Why we should learn to accept the coronavirus craziness

Thanks to the new coronavirus, our plans for the future, once so clear and reasonable, now seem hazy and improbable.

Who knows when our kids will go back to school, or when we will return to the office? Nobody can say how long dine-in restaurants will remain closed, or when we can finally meet friends for a much-needed drink.

When can we pray with our congregations again? Throw a birthday party? Go to the movies?

And how long can we live with all this uncertainty and not lose our collective minds?

“It is very disorienting,” said Alison Holman, a health psychologist at UC Irvine. “It’s like reality isn’t reality right now.”

Life will return to normal, someday. But the end of this liminal time feels a long way off.

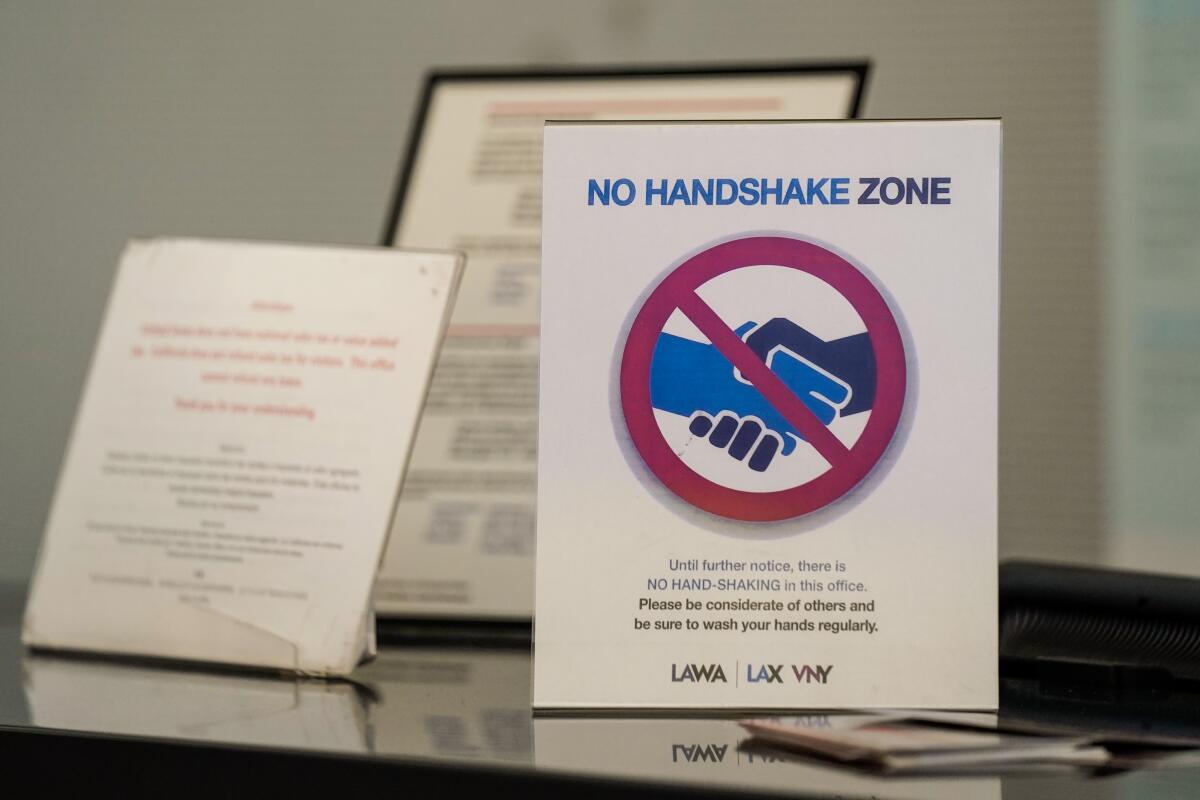

The social distancing measures we are all taking — avoiding crowds, staying at least 6 feet away from anyone we don’t live with — are not expected to end any time soon.

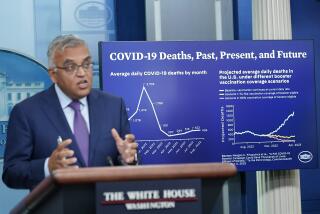

In a new report, researchers at Imperial College London said we may need to continue these behaviors until a vaccine becomes available. Experts say that’s probably 12 to 18 months down the road.

While it’s possible that these interventions could be relaxed earlier, they would have to be put back in place if case numbers were to rebound, the authors of the report said.

Dr. Jay Butler, deputy director for infectious disease at the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said there are many variables that will determine how long it will take for the pandemic to run its course. Still, he acknowledged that the most models suggest it will not abate for another year at least.

That forecast is hard to stomach. Can we really live in this heightened state of anxiety for the next 12 months?

Our brains are wired to plan for the future, and when that future becomes difficult to imagine, it can take a significant toll on our mental health, Holman said.

“If you sense that you don’t have a future, you don’t have hope,” she said.

It’s only natural that you’re obsessing about the coronavirus, but that anxiety is neither healthy nor necessary. Here’s why you should stop, and how to do it.

Holman’s research has found that when people experience traumatic events like fires or mass shootings, their perception of time slows down. In addition, they become so focused on the present that the past and future seem to slip away.

Her work also revealed that people who are less oriented toward the future also have a higher sense of distress that can make them become depressed or anxious.

But there is something that can help: Connecting with friends and family.

She found that people who received social support in the two months after 9/11 were much more future-oriented on the one-year anniversary of the event than those who did not.

“Staying connected is a way to stay grounded,” she said. “It keeps you from being pulled into a state of sheer anxiety.”

Vaile Wright, a director of clinical research at the American Psychological Assn., said that while we may not like this new reality we find ourselves in, we can learn to accept it as part of a process called “habituation.”

Wright describes habituation as an adaptive quality “because your body recognizes it can’t stay in a heightened sense of arousal forever.”

“You will start to adapt and it will become less arousing,” she said.

When and if that might happen, however, depends on each individual.

The benefit of habituation is that it allows people to redirect their emotional energy away from fighting reality — and toward managing it.

“If you accept that this is how it is going to be for a period of time, then you can use your resources for self-care and taking care of people in your life,” she said.

To make it through the coronavirus crisis, she also recommends focusing on the positives: That the vast majority of people recover from COVID-19, that some countries have managed to slow the virus’ spread, and that these painful social distancing measures are ultimately about protecting others who may be more vulnerable than we are.

“It is a very altruistic thing to do,” she said.

A guide to social distancing: When to stay home, when it’s OK to go out, and how to behave in public without putting yourself or others at risk.

Rheeda Walker, director of the Culture, Risk, and Resilience Lab at the University of Houston in Texas, said it is also important to be intentional about how you talk to yourself during this time of rapid change and uncertainty.

“Lets say you have kids at home,” she said. “On the one hand you can say, ‘I can’t get my job done with these little people in my house.’ Or you can say, “This is what it is, now how do I make this work.’”

It won’t be easy, she added, so don’t beat yourself up if your early attempts to adjust to life in a pandemic aren’t entirely smooth.

“We may have to experiment a bit,” Walker said. “Just because it doesn’t work doesn’t mean nothing is going to work, so you continue to experiment and figure out what works.”