More than 90% of people who overdosed on prescription painkillers can still get refills, study says

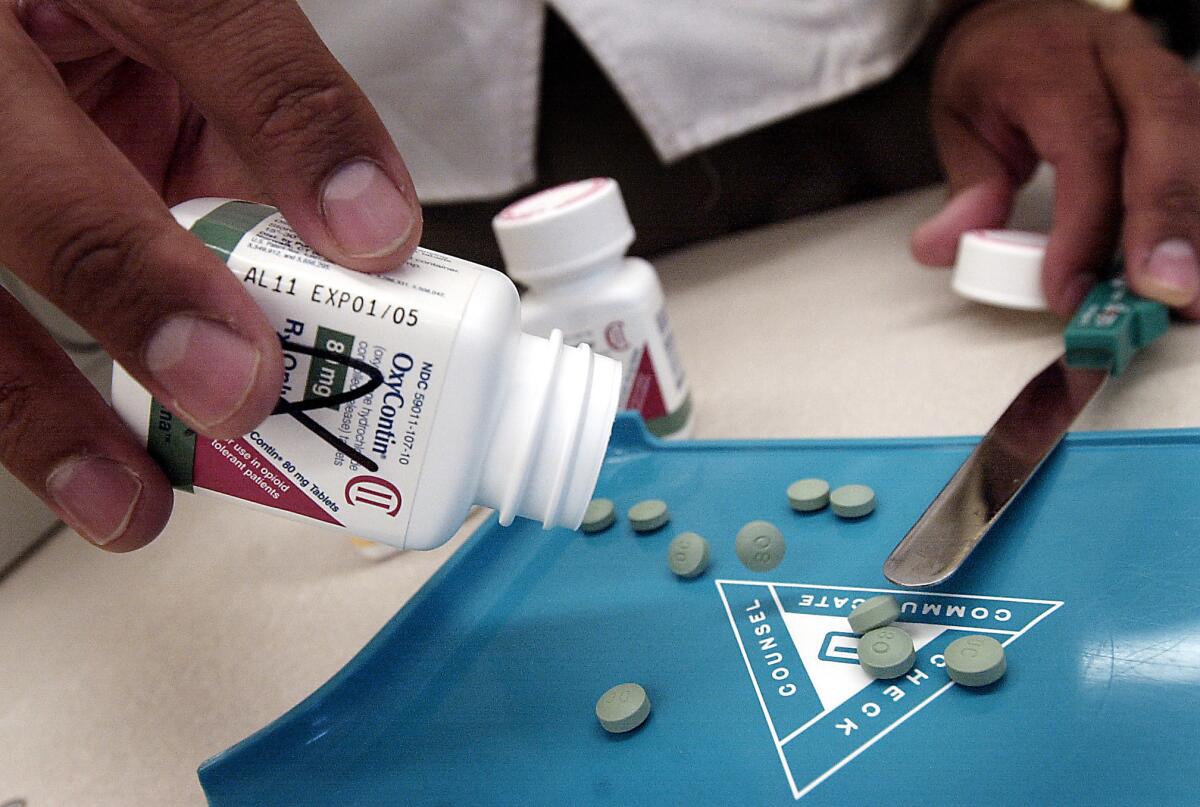

A pharmacist displays tablets of the prescription painkiller OxyContin. A new study finds that 91% of people who had a nonfatal overdose of opioid painkillers like OxyContin continue to get refills from a doctor.

Even after overdosing on opioid medications, more than nine out of 10 patients continued to get prescriptions for the powerful painkillers, according to a new study. As a result, some went on to suffer another overdose.

The findings, published Monday in Annals of Internal Medicine, are “highly concerning,” the study authors wrote. The overdoses examined in the report were serious enough to send patients to emergency rooms or get them admitted to hospitals, so they should not have escaped their doctors’ attention.

But that may be exactly what happened, the researchers surmised. In 70% of the cases, the physician who prescribed opioid painkillers after the overdose was the same as the one who wrote the prescription before the overdose. That tends to support the idea that the prescribers simply weren’t aware that anything had gone awry.

“Prescribing guidelines … clearly state that misuse of opioids and adverse effects are compelling reasons to discontinue opioids,” the study authors wrote. Presumably, if doctors knew about the overdoses, they would have thought twice before authorizing their refills.

“Some prescribers may have been unaware that the opioid overdose occurred,” wrote the authors, led by Dr. Marc Larochelle, who studies addiction issues at the Boston University School of Medicine.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

With 16,651 deaths blamed on prescription painkillers in 2010, Larochelle and his colleagues were on the lookout for ways to identify patients at heightened risk for a fatal overdose. A nonfatal overdose seemed a likely candidate.

So they used a nationwide medical database to identify 2,848 people in the U.S. who had an opioid overdose that was bad enough to send them to the hospital but not serious enough to kill them. All of these patients were on long-term opioid therapy to treat pain for diseases other than cancer. Their prescription painkillers included morphine, codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone and fentanyl.

The average age of these patients was 44, and 60% of them were women. In addition, 46% of patients were taking doses of opioids that were high enough to be considered “large” (as opposed to “low” or “moderate”) and 41% of them were known to have a drug use disorder, as documented by their medical insurance claims.

But the main thing the researchers wanted to know was whether these patients continued to get prescription painkillers after having a serious overdose. The answer was clear: They did.

On the 30th day after their overdose, about one-third of the patients in the study had prescriptions that delivered “high daily opioid dosages,” the researchers found. Over the next 30 days after that, about 70% of the patients had an “active opioid prescription” on any given day.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

Overall, a whopping 91% of the patients got at least one opioid prescription sometime after their nonfatal overdose. A typical patient was tracked for 299 days, but some were tracked for well over a year.

In general, patients stayed in the same dosage category (low, moderate or large) before and after their overdose, the researchers found. To the extent that dosages changed, they tended to get smaller. Even so, 7% of the patients who had already suffered one opioid-related overdose went on to suffer a second overdose while they were still in the study pool.

Most patients wound up leaving the pool because they switched their health plan (including those who enrolled in Medicare). Still, the researchers were able to calculate that 17% of patients getting high doses of opioids were likely to have a repeat overdose within two years. So were 15% of those getting moderate doses of opioids and 9% of those with low doses of the painkillers.

Despite these risks, there could be some legitimate reasons to keep patients on prescription opioids even after an overdose, the study authors wrote. For instance, if a patient didn’t abuse the drug but merely followed instructions from a doctor that turned out to be unsafe, perhaps the best thing to do is modify the prescription. Or a doctor may decide that although the risk of another overdose is bad, letting a patient’s pain go untreated would be even worse – especially if the patient would be tempted to get relief from an illicit painkiller.

Still, it seems unlikely that such explanations would apply to all of the patients who continued to get opioid prescriptions from the same doctor before and after their overdose. Ignorance on the part of prescribers likely played a role in at least some of these cases, the researchers suggested.

“We are not aware of procedures to ensure provider notification after a nonfatal overdose,” they wrote.

But that could change. Large health plans might be able to connect the dots by linking claims for opioid prescriptions and overdose treatment, the researchers wrote.

In addition, 49 states have prescription-monitoring programs in place. These programs make it possible for hospitals that treat overdose patients to reach out to the doctors who prescribed the painkillers in the first place and let them know what happened.

The study was funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE SCIENCE NEWS

How NORAD became the world’s official Santa-tracker

First full moon on Christmas since 1977! How to see it

Fireball seen passing over Southern California is identified as Russian space junk