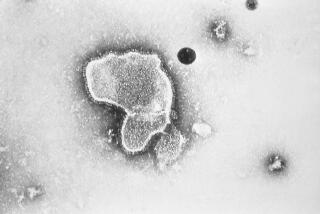

Old vaccines being tested against the new coronavirus

Scientists are dusting off some decades-old vaccines that were developed long before the emergence of the new coronavirus from China to see whether they can provide a little stopgap protection against COVID-19 until a more precise shot arrives.

It may sound like an odd idea, since vaccines are designed to target a specific disease. But shots made using live strains of bacteria or viruses seem to boost the immune system’s first line of defense, offering a more general way to guard against pathogens. Sometimes, that translates into at least some cross-protection against other, completely different bugs.

There’s no evidence yet that the approach would rev up the immune system enough to make a difference against the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. But given that a brand-new vaccine is expected to take 12 to 18 months, some researchers say it’s time to give this approach a try, starting with a tuberculosis vaccine.

More than 130 labs around the world are working to develop a COVID-19 vaccine. But what would it take to vaccinate everyone by early next year?

“This is still a hypothesis,” said Dr. Mihai Netea of Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands. But if it works, “it could be a very important tool to bridge this dangerous period until we have on the market a proper, specific vaccine.”

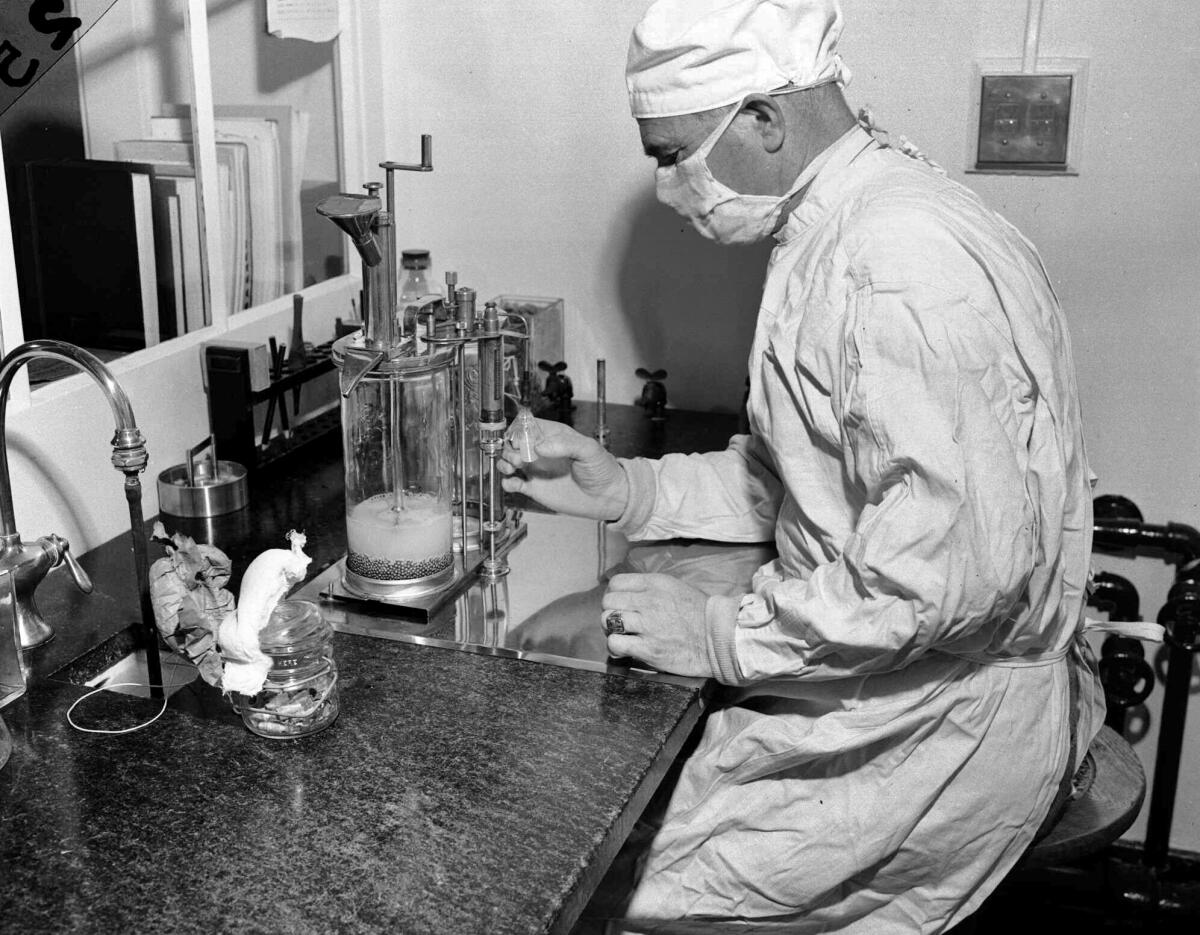

Already nearly 1,500 Dutch healthcare workers have rolled up their sleeves for one study that Netea’s team is leading. It uses a TB vaccine named BCG, which is made of a live but weakened bacterial cousin of the TB germ.

In Australia, researchers hope to enroll 4,000 hospital workers to test BCG too, and 700 already have received either the TB vaccine or a dummy shot. Similar research is being planned in other countries, including the U.S.

It’s way too soon for anyone to get their hopes up. On Monday, the World Health Organization issued a stern warning not to use the TB vaccine against the coronavirus unless and until studies prove it works.

Other vaccines may be tested as well. Possibly next in line: An oral polio vaccine made of live but weakened polio viruses. The Baltimore-based Global Virus Network hopes to begin similar studies with that vaccine and is in talks with health authorities, according to network co-founder Dr. Robert Gallo.

Rapid studies are needed to determine whether there could be “long-ranging effects for any second wave of this,” said Gallo, who directs the Institute of Human Virology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

At the U.S. National Institutes of Health, researchers are in early discussions about proposals to study the TB and polio vaccines as a possible COVID-19 defense, said agency spokeswoman Jennifer Routh.

Live vaccines are risky for people with weakened immune systems, and shouldn’t be tried against COVID-19 outside of a research trial, said Dr. Denise Faustman, immunobiology chief at Massachusetts General Hospital, who is planning a TB vaccine study.

“You can’t just roll it out,” she stressed. But “it’s kind of an amazing opportunity to prove or disprove this off-target effect.”

Creating a vaccine capable of preventing the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 will take many months — if not a year or more. These are the steps involved.

Years ago, scientists began noticing with several live vaccines what Dr. Victor Nizet, an immune expert at the UC San Diego School of Medicine, calls “an important curiosity that people have been interested in trying to harness.”

BCG is given mostly to newborns in developing countries, and it offers only partial protection against TB, a bacterial infection. But during childhood, the vaccinated tots had better overall survival, including from respiratory viruses, observational studies showed.

In 2018, Netea’s team showed that BCG stimulates initial immune defenses enough that it at least partly blocked another virus given experimentally a month later.

Clues about the oral polio vaccine first emerged from the former Soviet Union, said Konstantin Chumakov, a vaccine specialist at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, who stressed that he was not speaking on behalf of the FDA. His mother was a Soviet scientist who in the 1970s published research showing flu cases dropped markedly after oral polio vaccination.

In 2015, Danish researchers also found some hints of cross-protection after oral polio vaccinations. The oral drops still are used in developing countries, while the U.S. and other areas that have eliminated polio use the inactivated shot for routine childhood vaccines.

There are overlapping types of immune defenses. The usual goal of a vaccine is to prime the body to recognize a specific health threat and make antibodies capable of fighting back when that particular bug comes along.

But that takes time. So at the first sign of infection, white blood cells spring into action to fend off the invader in other ways — what’s called innate immunity. If they fail, then the body creates its more targeted special forces to join the fight.

BCG appears to be reprogramming innate immune cells so they can more readily eliminate the germ up front, Netea said.

Scientists who aren’t involved in the effort to try these vaccines against the new coronavirus say the test is worthwhile.

“The scientific rationale I think is quite logical,” Nizet said. “The unknown is whether coronaviruses are in the spectrum of things that are efficiently protected” by that first-line innate immunity.

Some scientists have theorized that countries with large BCG-vaccinated populations might fare better in the pandemic. But given problems with accurately counting the toll, it’s far too early to draw any conclusions, a caution the WHO reiterated Monday.