WHO to share vaccines to stop monkeypox amid inequity fears

LONDON — The World Health Organization said it’s creating a new vaccine-sharing mechanism to stop the outbreak of monkeypox in more than 30 countries beyond Africa. The move could result in the U.N. health agency distributing scarce vaccine doses to rich countries that can otherwise afford them.

To some health experts, the initiative potentially misses the opportunity to control monkeypox virus in the African countries where it’s infected people for decades, serving as another example of the inequity in vaccine distribution seen during the COVID-19 pandemic.

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said the agency is developing an initiative for “fair access” to vaccines and treatments that it hopes will be ready within weeks. The mechanism was proposed shortly after Britain, Canada, France, Germany, the U.S. and other countries reported hundreds of monkeypox cases last month.

The WHO has described the outbreak as “unusual” and said the virus’ continuing spread was worrying enough to convene its expert committee next week to decide if monkeypox should be declared a global emergency.

Vaccines for smallpox, a related disease, are thought to be about 85% effective against monkeypox. The WHO’s Europe director, Dr. Hans Kluge, said Wednesday that he was concerned by the scramble by some rich countries to buy more vaccines without talk of buying supplies for Africa.

The U.S. government is buying more monkeypox vaccine as a surprising international outbreak continues to grow.

Kluge urged governments “to approach monkeypox without repeating the mistakes of the pandemic.” Still, he did not discount the possibility that countries like Britain, which currently has the biggest outbreak beyond Africa, might receive vaccines through the WHO.

He said that the program was being created for all countries and that vaccines would largely be dispensed based on their epidemiological needs.

“Europe remains the epicenter of this escalating outbreak, with 25 countries reporting more than 1,500 cases, or 85% of the global total,” Kluge said.

Some African experts questioned why the U.N. health agency has never proposed using vaccines in central and West Africa, where the disease is endemic.

“The place to start any vaccination should be Africa and not elsewhere,” said Dr. Ahmed Ogwell, acting director of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He said the lack of any vaccines to counter monkeypox on the continent, where more than 1,500 suspected cases and 72 deaths have been reported this year, was a more critical concern than the clusters of mostly mild disease being reported in rich countries.

The resources needed to prevent monkeypox have long been available, just not to the Africans who have dealt with it for decades.

“This is an extension of the inequity that we saw during COVID,” said Dr. Ifeanyi Nsofor, a Nigerian infectious diseases physician and consultant at the communications agency Upswell. “We have had hundreds of monkeypox cases in Nigeria from 2017 until now and we’re just dealing with it on our own,” he said.

After the COVID-19 pandemic exploded in 2020, global health agencies rushed to set up COVAX, a U.N.-backed effort to distribute COVID-19 vaccines. But rich countries bought up most of the world’s supply, and the COVAX program missed multiple targets to share doses with the world’s poor.

To date, only about 17% of people in poorer countries have received a single dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Some experts fear the same thing could happen with monkeypox.

“Just like with COVID, there is no clear path for how poorer countries will be able to get vaccines,” said Brook Baker, a Northeastern University law professor who specializes in access to medicines.

He warned that as the WHO attempts to determine how many vaccine doses are available, rich countries that previously promised doses might not cooperate. “Rich countries will protect themselves while people in the global south die,” Baker predicted.

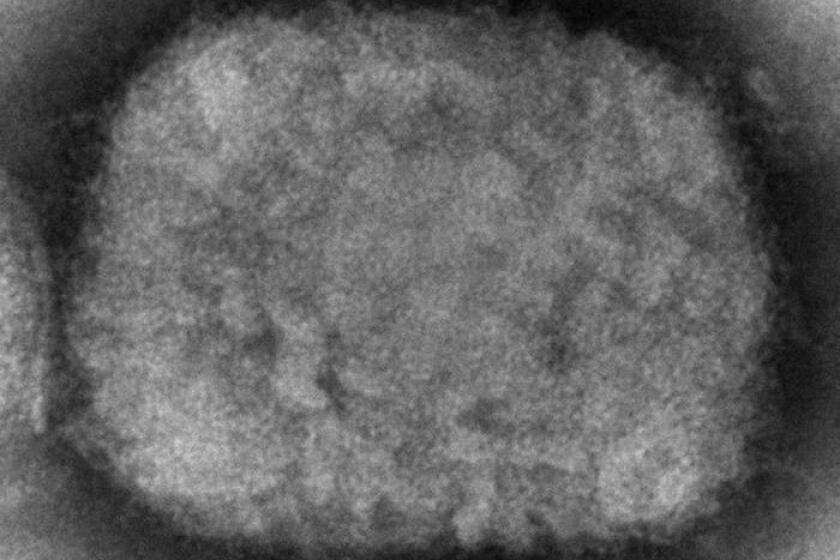

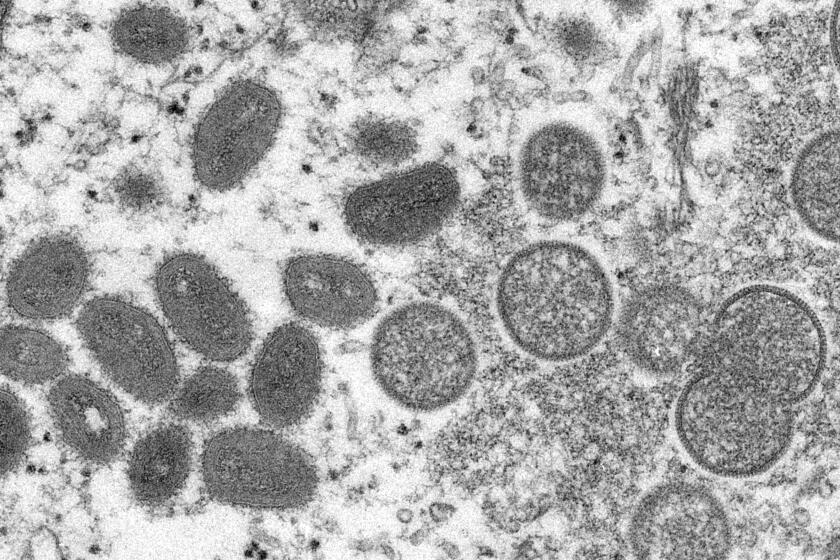

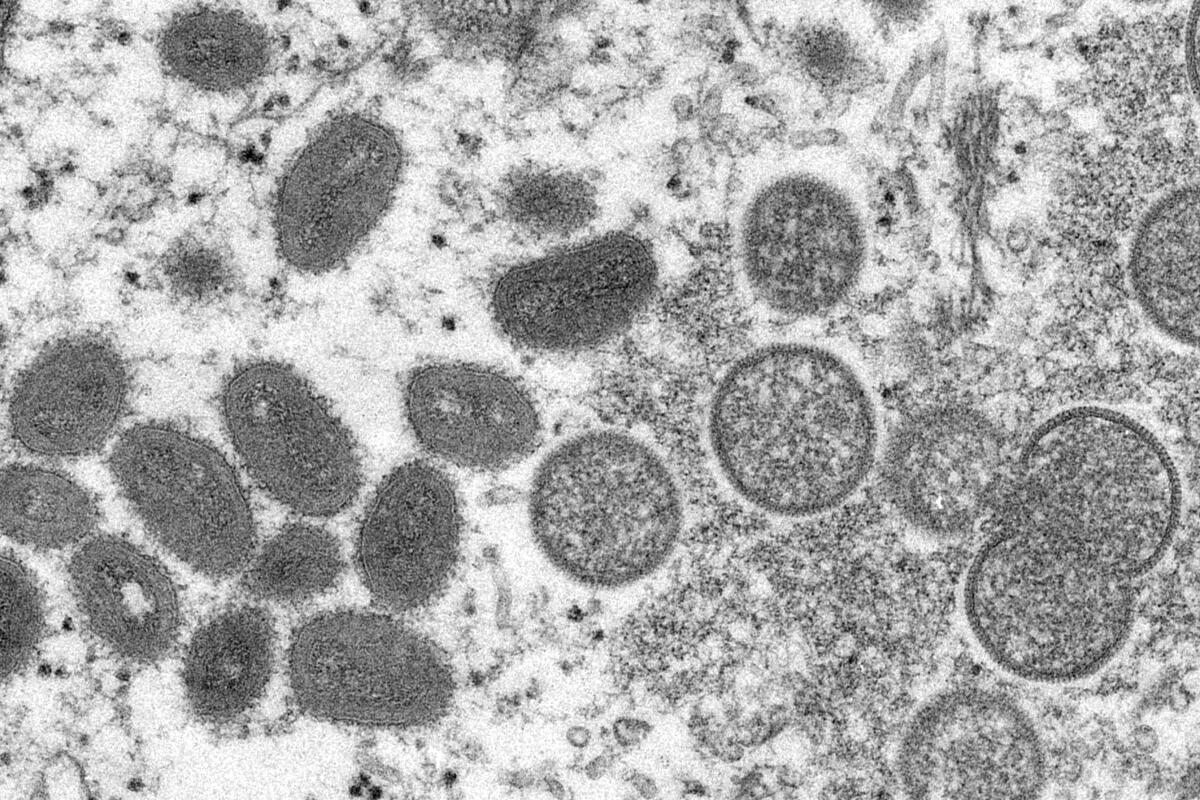

To the public, the monkeypox outbreak has echoes of the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. But scientists say it’s not the same at all.

On Monday, advocacy group Public Citizen sent a letter to the White House asking whether the Biden administration would release the 20 million smallpox vaccines the U.S. pledged in 2004 for the WHO’s use in the event of an emergency, like a biological attack.

Asked about the commitment, a senior U.S. official said the government was “exploring all options” to further their efforts to stop monkeypox within the U.S. and globally.

The official said the U.S. had returned more than 200,000 doses of a smallpox vaccine to the manufacturer so they would be available to others. The official declined to say if the U.S. considers the current monkeypox outbreak an emergency that warrants the release of the 20 million pledged vaccines.

According to the health data and analytics firm Airfinity, the U.S. has at least 1.4 million doses of vaccine and has ordered an additional 13 million. To date, the U.S. has reported 72 monkeypox cases.

Francois Balloux, an infectious diseases expert at University College London, said vaccination efforts in rich countries should prompt an overhaul of future monkeypox response strategies in Africa.

“It really should be a priority to vaccinate people in Africa, where there is a nastier strain that has actually killed people,” he said, adding that more monkeypox spillovers were likely in the future.

“Whatever vaccination happens in Europe, that is not going to solve the problem,” Balloux said.

Zeke Miller in Washington contributed to this report.