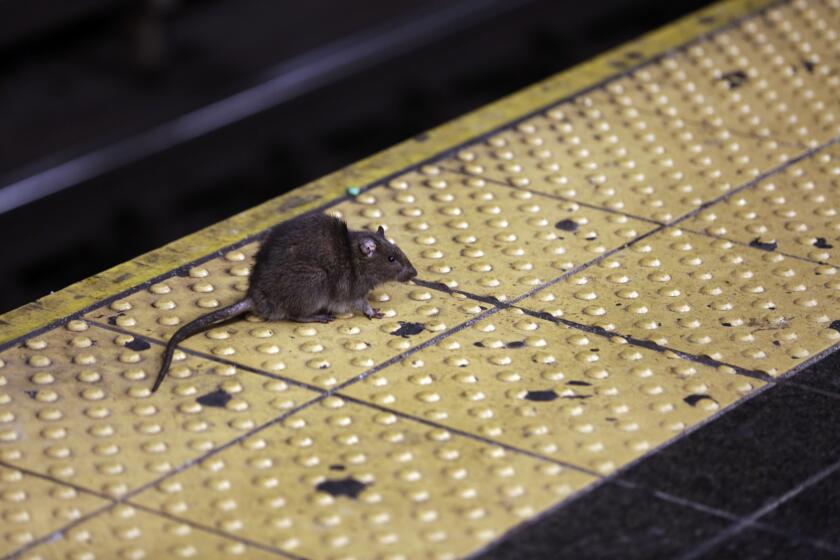

The coronavirus has infected New York City’s rats. Why that’s bad news for people

Rats, whose populations in cities exploded during the pandemic, have now joined the list of wildlife believed to be capable of catching and transmitting the virus that causes COVID-19, new research finds.

In a study published Thursday in the journal mBio, researchers showed that rats — like dogs, cats, hamsters, ferrets and humans’ other close cohabitants — can pick up the pandemic virus from their environment.

They don’t appear to get very sick; none of the wild rats deliberately infected in a lab lost weight or died as a result. But when the rats were exposed to the Alpha, Delta and Omicron variants of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, researchers found evidence of robust viral replication in the animals’ noses, mouths, throats and lungs.

In addition, a detailed examination of 79 so-called brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) collected in and around the sewers of New York City turned up telltale signs that 13 had been exposed to the coronavirus and developed an immune response. Indeed, PCR testing of the rats’ respiratory tissue suggested that four of the 79 rats had active infections when they were euthanized.

The deepest fears of some New Yorkers are crawling to the surface as the metropolis continues its recovery from the pandemic.

The research was conducted by scientists from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and the University of Missouri. It brings to 11 the number of known wildlife “reservoirs” for the pandemic virus, which has been shown to infect deer, mink, otters, gorillas, lions and tigers as well.

The virus’ presence in all those species not only ensures that the coronavirus will never disappear from our midst. It also raises the possibility that, as the ever-changing virus adapts to new and very different hosts, it will evolve in ways that make it unrecognizable to humans who thought they had become immune to it.

Brown rats, also known as Norway rats, have coexisted with humans for thousands of years and are prolific transmitters of human diseases. Exposure to their feces, urine or saliva is known to spread hantavirus, leptospirosis, lymphocytic choriomeningitis, tularemia and salmonella.

As the pandemic winds down, the new findings suggest a frightening scenario in which wild rats, whose populations in U.S. cities have seen explosive growth in the last three years, could become not only a vector for reinfection of humans but also a source of new variants that evade our protection from vaccines or past infections.

If the coronavirus recombines with another virus carried by rats, or if it simply evolves to spread more readily within that population, the result could be a novel pathogen capable of rebooting the pandemic, the study authors said.

The findings underscore “the need for further monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 in rat populations for potential ... transmission to humans,” they wrote.

Other researchers have suggested that biological differences between humans and wild rats have made this wildlife population particularly fertile ground for introducing mutations into the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The authors cite a study that suggests that rodents may have played a role in the evolution of the Omicron variant. This surmise is grounded in the fact that some of Omicron’s mutations improved the virus’ ability to latch on to rodent cells even more than they improved its attachment to human cells. But co-author Henry Wan of the University of Missouri School of Medicine acknowledged “this is still just speculation.”

Are there really 8 million rats living among the 8 million humans of New York City?

There remains the challenge of knowing whether and how infected rats could transmit the coronavirus to humans.

The study authors demonstrated that in laboratory conditions, rats infected with a related coronavirus developed infections and shed virus. And, like humans, these rats could be infected repeatedly.

The finding that these infected rats are capable of spreading their germs raises the disconcerting prospect that as free-range rats scurry across surfaces touched by humans, their noses could deposit respiratory secretions that deliver the virus to people. While aerosol transmission has been the primary means by which the coronavirus has spread among humans, acquiring the virus through touch is a concern as well.