Feeling drained by coronavirus quarantine? Science can explain why

When 13 passengers from the Diamond Princess cruise ship arrived in Nebraska in mid-February, David Cates was determined to make their mandatory stay as pleasant as possible.

The passengers were among the first Americans known to be exposed to the coronavirus and had been ordered to remain isolated at a national quarantine center at the University of Nebraska Medical Center for at least two weeks, or until they no longer tested positive for the disease. Some would spend more than a month at the center before returning home.

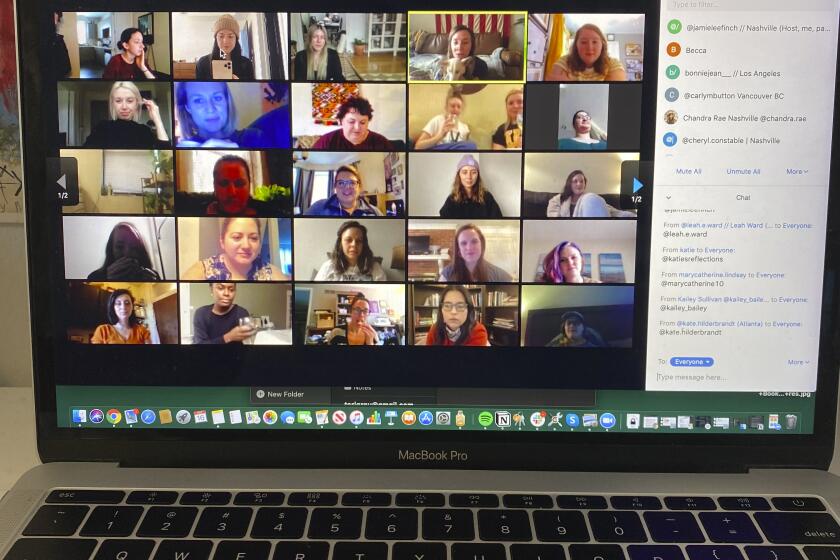

As a psychologist and behavioral health consultant for the quarantine center, it was Cates’ job to tend to their emotional well-being while they remained isolated from friends and family in the outside world. He convened a daily “town hall” meeting via teleconference so those in isolation could ask doctors questions about the virus, give nurses feedback on the food they were served, and talk to case workers about tracking down their luggage and booking flights home.

He also taught them coping techniques such as meditation, deep breathing and cultivating gratitude to help them build resilience.

Months later, he is still receiving thank-you notes.

“What we were doing was giving them as much control over their lives and environment as possible,” Cates said. “If the story had ended there, it would have been great. Instead, we are in a global pandemic, and now we have to take care of everybody.”

As millions of Americans face their second month of stay-at-home orders, scientists and health officials increasingly fear that physical distancing could take a grave toll on our collective mental health.

Research suggests that people forced to live in quarantine conditions face a greater risk of anxiety, depression, anger, irritability, insomnia and post-traumatic stress symptoms. The longer a quarantine lasts, the worse its impact on psychological well-being.

“There is no doubt that restrictive stay-at-home measures have been quite isolating for people, and all the more for people who are already isolated and vulnerable,” said Dr. Michael J. Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization’s Health Emergencies Program.

But stopping the virus must come first, he said.

“It is not easy, but it is something we must endure until we have in place other measures to suppress this disease,” he said.

The coronavirus changed our lives. Health experts discuss how we might get back to normal.

To help officials manage the mental health repercussions of long-term physical distancing, researchers at King’s College London published a review of scientific studies on the psychological impacts of quarantine, including ones implemented to counter the spread of Ebola, SARS, MERS and H1N1 influenza.

The authors found that the key stressors that lead to psychological distress include boredom, frustration, inadequate supplies, limited information and financial loss, and that these effects can linger long after life returns to normal. For instance, one of the studies found that among hospital workers, being quarantined was a predictor of post-traumatic stress symptoms even three years after the isolation ended.

The findings suggest a few ways officials can mitigate the psychological impact of quarantine: Keep the isolation as short as possible, ensure those in quarantine know why they must stay isolated, thank them for their sacrifice, and make sure everyone has access to the supplies they need.

It is also essential that people can stay in touch with others. “An inability to do so is associated not just with immediate anxiety, but longer-term distress,” they wrote.

Steve Cole, a UCLA researcher who studies the physiological effects of loneliness, said actively seeking social connection is essential to staying not only emotionally healthy but physically healthy as people isolate from each other.

In his own work, he’s found that feelings of loneliness trigger the body’s immune system to increase its inflammatory response. That response is useful for fighting off bacterial infections, but it also creates what he calls a “fertilizer” for other diseases like cancer, Alzheimer’s, and cardiovascular disease. (As it happens, some patients with severe cases of COVID-19 suffer not just from the virus’ attack on the lungs but from an overactive inflammatory response.)

This may explain why previous studies have found that people with strong social relationships are 50% more likely to be alive at the end of a study period compared to those with poor or insufficient social relationships. In fact, this research suggests that loneliness is as dangerous to your health as smoking, and even worse than obesity.

Cole said the connection between loneliness and inflammation may have developed thousands of years ago when being alone would have made our ancestors more vulnerable to an attack by a saber-toothed tiger or made it more difficult to recover from an accident, like being injured by a falling branch.

“This program in our body was set up for a world we no longer inhabit,” he said.

The good news is that our current state of physical isolation does not have to lead to loneliness, he said.

“With social support, you can interrupt a lot of that threat-related physiology,” he said. “Staying connected to purpose and meaning in your life is the single most powerful resilience against that impact.”

Is the phrase “social distancing” sending the wrong message to millions of Americans struggling to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic? Some experts think so.

Dr. Jay Buckey, a former NASA astronaut who now works at the Dartmouth Geisel College of Medicine, has spent the past decade developing an online tool to help people manage the psychological fallout from a different type of isolation: the stress, depression and interpersonal conflict that can occur on a long-term spaceflight.

“Living in isolation and confinement with a small number of people for a long time is a psychological challenge,” he said.

That’s something billions of people have been learning first-hand on Earth.

Buckey’s experience with astronauts suggests that many of the issues that emerge in isolation are sharper versions of the problems we experience in daily life.

“Maybe you were already stressed about something, but you had outlets that were working for you, and now you are cut off from them,” he said.

The tool he created, called PATH, is designed to help users manage difficult emotions. Based on behavioral therapy, it helps people look clearly at how they are thinking about a situation and understand how that thinking influences the actions they take. (Though designed for astronauts, PATH is available for free to the Earth-bound public as well.)

Another analog for our current state can be found in the experience of those who spent time in the Antarctic with a small group of people for a long period, said Larry Palinkas, a professor at the School of Social Work at the University of Southern California.

Palinkas’ work on the mental health of polar trekkers and those who live in research stations has revealed that one of the hallmarks of adapting to isolation and confinement is a willingness to let go of control.

“You have to be flexible,” he said. “If you are highly demanding of yourself and others, you are going to have a harder time.”

He also found that people tend to be able to manage the first half of their isolation — whether it lasts for two weeks or two years — but when they reach the halfway point, their resolve dips.

“In the first half you conserve your emotional resources, engage in active forms of coping and you do well,” he said. “In the second half, people often experience a letdown.”

One of the profound challenges of our current situation is that no one knows when it will end. “The fear is that our emotional resources will become depleted and we will become physically and mentally exhausted,” he said.

However, living through isolation can have a positive outcome as well, Palinkas said. It’s known as salutogenesis, and it’s the reward that comes from coping with stress and being more self-sufficient.

In one of his early studies, he found that Navy personnel assigned to the Arctic in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s had fewer hospital admissions and mental health problems when they returned home.

“The idea is if you can survive an experience like this,” he said, “it results in a sense of accomplishment and a feeling like, ‘I can handle anything.’”