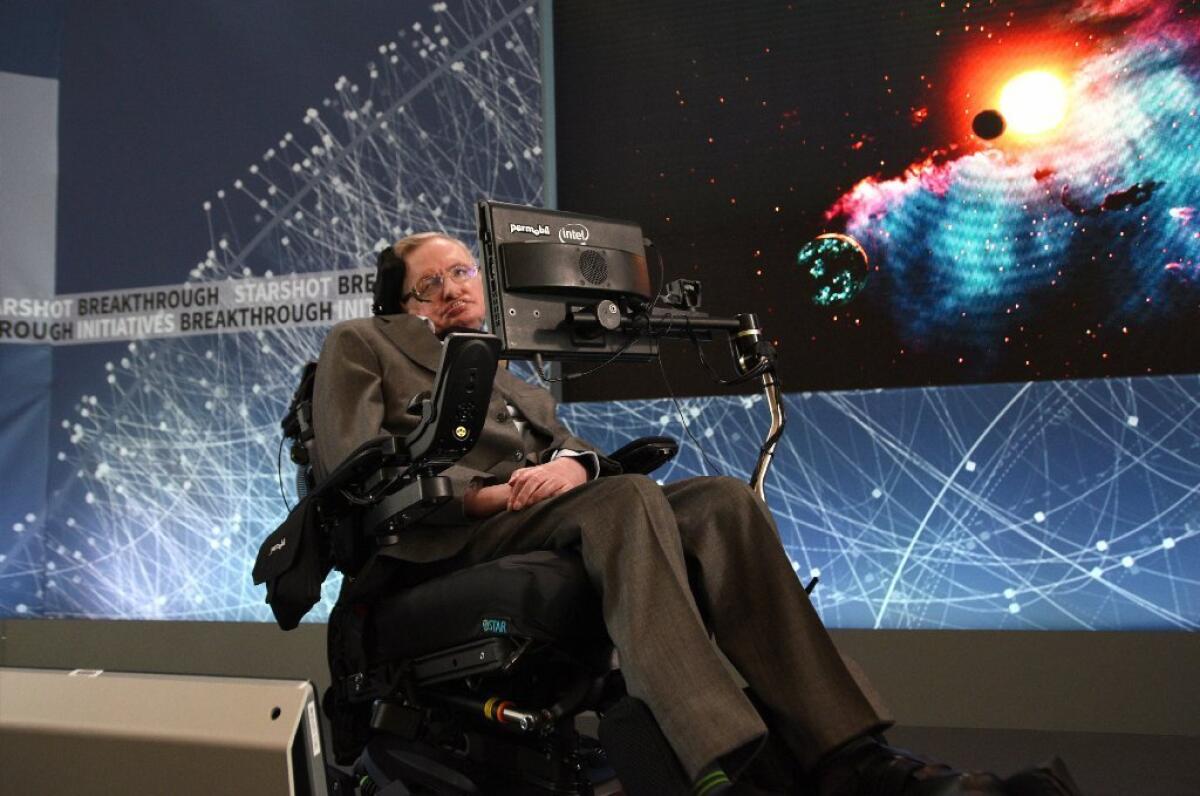

Starshot: Russian billionaire and Stephen Hawking want to use lasers to send tiny spacecraft to nearby star

Famed physicist Stephen Hawking is one of the researchers teaming up with Russian billionaire Yuri Milner on a $100-million effort to develop the technology to send spacecraft to the nearest star.

This is not your granddad’s moonshot. Russian billionaire Yuri Milner and physicist Stephen Hawking have announced Breakthrough Starshot, a $100-million initiative to develop spacecraft that would send probes all the way to Alpha Centauri, the nearest star system.

These nano-craft would have to travel roughly a thousand times faster than current spacecraft – and would also be much smaller, consisting of a light sail and a chip that could fit in your cellphone. That’s a big job for some tiny tech.

“Collectively we as humans are at a point in which, technologically, there’s at least one feasible path to getting to another star within our generation,” former NASA astronaut Mae Jemison said at a news briefing Tuesday at the One World Observatory in New York City. Jemison now leads the 100 Year Starship project, which fosters research into the necessary technology for interstellar travel.

Over the 20th and 21st centuries, humans have been sent as far as the moon and spacecraft have ventured much farther – to Mars, to Pluto and in the case of NASA’s Voyager spacecraft, into interstellar space. But even Voyager, traveling around 40,000 mph, has centuries to go before it enters the Oort Cloud ringing our solar system’s fringes – and tens of thousands of years more to emerge from it. Visiting the nearest star is another challenge entirely.

“Can we literally reach the stars?” Milner asked. “And can we do it in our lifetimes?”

Alpha Centauri sits about 4.37 light-years from Earth, or around 25 trillion miles away. This means that we are seeing the three-star system as it looked during the last election cycle, Milner pointed out.

If Voyager had left Earth when humans emerged from Africa many tens of thousands of years ago, he added, the craft would just be arriving at the nearest star today. Even at 40,000 mph, “space travel as we know it is slow,” he said.

The Starshot initiative seeks to develop a system that could beat those odds by flying at unprecedented speeds. This means putting the technology, including the camera, not on a giant space telescope but instead on a tiny chip. That device will be attached to an ultra-lightweight light sail – a surface that uses the pressure from light particles, or photons, to propel it along.

Some spacecraft, like NASA’s Kepler space telescope, already use the gentle pressure from photons to maneuver; light sails have been designed by many and even deployed in the Japanese spacecraft IKAROS. But the Starshot system would actually use many lasers to create a powerful beam that would hit these tiny, lightweight spacecraft, accelerating them to 20% of the speed of light.

At such speeds, it would take only a couple of decades to reach our next-door neighbor.

“Today is the day that space explorers have dreamed about: The stars are finally within our reach,” said Pete Worden, the initiative’s executive director and former head of NASA’s Ames Research Center.

Because these tiny spacecraft would be so small (and much cheaper than a behemoth like NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope), swarms of them could be sent out into space over time instead of just one, spreading the risk that any one of them might not make the journey.

There are myriad technological challenges to be understand and overcome before making this a reality, said Harvard physicist Avi Loeb, chair of the initiative’s advisory committee. But the payoff – to be able to observe a star and its planets at a close distance, even with rudimentary tools – would be well worth it.

“As all of us know, there is a big difference between exploring physically some other regions of space and looking at them from a distance,” Loeb said. “Columbus aimed at the East Indies, but he found the New World. Starshot is aiming to image exoplanets near Alpha Centauri; we might find other things.”

First, he added, the nano-crafts would swing by targets in our own solar system; a trip to Pluto at about 20% of light speed would take roughly three days instead of 9.5 years – the length of time it took NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft to reach the demoted dwarf planet.

Retired physicist Freeman Dyson, who worked in the 1960s on Project Orion (which Milner called the first serious proposal for interstellar travel), sounded a cautionary note. He pointed out that NASA’s efforts to put a man on the moon did not build in natural steps to continue forging ahead.

“We shouldn’t say right away that we’re going to Alpha Centauri,” Dyson said. “That’s the same mistake that was made with the Apollo program.... It turned out to be kind of a dead end for that reason. Once we got to the moon and got back, somehow the steam had gone out of it.”

Instead, he said, programs like Apollo should have framed the endeavour not as a one-shot mission but as a sustainable program of exploration.

Jemison pointed to the need not just to recruit talented scientists, engineers and technicians, but also to have policymakers create an environment that fosters more international collaboration.

“How do we get an opportunity to see ourselves as Earthlings?” she said.

Follow @aminawrite on Twitter for more science news and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.