Vaccinations lag for Medicaid patients as states struggle to reach poorest residents

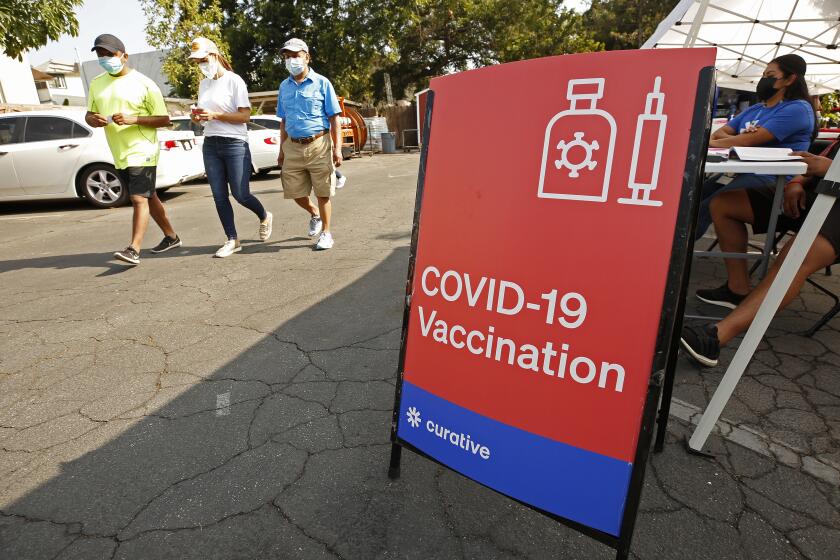

Medicaid enrollees are getting vaccinated against COVID-19 at far lower rates than other Americans as states struggle to improve access to the shots and change the minds of those who remain hesitant.

Efforts by state Medicaid agencies and the private health plans that cover low-income residents have been scattershot and hampered by a lack of access to state data about which members are immunized.

The problems reflect the decentralized nature of the health program, which is funded largely by the federal government but managed by the states. They also point to the difficulty in reaching Medicaid populations and driving home the importance of COVID-19 vaccines.

“These are some of the hardest-to-reach populations and those often last in line for medical care,” said Craig Kennedy, chief executive of Medicaid Health Plans of America, a trade group. Enrollees often face hurdles accessing the vaccines, including worries about taking time off work or finding transportation to a clinic, he said.

In California — which has nearly 14 million people in Medi-Cal, the largest Medicaid program in the country — 49% of enrollees age 12 and older are at least partly vaccinated. That compares with 74% for all Californians 12 and up.

Unlike Texas, Pennsylvania and some other large states, California provides its Medicaid plans with information from vaccine registries, which can help them target unvaccinated enrollees. They’re working with community groups to knock on doors in neighborhoods with low vaccination rates and providing shots on the spot.

This fall, the state will offer its Medi-Cal health plans $250 million in incentives to vaccinate their members, plus $100 million for gift cards worth up to $50 for enrollees.

Unleashing a fast-spreading coronavirus variant on a half-vaccinated population can lead to a vaccine-resistant strain.

In other states — such as Kentucky and Ohio — health plans are giving $100 gift cards to members when they get vaccinated.

While more than 202 million Americans are at least partly vaccinated against COVID-19, nearly 30% of people 12 and older remain unvaccinated.

Nationally, about 70% of Medicaid enrollees are at least 12 years old and eligible for the vaccines, according to a KFF analysis. But surveys show poor people are less likely to get a shot.

State Medicaid programs that can track their progress show modest results in vaccinating those who are old enough to be immunized:

- In Florida, 34% of Medicaid recipients are at least partially vaccinated, compared with 67% for all residents.

- In Utah, 43% of Medicaid recipients are vaccinated, compared with 68% statewide.

- In Louisiana, 26% of Medicaid enrollees are vaccinated, compared with 59% for the state as a whole.

- In Washington, D.C., 41% of Medicaid enrollees are vaccinated, compared with 76% of all residents.

“We know how we are doing, and it’s not great,” said Dr. Pamela Riley, medical director of the D.C. Department of Health Care Finance, which oversees Medicaid in the district.

Hemi Tewarson, executive director of the National Academy for State Health Policy, said she “had hoped there would not be this much of a disparity, but clearly there is.”

Medicaid agencies in several states — including Pennsylvania, Missouri, New Jersey and Texas — said they lack complete data on vaccination rates and don’t have access to state registries showing who has been immunized. Without those data, the vaccination campaigns are virtually flying blind, health experts say.

“Having data is Step One in knowing who to reach out to and who to call and who to have doctors and pediatricians help out with,” said Julia Raifman, assistant professor of health law, policy and management at Boston University.

Jana Eubank, executive director of the Texas Assn. of Community Health Centers, said her clinics would be grateful to know which Medicaid recipients are vaccinated to better target immunization campaigns.

“That would allow us to be more focused with our finite resources,” she said.

(The data would also help providers make sure people get their booster doses when they are eligible for them, she added.)

Guillermo Cozar waited months to get his vaccine because, he reasoned, he’d already had COVID last fall and didn’t think he would get sick again.

For years, Medicaid programs have worked with providers to improve vaccination rates. But now, Medicaid officials need more direction from the federal government to set up “a more clear and focused and effective approach” to get the pandemic under control, Raifman said.

Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, the administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, said the federal government is giving extra funding to state Medicaid programs to encourage COVID-19 vaccinations and urging states to remind enrollees that “vaccines are free, safe and effective.”

Kennedy, of Medicaid Health Plans of America, said getting shots to Medicaid enrollees is harder when states don’t share immunization data.

“We need access to the state immunization registries so we can make informed decisions to get those unvaccinated people vaccinated,” he said.

Plus, Medicaid agencies’ claims data don’t account for the many enrollees who get vaccinated at federal immunization sites and other places that don’t require insurance information.

California officials said they can track enrollee vaccination by linking to the state Department of Public Health’s immunization registry, which captures inoculations wherever they occur in the state.

As of Aug. 8, rural Lassen County had the lowest vaccination rate among Medi-Cal enrollees, with 21% having received at least one dose, according to data from the California Department of Health Care Services. San Francisco had the highest rate, 67%.

At 65%, San Francisco Health Plan had the highest vaccination rate of the two dozen Medicaid health plans in the state.

Dr. Fiona Donald, chief medical officer for the plan, said knowing which members are unvaccinated has helped its outreach effort, which includes regular calls offering help with transportation or connecting members with a doctor to answer concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness. The city’s high overall vaccination rate, topping 84% of eligible people, has given the plan a boost, she noted.

Kern Health Plan in Bakersfield had the lowest vaccination rate of any California Medicaid plan, at 33%. In the last month, Kern has supported a community effort to knock on doors to educate people about the vaccines and offer a $25 Walmart gift card as an incentive. The work has been supported by state data showing where vaccination rates lag.

There’s a white privilege to denouncing everyone who refuses to get a COVID-19 vaccine. For those who are Black, there’s systemic racism to consider.

John Baackes, CEO of L.A. Care Health Plan, said he remains skeptical about paying people to get their shots and said it could upset enrollees who already have been vaccinated and won’t qualify for cash or a gift card.

“We don’t think gift cards are going to move the needle very much,” he said.

As part of its strategy to increase vaccinations, the health plan called members at high risk for COVID-19 complications to get them into walk-up or drive-through immunization sites, and it helped homebound members get shots where they live. About half the plan’s eligible enrollees have received at least one dose.

Richard Sanchez, CEO of CalOptima, the Medicaid health plan in Orange County, said offering $25 Subway gift cards helped increase vaccinations among members living at homeless shelters. As of mid-August, about 56% of its eligible enrollees were at least partly vaccinated.

“We are not where we should be, and the nation is not where it should be,” Sanchez said.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. KHN is one of the three major operating programs at the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation.