NASA’s new Dragonfly mission will search for life on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon

NASA’s newest mission will send a giant flying drone to a world unlike any the space agency has visited before: Saturn’s methane-drenched moon, Titan.

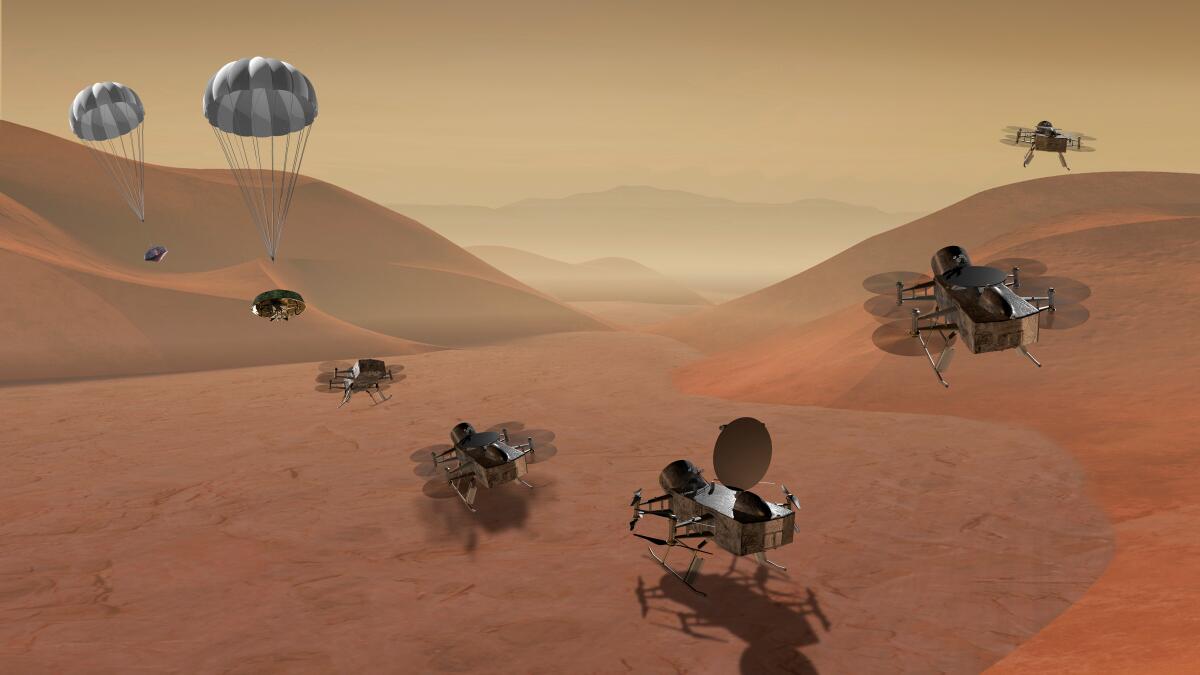

The Dragonfly spacecraft, set to launch in 2026 and reach its target in 2034, will be designed to fly more than 100 miles over the massive moon’s frigid terrain, sampling a wide array of environments that could offer new clues about the potential for life on other worlds — and the origins of life on our own.

“We are absolutely thrilled,” said planetary scientist Elizabeth Turtle, the principal investigator for the mission. Her project was selected over another proposal to collect samples from a comet.

Dragonfly will be roughly the size of a Mars rover, Turtle said. But instead of wheels or treads, it will be equipped with eight propellers and skids.

The drone-like craft will make dozens of stops on Saturn’s largest moon over the course of about 2 1/2 years, exploring dune fields and impact craters along the way. And its suite of cameras, drills and scientific instruments will probe the nature of the organic molecules that litter the mysterious surface.

Titan looms large among the solar system’s moons. It is second in size only to Jupiter’s moon Ganymede and is even a bit larger than the planet Mercury.

The orange haze of Titan’s thick atmosphere kept its surface mostly shrouded from sight, until the Cassini spacecraft and Huygens probe arrived in 2004. The two explorers brought many of Titan’s secrets to light, revealing a world whose lakes, rivers and canyons flowed with ethane and methane instead of water.

It’s “sort of like the liquefied natural gas that’s in your propane tank for your barbecue grill,” said Curt Niebur, lead program scientist for NASA’s New Frontiers program.

As sunlight breaks down these carbon-based molecules, the fragments can recombine to form all kinds of complex organic substances — some of which could potentially act as precursors for life.

Titan also appears to have a subsurface ocean made of liquid water, protected by a water-ice crust. This puts it in the company of ocean worlds like Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Jupiter’s moon Europa, both of which have been targeted as potential habitable environments for microbial life.

With a large reservoir of water, a wealth of organic compounds and an energy source in the form of the sun, Titan could even serve as a model for understanding the chemistry of early Earth, scientists said.

“Titan is just a perfect chemical laboratory to understand prebiotic chemistry — the chemistry that occurred before chemistry took the step to biology,” said Turtle, who is based at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md.

A drone made sense on Titan because its atmosphere is about four times as dense as Earth’s, but its gravity is only one-seventh as strong.

“Flying on Titan is actually easier than flying on Earth,” she said.

A number of the spacecraft’s cameras will be safely ensconced within Dragonfly’s body in order to protect them from the harsh environment. (Average temperatures on the moon’s surface hover at minus-290 degrees Fahrenheit.)

A pair of drills in the landing skids will gather samples from the surface and a mass spectrometer in its body will examine their chemistry. A seismometer will monitor Titan’s moonquakes.

With a nuclear power source similar to the one within NASA’s Mars rover Curiosity, Dragonfly could theoretically keep warm enough to work for about eight years, Niebur said.

“That’s the long limit,” he said.

Dragonfly is the fourth New Frontiers mission, following the New Horizons flyby of Pluto and Ultima Thule, the Juno satellite around Jupiter and the OSIRIS-Rex mission to the asteroid Bennu.

Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, drew parallels between Dragonfly and the transformative powers of the Apollo program that put the first humans on the moon nearly 50 years ago.

“We do these bold missions that change not only what we know but how we think [about] what’s possible,” Zurbuchen said.

“It’s the science that we want to do.”