They’re not really called ‘murder hornets.’ And they’re probably not as bad as you think

When news of the Asian giant hornet’s arrival in the United States first broke, the public was understandably worried: First the coronavirus, now “murder hornets”? What’s next, three days of darkness?

But bug experts from Washington, where the hornet was discovered in the U.S., to California agree that the 2-inch hornet is probably not worth all the buzz it has generated — at least not yet.

“It’s not an existential threat; it’s something that can be managed. You just have to know that they’re there and take the necessary steps,” said Doug Yanega, senior museum scientist at UC Riverside’s Entomology Research Museum. He helped Washington scientists identify the hornets when they were first found.

“It’s like letting a virus spread — you don’t want to let your guard down.”

The Washington State Department of Agriculture has confirmed only two Asian giant hornets, both spotted late last year in Blaine, in the crook of the northwest corner of the U.S. There are also two unconfirmed reports of hornet sightings about eight miles down the road in Custer, according to Washington State University. And just across the border — and the skinny Strait of Georgia — in British Columbia, Canada, a colony of the Asian giant hornets was found and eradicated in September.

But so far that’s it, and scientists hope it stays that way.

“We’re still trying to determine the extent of the infestation,” said Tim Lawrence, associate professor and Island County extension director at Washington State University. “We don’t want it here.”

The main concern about the Asian giant hornet is its potential to harm honeybee populations. The queen hornet usually emerges in April to begin feeding and building up her nest of worker hornets. By late summer or early fall, her worker hornets begin foraging for food, swarming beehives, cutting off bees’ heads and sucking out the hive’s larvae and pupae to bring back to their burgeoning nest.

“What the hornet does is it feeds on — it preys on — honeybees,” said Dessie Underwood, an entomologist and the chair of Cal State Long Beach’s Department of Biological Sciences. “Just like a lion feeds on a gazelle — you don’t call it a murderous lion. Everyone has to eat something.”

The hornets are unlikely to attack humans — though if they do, they pack a painful punch.

But an Asian giant hornet’s sting isn’t likely to kill humans. In Japan, said Susan Cobey, a bee breeder at the Washington State University, about 50 people die every year from hornet stings, and that number is probably attributable to allergies. In the United States, an average of 62 people die each year from hornet, wasp or bee stings, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Early genetic testing shows that the Canadian colony originated in Japan, and at least one of the Washington hornets came from South Korea, said Karla Salp, public engagement specialist with Washington’s agriculture department. Several scientists said they believed the hornets likely hitched a ride on cargo brought to an American port from Asia.

European honeybees, which have long lived in North America, are not equipped to defend themselves against the Asian giant hornet. In Japan, where the hornet typically lives, Asian honeybees have evolved a defense mechanism, Cobey said. The bees make a massive ball around the hornet scouts and smother them to death with the heat of their beating wings.

Honeybees in the United States already face existential threats of increased pesticides, loss of habitat and a changing environment, she added.

A newly introduced hornet could endanger the bee population and have a domino effect on the American food supply. Fruits, vegetables and even plant-grown animal feed could suffer without enough pollinating bees.

“The crunch is kind of now,” Cobey said. “If we can catch these queens before they establish big nests, that’s the goal.”

Anyone who thinks they may have spotted an Asian giant hornet can report it to their state’s agriculture department. People can also help by not killing innocent bumblebees, Lawrence said.

“If we get through May and June and July and nobody has spotted any of these wasps, then we’re probably free and clear. The jury is still out,” said Yanega, the UC Riverside entomologist. “There is a reason for concern, but it’s not the level of threat that people think there is.”

As for whether Californians could expect to see them, this particular hornet comes from a region in Japan with warm, wet summers and cold dry winters, Long Beach State’s Underwood said. Not exactly a California climate.

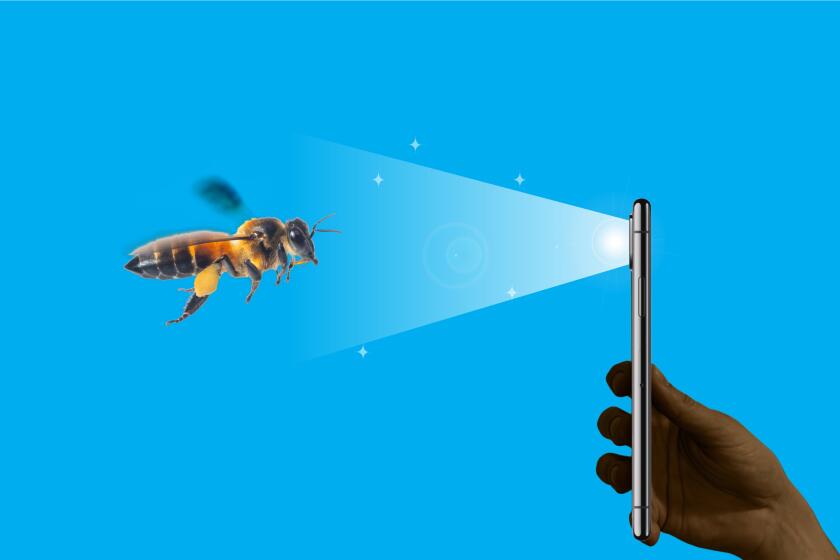

Celebrate World Bee Day by participating in a global count of pollinators, including honeybees, with a free app available May 1.