U.S. gives final clearance to COVID-19 shots for kids 5 to 11

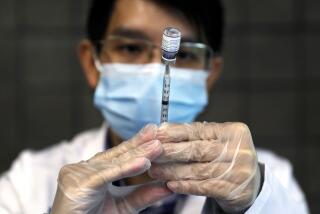

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Tuesday fired the starting gun on a campaign to inoculate the nation’s 28 million elementary-school-age children against COVID-19, recommending the broad use of kid-size doses of the vaccine made by Pfizer and BioNTech.

Shots into little arms are expected to begin this week. Pfizer already is shipping the first orders, featuring vials with distinctive orange caps, to states and pharmacies across the country.

Children between the ages of 5 and 11 will get two shots of vaccine — at one-third the dosage of shots for teens and adults — administered three weeks apart.

The CDC estimates that if the vaccine is widely used, 600,000 new coronavirus infections could be prevented between now and next March, and the current decline in new cases would accelerate.

Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the CDC director, said she was thrilled to extend the protection already enjoyed by 193 million Americans to a group whose lives have been upended by the 20-month pandemic.

“We know millions of parents are eager to get their children vaccinated,” Walensky said, adding that Tuesday will go down as “a monumental day in the course of the pandemic.”

The CDC’s recommendation applies universally to 5- to 11-year-olds, regardless of whether they’ve had a previous coronavirus infection or have an underlying medical condition that would put them at heightened risk for a serious case of COVID-19.

“As a mom, I encourage parents with questions to talk to their pediatrician, school nurse or local pharmacist to learn more about the vaccine and the importance of getting their children vaccinated,” Walensky said.

Why the question of vaccinating younger children against COVID-19 is more complicated than it would initially appear.

In California, the shots won’t be available until they are cleared in an additional review by the Western States Scientific Safety Review Workgroup, a coalition of public health experts from California, Nevada, Oregon and Washington. That might take an additional day to complete.

The CDC action came just hours after a panel of independent advisors issued a full-throated endorsement of the Pfizer-BioNTech’s vaccine for young children. After briefings that cast the vaccine as more than 90% effective in preventing COVID-19 in 5- to 11-year-olds, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted unanimously to recommend its use in all children in that age group.

“Based on our expertise and the information that we have, we’re all very enthusiastic,” said committee member Dr. Beth Bell, a professor of global health at the University of Washington.

After the votes were in, several members of the panel said they were eager to vaccinate youngsters in their families.

“I am going to take my child to get this,” said Veronica McNally, an attorney in West Bloomfield, Mich.

Dr. Sarah S. Long, a pediatric infectious-disease specialist at Drexel University, said the CDC action makes three of her nine grandchildren eligible for the vaccine. “By this time next week,” she noted, only her youngest grandchild will be unvaccinated.

“I am very supportive of this recommendation to its fullest extent as a ‘should’ — not a ‘maybe’ — for all children in this age group,” she added.

With the Delta variant surging, pediatricians and others are urging the FDA to move faster on COVID-19 vaccines for young children.

While children are much less likely than adults to become severely ill from a coronavirus infection, the pandemic has taken a heavy toll in this age group.

Theirs is the group most likely to be hospitalized with multisystem inflammatory syndrome, or MIS-C, in which the immune system responds to a SARS-CoV-2 infection by attacking healthy tissue. By early October, a total of 2,316 elementary-school-age kids in the U.S. had been hospitalized with MIS-C.

In all, 8,300 5- to 11-year-olds have been hospitalized with COVID-19, and 94 have died, according to the CDC. Roughly two-thirds of those who have landed in the hospital had some chronic health condition that put them at higher risk, such as asthma, obesity, heart problems or a compromised immune system. But one-third were entirely healthy before their bout with severe COVID-19.

And after a challenging school year marked by distance learning and modified classroom protocols, the summer saw things get worse. During a six-week period between late June and mid-August, as the Delta variant established itself across the U.S., COVID-19 hospitalizations among children and adolescents increased five-fold.

Even after mild infections, at least 7% of kids in this age group appear to suffer from long COVID — a mysterious condition in which symptoms — including cough, muscle aches, breathing problems and difficulty concentrating — can linger for months.

Children have played an important role in spreading the virus because they can carry and transmit it even when they do not have symptoms. The CDC estimates that if recent transmission trends continue, the vaccination of just nine children in this age group would prevent one new infection, and vaccinating 2,213 would spare one child from hospitalization.

With its vote Tuesday, the CDC’s advisory panel brushed aside concerns over cases of vaccine-related myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle. The condition is rare — it has been detected in 877 U.S. residents younger than 30 who received the Pfizer vaccine or a similar one made by Moderna, out of 86 million doses administered to people in that age group. The condition typically resolves with over-the-counter medications and rest, and none of the cases have been fatal.

Last week, however, concerns over how this rare vaccine side effect would affect a cohort of prepubescent children caused several advisors to the Food and Drug Administration to suggest that a more limited rollout of the vaccine would be a safer bet.

The closer we get to the end of the pandemic, the harder it is to justify the risk of a COVID-19 vaccine mandate for young children.

Pfizer’s clinical trials in 5- to 11-year-olds picked up plenty of cases of fatigue, headache and sore arms. But they did not detect signs of myocarditis — and were unlikely to do so, given their limited size.

Dr. Matthew Oster, a pediatric cardiologist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, told members of the CDC panel he believed myocarditis was “less likely” to be seen in younger children after vaccination than it has been in teens and young adults. “Classic” myocarditis, which sometimes develops in the wake of an infection, is rarely seen in prepubescent children, suggesting that hormonal changes may play a role, he said.

Irrespective of a patient’s age or gender, Oster added, “getting COVID is much riskier to the heart” than getting vaccinated to prevent it. Asked whether the benefits of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine outweigh its risks for young children, his answer was unambiguous.

“In my opinion, yes,” Oster said.

As the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine begins to roll into doctors’ offices and pharmacies, monitoring systems set up by the CDC and FDA will scour medical records and hotline reports to watch for any uptick in myocarditis among newly vaccinated kids. Several CDC advisors said they were reassured by experts’ evolving view of myocarditis, as well as the federal government’s vigilance in tracking it.

“We do understand that people have legitimate concerns, and they have lots of questions,” Bell said. She encouraged those with lingering doubts to discuss the issues with their pediatricians or other trusted advisors and “do what they need to do to feel comfortable with their decisions.”

In a survey conducted in September for the CDC, 35% of parents of 5- to 11-year-olds said they would “definitely” get their child vaccinated once the shots were available, and 26% said they would “probably” do so.

Among parents who were unsure, 45% expressed concerns about long-term side effects, 28% were worried about cardiac side effects in particular, and roughly 25% said they simply don’t trust COVID-19 vaccines. In addition, 1 in 10 said they did not view COVID-19 as a threat.