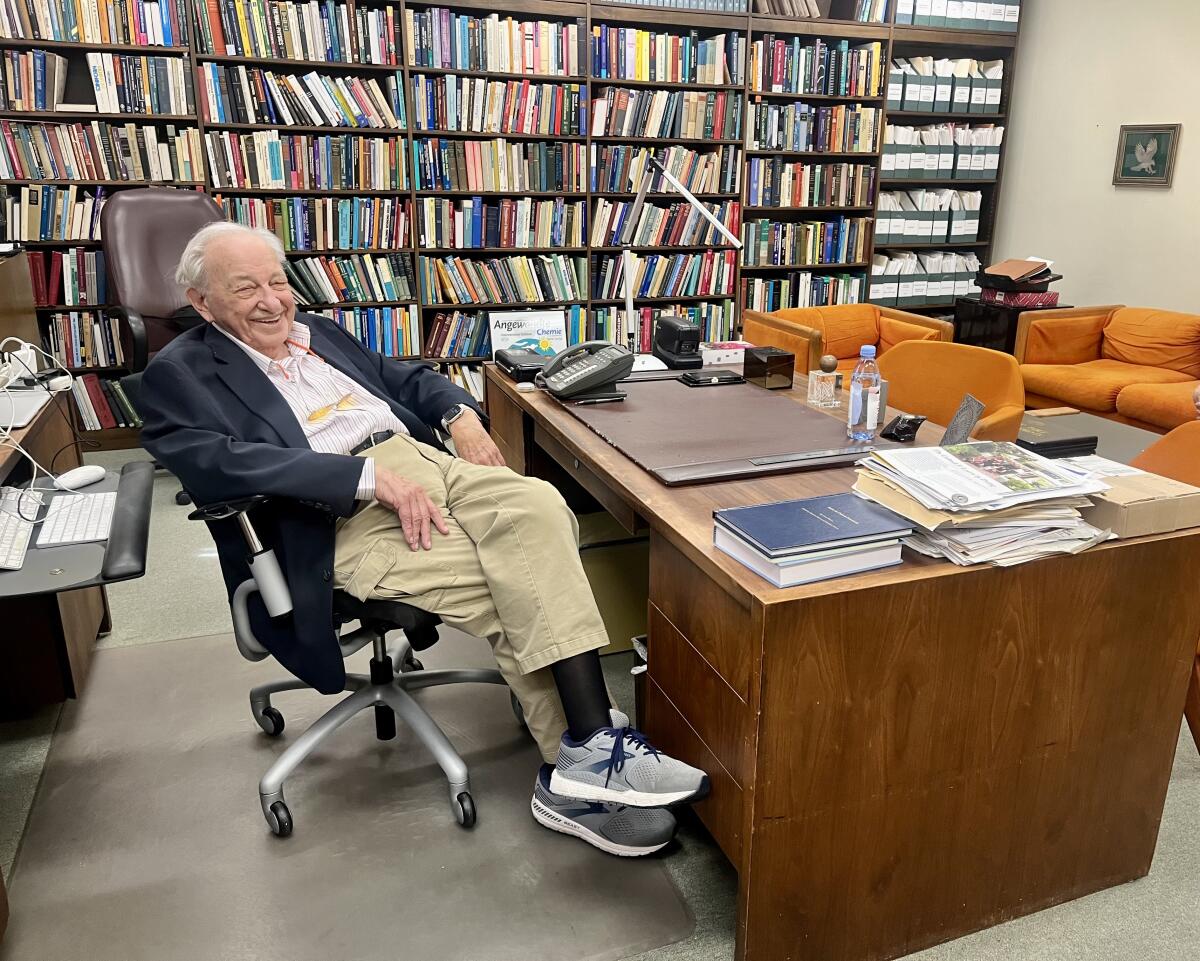

Generations of Marcus’ colleagues and former students gathered at the Athenaeum, Caltech’s faculty club, to celebrate a scientist who still reports to the book-lined office he has occupied on the Pasadena campus since 1978, and whose inquisitiveness and generous spirit remain undimmed.

“He’s an excellent example of what it is to be a scientist: the curiosity, the energy, the enthusiasm and the excitement for figuring things out,” said Stephen Klippenstein, a former doctoral student of Marcus’ who is now a theoretical chemist at Argonne National Laboratory.

“I don’t think I’ve ever heard him say a harsh word to anyone,” Klippenstein added, echoing others who described Marcus as a role model both in and out of the lab. “He leads by example: Work hard and solve hard problems.”

As a theoretical chemist, Marcus works with concepts rather than laboratory apparatus. He received his Nobel Prize in 1992 for work on electron transfer reactions, a deceptively simple theory describing how electrons move between molecules in chemical reactions without breaking chemical bonds.

While experimental chemists produce compelling new results in the lab, Marcus seeks the elegant architecture that undergirds their findings.

It’s an intellectual challenge that keeps him eager to return to his desk as his 11th decade begins. If anything, he said, his workload feels even more pressing as the sheer number of intriguing experiments grows.

“There are all sorts of developments in the laboratory and all sorts of new techniques that have been produced,” he said Friday as well-wishers milled around his table at a pre-symposium lunch. “I have plenty of work to do, more than I can comfortably handle.”

Marcus still publishes several research papers per year. The Office of Naval Research just renewed a grant he’s had since the 1950s.

Age has demanded some concessions. He walked to work each day from his house near the Pasadena campus until he was 97, when the COVID-19 pandemic forced him to stop.

He hung up his skis at the age of 90, not because he couldn’t physically continue but because it seemed unwise to do so.

“I’d love to ski, but I’d love not to break any bones,” he said. “Once people get hospitalized, for some that’s the beginning of the end, and there’s too much to do yet.”

A Caltech professor won the 1992 Nobel Prize in chemistry on Wednesday for theories that help explain how living things store energy, but first word of the $1.2-million award went to his answering machine.

Marcus’ work ethic is legendary, colleagues and family members said.

When his eldest son, Alan Marcus, a cultural historian and professor at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, decided to shift to part-time work as his 65th birthday approached, “Dad said, ‘You’re such a slacker,’ ” the younger Marcus recalled with a laugh.

Marcus was married to Laura Hearne from 1949 until her death from multiple myeloma in 2003. Their sons Alan, Kenneth and Raymond all obtained doctoral degrees in history.

Marcus continued to teach until the age of 95, when he decided “enough is enough.”

“They should really have somebody who really knows something,” he said.

As a teacher, Marcus “has this uncanny ability to reduce very complex problems into simple essentials,” said Caltech chemist Zhen-Gang Wang. “The electron transfer theory” — his Nobel Prize-winning work — “is a great example of that.”

Marcus was at an electrochemistry conference when the call came in from Stockholm in 1992. At a hastily called news conference at the Toronto hotel where he was staying, the professor demurred when asked about the newfound fame that comes with being a Nobel laureate.

“I don’t know that I want to attract more attention to my work,” a bemused Marcus told reporters. “I just want more time to get it done.”

He got his wish. His colleagues couldn’t have foreseen the sheer longevity of his tenure when he arrived at Caltech during the Carter administration, “but the Nobel Prize quality, yes,” said John D. Baldeschwieler, a retired professor emeritus of chemistry who was chair of the department at the time of Marcus’ hiring.

Marcus was born in 1923 in Montreal, the much-loved only child of Esther and Myer Marcus. His mother in particular instilled a love of learning, in part motivated by the fact that her own family lacked the money to continue her education beyond grade school.

“She told me that when I was a baby and she used to wheel me in a carriage around McGill, she told me that I would go there,” he said in an oral history collected by Caltech in 1993. (She was right: He earned both his bachelor’s degree and doctorate at the prestigious Montreal university.)

He was drawn to puzzles as a child, and has often described his approach to science as a decades-long continuation of the childlike pleasure of teasing a solution from once-scattered parts.

“The main thing is finding something that you enjoy doing, that preferably doesn’t harm others, and that tests whatever aptitude one has, that tests one’s ingenuity,” he said. “It’s almost like a kind of a game. You against nature.”