How COVID pandemic changed methadone treatment for addiction

Here’s one more lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic: It appears safe to relax restrictions on methadone, the oldest and most stigmatized treatment drug for opioid addiction.

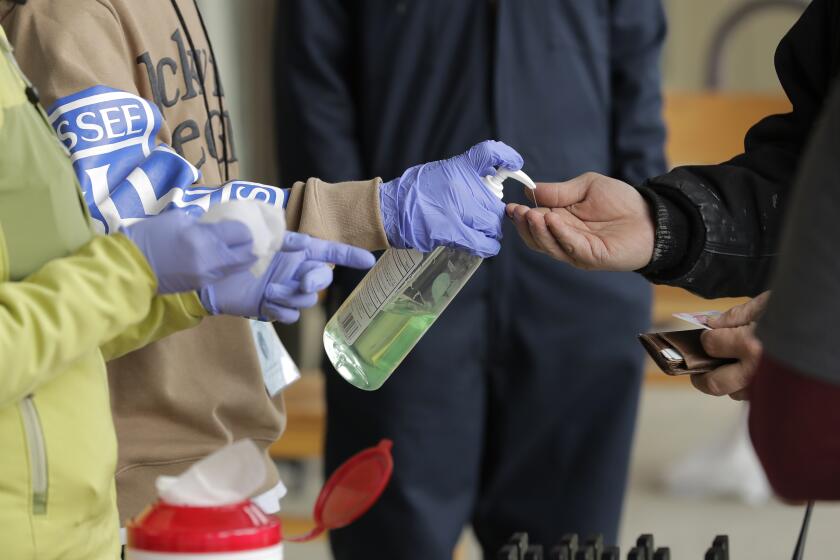

Last spring, with the coronavirus shutting down the nation, the government told methadone clinics they could allow stable patients to take their medicine at home without supervision.

Early research shows it didn’t lead to surges of methadone overdoses or illegal sales. And the phone counseling that went along with take-home doses worked better for some people, helping them stay in recovery and get on with their lives.

U.S. health officials are studying the changes, their impact and how they might be continued.

Since the 1970s, rigid rules have guided methadone treatment, requiring most people to line up and sip the liquid medicine from small cups while being watched by employees at clinics. Only long-term patients were allowed to take home more than a day’s dose.

Now, scientists are gathering information to put those rules — never rigorously tested — under scrutiny.

“It took a pandemic to change the climate to allow us to actually study it,” said Dr. Ayana Jordan of Yale University School of Medicine, who is among researchers studying the methadone rule changes. “If we roll these policies back post-COVID, it’s going to be devastating.”

More than 400,000 people in the United States receive methadone as part of their treatment for addiction to opioids such as heroin, fentanyl and painkillers. Methadone, an opioid itself, can be dangerous in large amounts, but when taken correctly, it can stop drug cravings without causing a high. People can hold jobs and work on rebuilding their lives.

Drug rehabs across the U.S. have experienced coronavirus flare-ups or COVID-19-related financial problems, forcing them to close or limit operations.

Scott Mancini, 58, a retired truck driver in Providence, R.I., has been taking methadone for a heroin addiction since 1989. Before the pandemic change, Mancini could take home a six-day supply, requiring a weekly stop at the clinic.

“You’re tied down,” Mancini said of the old system. Now, with a 28-day supply, he can enjoy a long camping trip or family visit.

“It’s worked very well for me and lot of other people,” Mancini said. “I think it’s time we rewrite the rules of the programs throughout the country because the rules haven’t changed in years.”

Not all methadone clinics loosened the rules, but Rhode Island’s oldest methadone program, CODAC, where Mancini is a patient, jumped at the chance to use phone counseling and give more take-home doses. In a patient survey conducted by Brown University, most people said phone counseling was useful.

“There are two things we learned from COVID,” said CEO Linda Hurley. “Take-homes do not need to be severely restricted and telehealth works.”

Because of how opioids act on the brain, people dependent on them get sick if they stop using. Withdrawal can feel like a bad flu with cramping, sweating, anxiety and sleeplessness. Cravings can be so intense that relapse is common.

Methadone eases those symptoms.

A rise in deaths of homeless people is being driven by drug overdoses involving fentanyl, a report by L.A. County public health officials concludes.

The idea behind the Nixon-era rules was to prevent illegal street sales and overdoses.

“I understand the concern, but there are ways to address those issues,” such as urine screening to make sure patients are taking their methadone, said 37-year-old Lyna Chaves of Pleasantville, N.J.

She now gets five days of take-home methadone from John Brooks Recovery Center under the pandemic rules. Working to become a peer support specialist, she also distributes donated food, toothpaste and other items to people who are homeless.

Rutgers University plans to analyze New Jersey health data for any bump in methadone overdoses. In interviews with researchers, New Jersey methadone providers support the relaxed take-home rules, said Rutgers researcher Stephen Crystal.

People who live far from clinics or hold steady jobs are particularly burdened by daily trips to be watched getting a dose, Crystal said.

When the government eased restrictions, it said stable patients could receive 28 days of take-home methadone and less-stable patients could get 14 days. Clinics were allowed to figure out which patients were eligible; many relied on their experience and previous government criteria, such as time in treatment and absence of criminal activity.

Two decades of progress in closing a yawning gap between the life expectancy of Black and white Americans has been erased by COVID-19.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is studying the changes and how they might be continued, said Miriam Delphin-Rittmon, assistant secretary for mental health and substance use.

In the meantime, a new federal rule that just took effect will allow the expansion of mobile vans to bring methadone treatment to rural and hard-to-reach areas. There are a dozen or so operating now.

Methadone vans would be a good way for states to spend their money from opioid lawsuit settlements, said Beth Connolly, who directs the Pew Charitable Trusts’ substance use prevention and treatment project. As soon as next year, states could begin to see money from settlements with prescription drugmakers and distributors.

Overdose deaths soared to a record 93,000 last year, the U.S. government reported last month, with more than 60% involving fentanyl.

The pandemic provided the opportunity to give more take-home doses, said Allegra Schorr, who leads a coalition of addiction treatment providers in New York. “This worked. Why would you just return to the way things were?”