Republicans in at least 26 states have rolled back public health powers amid pandemic

Republican legislators in more than half of U.S. states, spurred on by voters angry about COVID-19 lockdowns and mask mandates, are taking away the powers state and local officials use to protect the public against infectious diseases.

A review by Kaiser Health News of hundreds of pieces of legislation found that, in all 50 states, legislators have proposed bills to curb public health powers since the pandemic began last year. While some governors vetoed bills that passed, at least 26 states pushed through laws that permanently weaken government authority to protect public health. More bills are pending in a handful of states whose legislatures are still in session.

In three additional states, an executive order, ballot initiative or state Supreme Court ruling limited long-held public health powers.

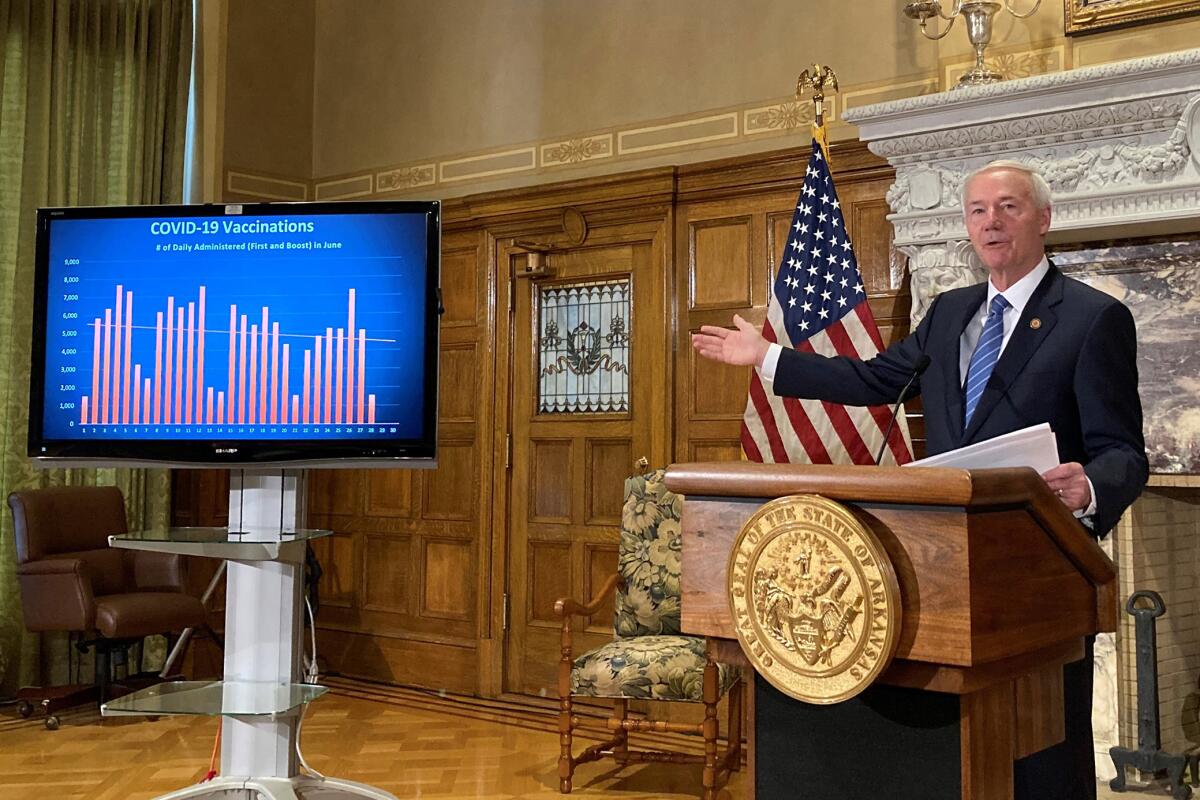

In Arkansas, legislators banned mask mandates except in private businesses or state-run healthcare settings, calling them “a burden on the public peace, health, and safety of the citizens of this state.” In Idaho, county commissioners, who typically have no public health expertise, can veto countywide public health orders. And in Kansas and Tennessee, school boards, rather than health officials, have the power to close schools.

President Biden on Thursday announced sweeping vaccination mandates and other COVID-19 measures, saying he was forced to act partly because of such legislation: “My plan also takes on elected officials in states that are undermining you and these lifesaving actions.”

All told:

- In at least 16 states, legislators have limited the power of public health officials to order mask mandates, or quarantines or isolation. In some cases, they gave themselves or local elected politicians the authority to prevent the spread of infectious disease.

- At least 17 states passed laws banning COVID-19 vaccine mandates or passports, or made it easier to get around vaccine requirements.

- At least nine states have new laws banning or limiting mask mandates. Executive orders or a court ruling limit mask requirements in five more.

Much of this legislation takes effect as COVID-19 hospitalizations in some areas are climbing to the highest numbers seen at any point in the pandemic.

“We really could see more people sick, hurt, hospitalized or even die, depending on the extremity of the legislation and curtailing of the authority,” said Lori Tremmel Freeman, head of the National Assn. of County and City Health Officials.

Public health officials are frustrated that they, not the coronavirus, have become the enemy. They say the rollbacks will have consequences that last long beyond this pandemic, diminishing their ability to fight COVID-19 surges today and to quarantine people during a measles outbreak in the future.

“It’s kind of like having your hands tied in the middle of a boxing match,” said Kelley Vollmar, executive director of the Jefferson County Health Department in Missouri.

The Delta variant of the coronavirus has taken on a decidedly American feel, mainly targeting those who just won’t get vaccinated.

But proponents of the new limits say they are a necessary check on executive powers and give lawmakers a voice in prolonged emergencies. Arkansas state Sen. Trent Garner, a Republican who co-sponsored his state’s successful bill to ban mask mandates, said he was trying to reflect the will of the people.

“What the people of Arkansas want is the decision to be left in their hands, to them and their family,” Garner said. “It’s time to take the power away from the so-called experts, whose ideas have been woefully inadequate.”

After initially signing the bill, Republican Gov. Asa Hutchinson expressed regret, calling a special legislative session in early August to ask lawmakers to carve out an exception for schools. They declined. The law is currently blocked by an Arkansas judge, who deemed it unconstitutional. Legal battles continue in other states as well.

A deluge of bills

In Ohio, legislators gave themselves the power to overturn health orders and weakened school vaccine mandates. In Utah and Iowa, schools cannot require masks. In Alabama, state and local governments cannot issue vaccine passports and schools cannot require COVID-19 vaccinations.

With a mandate for students to receive a COVID-19 vaccination, L.A. Unified puts itself out there for emulation, adulation, scorn and litigation.

Montana’s Legislature passed some of the most restrictive laws of all, severely curbing public health’s quarantine and isolation powers, increasing local elected officials’ power over local health boards, preventing limits on religious gatherings and banning employers — including in healthcare settings — from requiring vaccinations for COVID-19, the flu or anything else.

Legislators there also passed limits on local officials: If jurisdictions add public health rules stronger than state public health measures, they could lose 20% of some grants.

Losing the ability to order quarantines has left Karen Sullivan, health officer for Montana’s Butte-Silver Bow Public Health Department, terrified about what’s to come — not only during the pandemic but also for future measles and whooping cough outbreaks.

“In the midst of Delta and other variants that are out there, we’re quite frankly a nervous wreck about it,” Sullivan said. “Relying on morality and goodwill is not a good public health practice.”

Unleashing a fast-spreading coronavirus variant on a half-vaccinated population can lead to a vaccine-resistant strain.

While some public health officials tried to fight the national wave of legislation, the underfunded public health workforce was consumed by trying to implement the largest vaccination campaign in U.S. history and had little time for political action.

Freeman said her city and county health officials’ group had meager influence and resources, especially in comparison with the American Legislative Exchange Council, a corporate-backed conservative group that promoted a model bill to restrict the emergency powers of governors and other officials.

The draft legislation appears to have inspired dozens of state-level bills, according to the KHN review. At least 15 states passed laws limiting emergency powers. In some states, governors can no longer institute mask mandates or close businesses, and their executive orders can be overturned by legislators.

When North Dakota’s legislative session began in January, a long slate of bills sought to rein in public health powers, including one with language similar to ALEC’s. The state didn’t have a health director to argue against the new limits because three had resigned in 2020.

Fighting the bills not only took time but also seemed dangerous, said Renae Moch, public health director for Bismarck, who testified against a measure prohibiting mask mandates. She then received an onslaught of hate mail and demands for her to be fired.

In Santa Cruz County, two public servants became targets of an extremist network that threatened officials statewide over COVID-19 safeguards.

Lawmakers overrode the governor’s veto to pass the bill into law. The North Dakota Legislature also banned businesses from asking whether patrons were vaccinated against or infected with the coronavirus and curbed the governor’s emergency powers.

The new laws are meant to reduce the power of governors and restore the balance of power between states’ executive branches and legislatures, said Jonathon Hauenschild, director of the ALEC task force on communications and technology.

“Governors are elected, but they were delegating a lot of authority to the public health official, often that they had appointed,” Hauenschild said.

‘Like turning off a light switch’

When the Indiana Legislature overrode the governor’s veto to pass a bill that gave county commissioners the power to review public health orders, it was devastating for Dr. David Welsh, the public health officer in rural Ripley County.

People immediately stopped calling him to report COVID-19 violations, because they knew the county commissioners could overturn his authority. It was “like turning off a light switch,” Welsh said.

Another county in Indiana has already seen its health department’s mask mandate overridden by the local commissioners, Welsh said.

He’s considering stepping down after more than a quarter of a century in the role. If he does, he’ll join at least 303 public health leaders who have retired, resigned or been fired since the pandemic began, according to an ongoing KHN and AP analysis. That means 1 in 5 Americans have lost a local health leader during the pandemic.

“This is a deathblow,” said Brian Castrucci, CEO of the De Beaumont Foundation, which advocates for public health. He called the legislative assault the last straw for many seasoned public health officials who had battled the pandemic without sufficient resources while also being vilified.

Public health groups expect further combative legislation. ALEC’s Hauenschild said the group was looking into a Michigan law that allowed the Legislature to limit the governor’s emergency powers without Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s signature.

Curbing the authority of public health officials also has become campaign fodder, particularly among Republican candidates running further on the right.

While Republican Idaho Gov. Brad Little was traveling out of state, Lt. Gov. Janice McGeachin signed a surprise executive order banning mask mandates that she later promoted for her upcoming campaign against him. He later reversed the ban, tweeting, “I do not like petty politics. I do not like political stunts over the rule of law.”

At least one former lawmaker — former Oregon Democratic state Sen. Wayne Fawbush — said some of today’s politicians might come to regret these laws.

Fawbush was a sponsor of 1989 legislation during the AIDS crisis. It banned employers from requiring healthcare workers, as a condition of employment, to get an HIV vaccine, if one became available.

But 32 years later, that means Oregon cannot require healthcare workers to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Calling lawmaking a “messy business,” Fawbush said he certainly wouldn’t have pushed the bill through if he had known then what he does now.

“Legislators need to obviously deal with immediate situations,” Fawbush said. “But we have to look over the horizon. It’s part of the job responsibility to look at consequences.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. KHN is one of the three major operating programs at the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation.

KHN data reporter Hannah Recht, Montana correspondent Katheryn Houghton and Associated Press writer Michelle R. Smith contributed to this report.