Coronavirus confusion: What’s the difference between a variant and a strain?

As if one coronavirus wasn’t enough to worry about, it now seems there are versions of it popping up all over the world.

There’s one from the United Kingdom, which looks to be about 56% more transmissible than its predecessors and is taking the U.S. by storm.

There’s one from South Africa, which is proving to be adept at evading our brand-new COVID-19 vaccines.

Yet another from Brazil may have an uncanny ability to reinfect people who have already survived a bout of COVID-19.

And then there’s the homegrown coronavirus that appears to be spreading faster in California than any of its competitors and may have played a key role in the state’s deadly holiday surge.

Researchers are racing to learn more about these and other incarnations of SARS-CoV-2: Are they more contagious? More deadly? More impervious to treatment?

Meanwhile, the rest of us are trying to get our heads around a more fundamental question: Are they variants or strains?

It seems like there ought to be an easy answer. Yet like with so many aspects of the pandemic, there isn’t.

COVID-19 patients who take months to overcome their coronavirus infections despite treatment can become incubators of dangerous new strains.

Before we proceed, let’s pause for a brief review of basic genetics:

Humans share a common genome that varies from person to person. These differences account for our variation in height, hair color and other traits — what scientists call a phenotype.

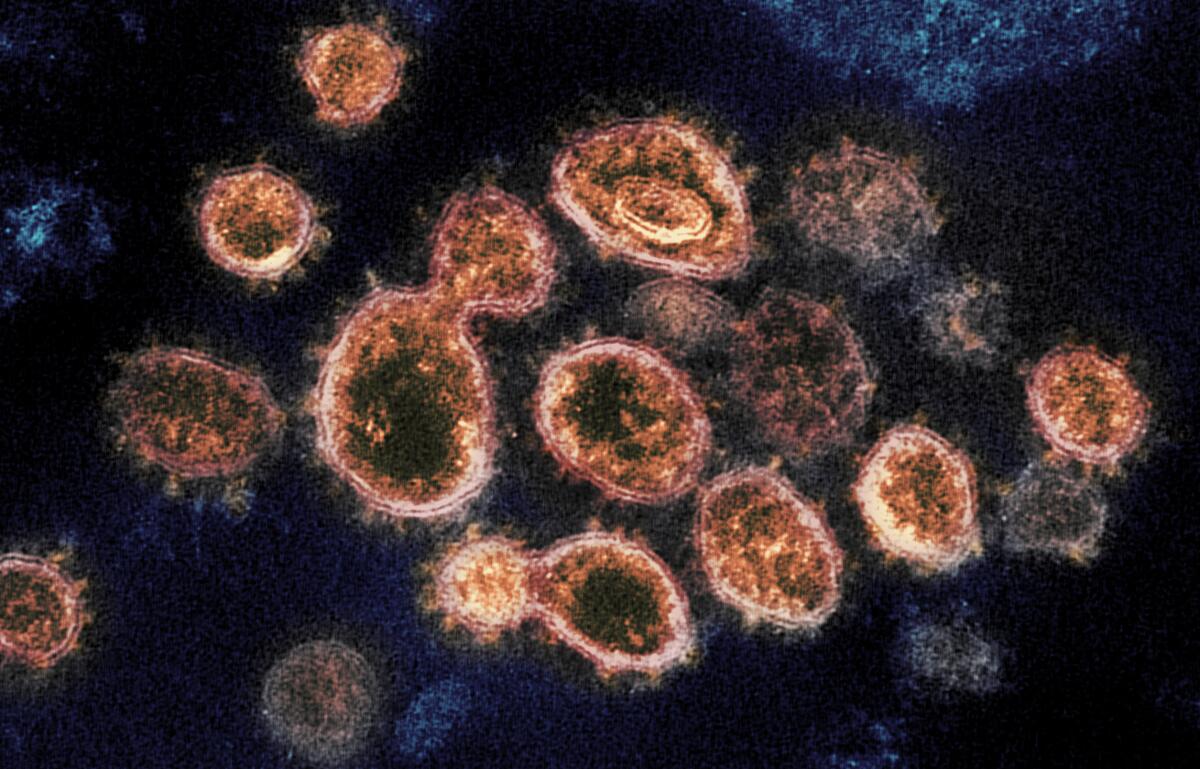

Similarly, SARS-CoV-2 coronaviruses share a genome that looks a little different from specimen to specimen.

Each time a virus makes copies of itself, one or more of the letters in the genome can be written incorrectly. Coronaviruses are pretty good at proofreading, but mistakes still get through. This is how genetic mutations arise, and it’s all perfectly normal.

If a mutation makes it more difficult for the virus to replicate — for instance, if it results in a physical change that hampers its ability to get inside a host cell — that virus will die out and take the mutation along with it. On the other hand, if a mutation gives the virus a competitive advantage, it will spread more quickly than its rivals.

There are also cases where a virus with a particular mutation just happens to take off because it’s in the right place at the right time to get in on the ground floor of an outbreak. Geneticists call this a “founder effect.”

When a mutation changes a virus’ genome, it becomes a new variant. Beyond that, things get tricky.

California scientists have discovered a new coronavirus strain that appears to be propagating faster than any other variant in the Golden State.

Confusion over the terms “variant” and “strain” predate this coronavirus. It seems virologists never got around to defining their terms.

Here’s how a group of scientists explained the predicament in a 2013 article in the journal Archives of Virology, in which they spelled out what to call members of the Filoviridae family, which includes the Ebola and Marburg viruses:

“It is unclear how to distinguish their individual subclasses (strains, genetic variants, genotypes, mutants, etc.), mainly because of a lack of definitions for these terms and the absence of generally applicable guidelines for assigning viruses to them.”

A pair of scientists stepped into the breach last month with a workable definition for the COVID-19 era.

The distinction between a variant and a strain hinges on whether the virus in question behaves in a distinct way, according to Dr. Adam Lauring, who studies the evolution of RNA viruses at the University of Michigan, and Emma Hodcroft, an expert on viral phylogenetics at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

“Genomes that differ in sequence are often called variants,” Lauring and Hodcroft explained in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. “Strictly speaking, a variant is a strain when it has a demonstrably different phenotype.”

In other words, a particular coronavirus specimen may contain one or more mutations that another specimen lacks. If there is no detectable functional difference, it is merely a variant.

However, if those mutations make the specimen more transmissible than its predecessors, or endow it with an added ability to evade a drug or vaccine, or alters it in another meaningful way, then it qualifies as a distinct strain.

Health officials set aside carefully considered plans for rolling out COVID-19 vaccines and made the shots widely available. That may hasten the pandemic’s end.

The two terms have been thrown around interchangeably, especially by those who have become armchair virologists over the course of the pandemic. But they are not synonymous.

“The distinctions are important,” Lauring and Hodcroft wrote.

Another definition for strain comes from Nancy R. Gough, a scientist and editor who explains the biological world on her website, Bioserendipity. In her telling, a viral variant that becomes dominant in its population earns the right to be called a strain.

It doesn’t matter whether that dominance was achieved through superior genetics or by happenstance, she adds.

By these measures, the virus from South Africa qualifies as a strain because its response — or lack thereof — to COVID-19 vaccines sets it apart from other versions of SARS-CoV-2. Its behavior is so singular that vaccine researchers are designing booster shots to target it.

The coronavirus from the U.K. counts as a strain as well because it spreads more readily than other variants. Indeed, researchers at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have forecast that the U.K. virus is spreading so fast that it’s on track to become America’s “predominant variant in March.”

If that happens, it will be a strain twice over.