How UV light may protect us from the coronavirus

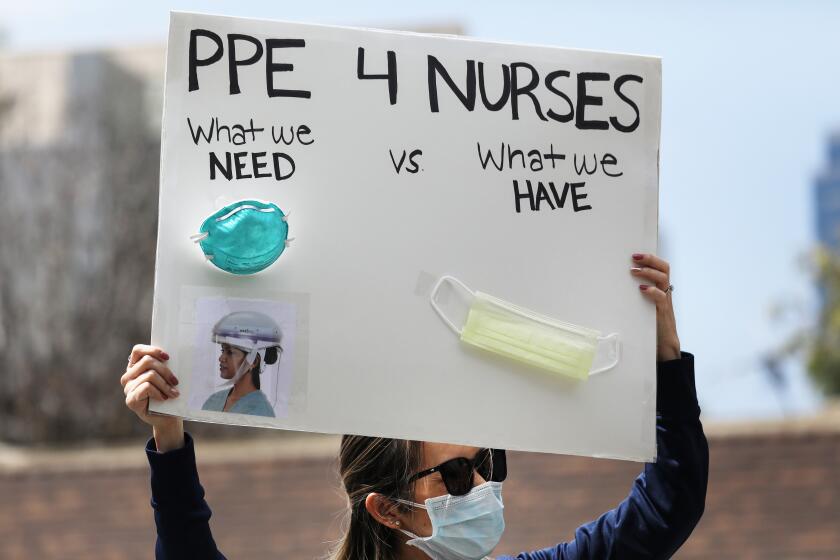

The stealthy new coronavirus has turned face masks into ubiquitous accessories, and that means millions of Americans are looking for ways to keep them clean.

Can ultraviolet light do the job?

Ideally, single-use face masks should be worn once and then thrown away, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s certainly true of the top-of-the-line N95 masks used by healthcare workers that are designed to filter out 95% of tiny particles when properly fitted to a wearer’s face.

But last week, the CDC released new guidance on decontamination methods for emergency situations, such as the one healthcare workers are facing with the COVID-19 pandemic. Any disinfection process would need to kill the coronavirus without harming an N95 mask’s ability to filter particles or fit snugly to the skin.

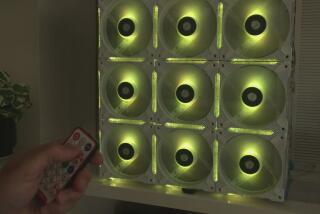

Ultraviolet germicidal radiation is one of the methods presented by the CDC, and UV light has generated great interest from the public. It’s already used in hospitals to disinfect contaminated surfaces. And there’s a fairly robust market of devices aimed at consumers, such as disinfectants for sleep apnea machines (although no such devices have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration so far). Other products purport to clean cellphones and disinfect water bottles.

Here’s a closer look at what ultraviolet light is and why it could be a useful tool in combating the coronavirus in certain situations.

What is UV light?

Ultraviolet light, also known as UV light, is invisible to humans. Though it’s adjacent to visible light on the electromagnetic spectrum, its wavelengths are just too short for our eyes to register and see.

UV rays are also high-energy, so while we can’t see them, we certainly feel their effects. For instance, ultraviolet light generated by the sun is what gives you a tan — or a sunburn. It can also lead to skin cancer.

The FBI thwarted a fraudulent deal for 39 million masks needed by healthcare workers fighting coronavirus.

Ultraviolet light falls into three categories, according to the World Health Organization:

• UVA: This is the lowest-energy form of UV, and it accounts for about 95% of the ultraviolet light that reaches the Earth from the sun. It can penetrate deep into the skin’s layers, which makes it responsible for the early tanning effect. It also contributes to skin aging, wrinkling and possibly skin cancer.

• UVB: This higher-energy type of ultraviolet light can permeate the skin’s superficial layers. It’s responsible for delayed tanning (and burning), and is a big contributor to skin cancer and aging. Most of the UVB that comes our way is absorbed by the Earth’s ozone layer, so it only makes up about 5% of the solar UV that reaches Earth.

• UVC: The highest-energy category of ultraviolet light — any higher and you’d be in X-ray territory — is also the most damaging. Luckily, the ozone layer and atmosphere completely absorb it.

The UV light used in medical disinfection devices is a particular wavelength of UVC.

How does UV disinfect stuff?

Ultraviolet light can penetrate the cells of pathogens and damage the DNA or RNA that contain their genetic code, said Jim Malley, an environmental engineer at the University of New Hampshire.

There’s also some evidence that UV can damage the amino acids and proteins that either protect the virus or allow it to attach to and infect a host cell.

So it’s already in use?

Yes. People have been disinfecting things with UV for more than a century, according to Ron Hofmann, an environmental engineer at the University of Toronto.

Many experts say the first full-scale UV disinfection system for water treatment was used in Marseilles, France, in 1910, Malley said.

Modern UV devices come in a range of shapes and sizes. Some are not much bigger than cellphones. Others can be as large as a Cadillac Escalade — or multiple Escalades parked nose to bumper, in the case of the systems used to disinfect drinking water in Los Angeles and New York, Malley said.

Many midsize UV machines — about the size of a large garbage bin — are used in hospitals to disinfect patients’ rooms after they’ve left.

Can I disinfect myself with UV light?

No way. UV will damage your skin and eyes, and you won’t even know it’s happening until it’s too late. And UVC, which is typically used in commercial devices, is the most damaging of the bunch. So, no, you absolutely should not try to use UV on your body. (The World Health Organization agrees.)

That’s particularly important because humans can’t rely on their intuition to tell whether they’re near a source of UV that they should be avoiding, Malley said.

“You don’t really get a second chance,” he said. With a high enough dose from a powerful decontamination system, “that kind of UV damage would be so intense that you would lose your sight.”

If UV is already used in hospitals, what’s the big deal?

The problem is that there hasn’t been a lot of research to determine whether UV is effective at sanitizing masks and other personal protective equipment. Nor has there been much research into making a device that would actively do so. (After all, these masks are only supposed to be used once before they’re thrown away — reuse was not in the original plan.)

Using UV sanitizers on masks is not as straightforward as it might seem. It’s much easier to sanitize smooth, flat hospital surfaces with ultraviolet light, such as floors and medical equipment. Since UV can only disinfect what it shines on, any shadows cast by a mask’s tiny folds might prevent those spots from being decontaminated, Hofmann said.

Can I disinfect my own mask with UV?

First off, you shouldn’t be worrying about disinfecting an N95 mask if you aren’t a health worker on the front lines of patient care. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says these top-of-the-line masks should be reserved for those who need them most.

For the rest of us who are simply trying not to become infected — or infect others — when we visit the grocery store, the CDC recommends wearing a cloth facial covering that can be laundered clean.

‘We may be moving gently at this point toward the Asian culture,’ one health expert says of everyday mask-wearing.

That said, there aren’t any clear independent standards in place to determine whether consumer-oriented UV disinfection devices are truly effective.

Keep in mind, UVC devices need to operate in a specific wavelength band, which historically has been in the range of 254 nanometers, to be effective. Researchers are working on developing other specific wavelengths for certain applications, but the point is that any old UVC wavelength won’t work.

“You’d want to be very careful about doing your homework and make sure that the device you have has actually been proven to do the job,” Hofmann said.

Device makers have been caught making false claims about what their UV disinfectors can do.

Plus, improper handling of a powerful UV device comes with risk of serious skin and eye damage, scientists said.

Can I disinfect my stuff with UV from sunlight?

“If we have time on our hands, sunlight is wonderful,” Malley said. But “it takes a long time.”

Like, a really long time. For the amount of time it would take, you’re probably better off putting a mask in a brown paper bag and hanging it off a well-aerated porch for seven days or so, Malley said. By then, the pathogen ought to be dead anyway.