With monkeypox in the news, why are people talking about smallpox?

Why are we talking about smallpox again?

The virus is estimated to have killed more than 300 million people in the 20th century. But by 1980, thanks to a successful vaccination campaign, it was eradicated. No one today receives routine childhood vaccinations for smallpox, because you can’t catch it anymore.

But the disease is back in the public consciousness because of monkeypox. In fact, monkeypox was discovered during the global smallpox vaccination campaign. And the global eradication of smallpox may have created an opening for monkeypox, said Peter Hotez, co-director of the Center for Vaccine Development at Texas Children’s Hospital and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine

“Monkeypox is believed to have become more prevalent after we stopped vaccinating populations against smallpox,” he said. “We pretty much slowed or halted smallpox vaccine programs” — the last routine shots were given in the 1970s in the U.S. — “and that was actually enabling for monkeypox to emerge among human populations, because immunity was wearing off.”

The first human case of monkeypox was recorded in 1970.

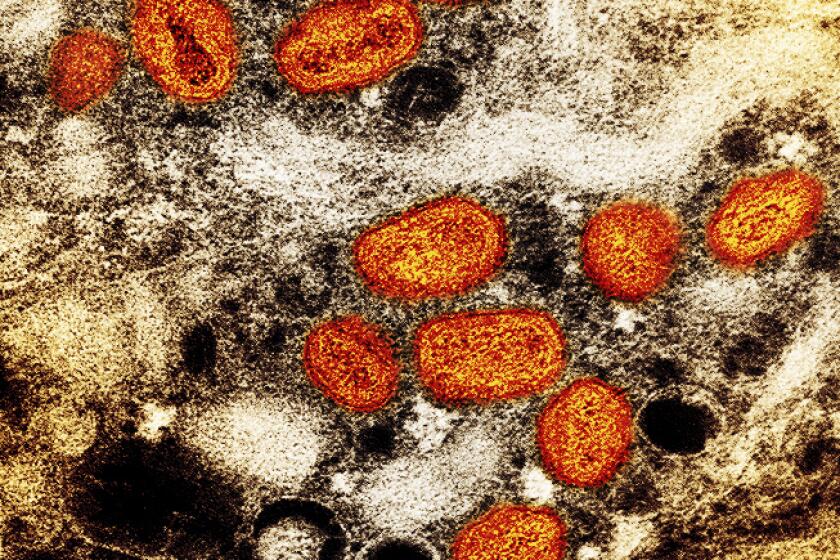

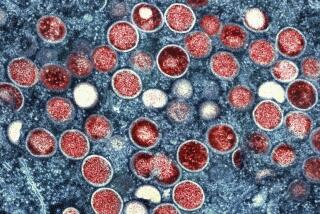

Both smallpox and monkeypox are caused by orthopoxviruses. The symptoms are similar, though monkeypox is rarely fatal. The diseases are so similar, in fact, that the same vaccine is used for both: Jynneos. So the monkeypox vaccine is the smallpox vaccine; they are not different shots.

What if you were vaccinated against smallpox pre-1980? Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Assn., said you would likely have some degree of protection from monkeypox, but you should still get the Jynneos vaccine if you’re exposed or are otherwise eligible.

“Unless you were recently vaccinated for smallpox, like the last two to three years, most likely you probably want to go ahead and get vaccinated if you’re exposed,” he said.

Los Angeles County’s monkeypox vaccination effort will initially focus on getting first shots into arms over administering both doses.

With monkeypox cases rising in the United States, are we all going to need to get vaccinated for smallpox? Right now, it doesn’t seem like that will be necessary.

It’s alarming to see another infectious disease gain a foothold while we’re still attempting to fend off COVID-19. But COVID and monkeypox are very different, said Anne Rimoin, a professor of epidemiology at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health and a member of the World Health Organization’s emergency committee on monkeypox.

“I’ve been working on this virus for 20 years. It’s a virus that does not spread as easily as something like SARS-CoV-2. Its most efficient route of transmission is close, prolonged, skin-to-skin contact,” she said.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, was known as “the novel coronavirus” because we had never seen it prior to 2019. With monkeypox, “this is not a novel virus. This is a virus that we know,” Rimoin said.

You can already look at the data trajectories and see how different things are: The first U.S. case of monkeypox was confirmed on May 18. Cumulatively, we’ve had 7,083 cases, with 2,186 of those in the last seven days, and zero deaths. Four months after COVID-19 first appeared in the United States — late May 2020 — we were averaging more than 20,000 new cases and around 1,000 deaths every day.

“Monkeypox can spread in a variety of ways. It can spread through contaminated objects, respiratory secretions, but really that’s not what we’re seeing as the primary mode of transmission in this outbreak. What we’re seeing is the vast majority of cases are from prolonged skin-to-skin contact, generally in the context of sex,” Rimoin said.

For decades monkeypox was not known as a disease that spreads through sex. That has changed.

Right now, the disease “is really spreading through specific sexual and social networks,” Rimoin said. And outside of those communities — gay and bisexual men and transgender people — the risk of getting monkeypox right now “is fairly low,” Rimoin said.

You must be 18 or older and a gay or bisexual man or transgender person and meet at least one of the following criteria to be eligible for the vaccine:

- You have had multiple sex partners in the last 14 days, including (but not limited to) having sex in exchange for food, shelter or other goods or needs.

- You are on HIV PrEP medication.

- You’ve had anonymous sex or sex with multiple people within the last 21 days at a commercial sex venue or other venue.

- You’ve had high or intermediate exposure to monkeypox (the CDC has a list of what qualifies as exposure at those levels).

- You’ve attended an event or venue where there was a high risk of exposure via skin-to-skin or sexual contact with people with monkeypox.

- You are experiencing homelessness and engaging in high-risk behaviors.

- You’ve had gonorrhea or early syphilis in the last 12 months.

- You are in jail and have been identified as high-risk by clinical staff.

- You are severely immunocompromised — for instance, you are undergoing chemotherapy, are on high-dose steroids or other immunosuppressants or have advanced or uncontrolled HIV.

The Los Angeles Department of Public Health provides a link to register for appointments for a monkeypox vaccine for those who are eligible. The list closes when no more spots are available. The county has a newsletter that will send you an email when spots have opened.

If you think you have been exposed to monkeypox, contact your healthcare provider, call 211 or visit a public sexual health clinic.

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.