FDA halts use of antibody drugs that don’t work against Omicron

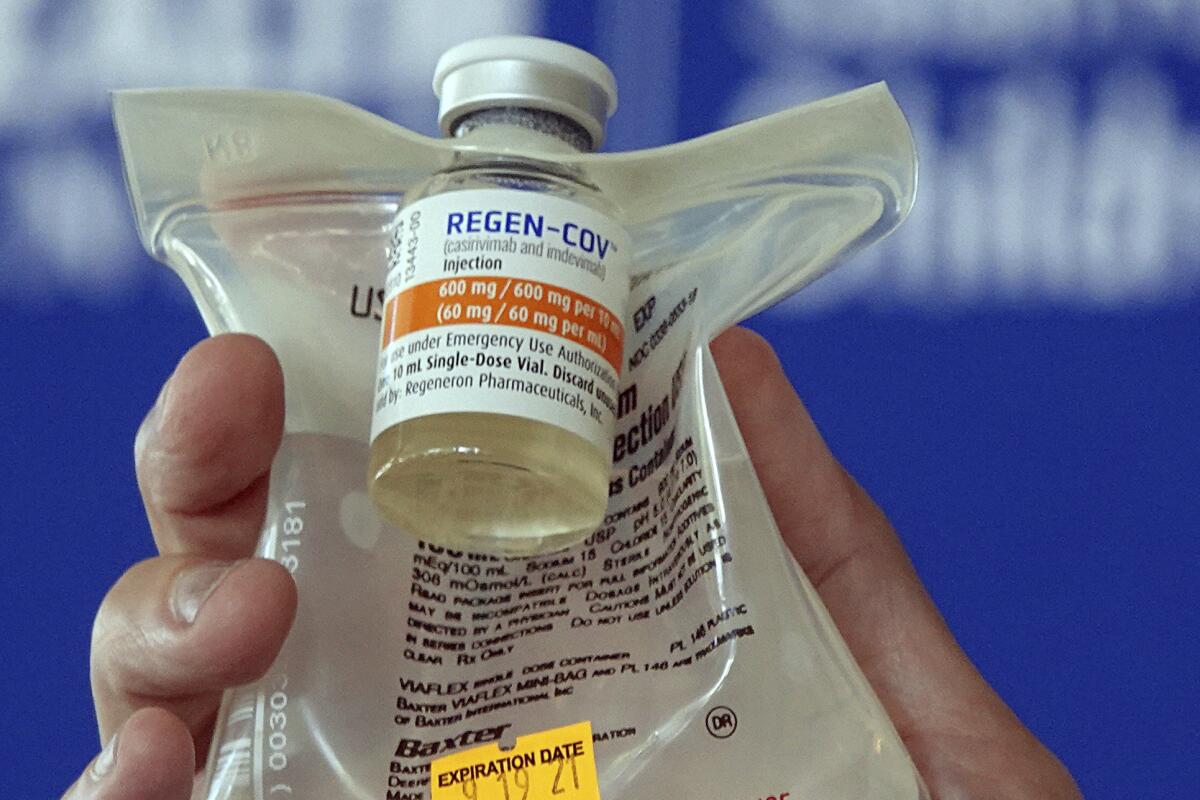

WASHINGTON — COVID-19 antibody drugs from Regeneron and Eli Lilly should no longer be used because they don’t work against the Omicron variant that now accounts for nearly all U.S. infections, U.S. health regulators said.

The Food and Drug Administration said Monday it was revoking emergency authorization for both drugs, which were purchased by the federal government and have been administered to millions of Americans with COVID-19. If the drugs prove effective against future variants, the FDA said, the agency could reauthorize their use.

The regulatory move was expected because both drugmakers had said the infusion drugs are less able to target Omicron because of its mutations. Still, the federal action could trigger pushback from some Republican governors who have continued promoting the drugs against the advice of health experts.

Omicron’s resistance to the two leading monoclonal antibody medicines has upended the treatment playbook for COVID-19 in recent weeks.

Doctors have alternate therapies to battle early COVID-19 cases, including two new antiviral pills from Pfizer and Merck, but both are in short supply. An antibody drug from GlaxoSmithKline that remains effective also is hard to get.

The drugs are laboratory-made versions of virus-blocking antibodies. They are intended to head off severe disease and death by supplying concentrated doses of one or two antibodies early in an infection. Then-President Trump received Regeneron’s antibody combination after he tested positive for the coronavirus in 2020.

Two brand-new COVID-19 pills that were supposed to be an important weapon against the pandemic in the U.S. are in short supply.

The FDA noted in its decision that Omicron accounts for more than 99% of U.S. infections, making it “highly unlikely” the antibodies would help people now seeking treatment. The agency said restricting their use would also eliminate unnecessary drug side effects, including allergic reactions.

The U.S. government temporarily stopped distributing the two drugs in late December, as Omicron was racing across the country to become the dominant variant. But officials resumed distribution after complaints from Republican governors, including Florida’s Ron DeSantis, who claimed that the drugs continued to help some Omicron patients.

DeSantis has heavily promoted antibody drugs as a signature part of his administration’s COVID-19 response, setting up infusion sites and lauding them at news conferences, while opposing vaccine mandates and other public health measures. Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has also launched state-sponsored infusion sites.

The drugs are not a substitute for vaccination and are generally reserved for people who are the most vulnerable, including seniors, transplant recipients and those with conditions such as heart disease and diabetes.

Since early January, the U.S. government has shipped enough doses of the two antibodies to treat more than 300,000 patients.

Governors in COVID-19 hotspots endorse experimental antibody treatments even as they downplay vaccination and other preventive measures.

Both Regeneron and Lilly previously announced they were developing new antibodies that target Omicron.

The move comes days after regulators broadened the use of remdesivir — the first drug approved for COVID-19 — to treat more patients.

On Friday, the FDA expanded the antiviral drug’s approval to include adults and children with early COVID-19 who face a high risk of ending up in the hospital. Remdesivir previously had been limited to hospitalized patients.

An influential panel of federal experts had already recommended using the infused drug to try to head off hospitalization. The same guidelines from the National Institutes of Health panel recommend against continued use of Lilly and Regeneron’s antibody drugs due to their reduced effectiveness against Omicron.

Still, many hospitals will face challenges in ramping up remdesivir treatments. The drug requires three consecutive IV infusions over three days, when used for nonhospitalized patients. That time-consuming process won’t be an option for many over-capacity hospitals facing staff shortages.

The FDA made its decision based on a 560-patient study that showed a nearly 90% reduction in hospitalizations when remdesivir is given within seven days of symptoms. The study predates the Omicron variant, but, like other antivirals, remdesivir is expected to maintain its performance against the latest variant.