A rare great ape, a 130-foot-tall tree and an extinct marsupial lion make the Top 10 New Species list for 2018

The highest branches of a Brazilian forest. The permanent darkness of a cave in China. The deepest place on Earth.

Life has carved niches for itself in the most extreme and stunning habitats. As a result, it has taken on surprising — and just plain weird — physical attributes and behaviors.

In celebration of this biodiversity, the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry has compiled a list of the Top 10 new species that were described by science in the previous year. (Read the 2017 list here.)

“I’m constantly amazed at how many new species show up and the range of things that are discovered,” Quentin Wheeler, the college’s president and founding director of the International Institute for Species Exploration, said in a statement.

This year’s list includes a rare great ape, a hitchhiking beetle, an extinct omnivorous marsupial lion and many species that are critically endangered. As humans alter habitats and contribute to global climate change, species are going extinct at a faster rate than we can name them.

“If we don't find them, [these species] will be lost forever,” Wheeler said. “And yet they can teach us so much about the intricacies of ecosystems and the details of evolutionary history. Each of them has found a way to survive against the odds of changing competition, climate and environmental conditions.”

Here are the creatures that made the 2018 Top 10 list:

A mysterious single-celled organism

Ancoracysta twista

Location: Unknown

This microscopic marvel is unlike anything scientists have ever seen.

Researchers discovered the protist living on a brain coral in a tropical aquarium at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego. The organism propels itself with a whip-like tail, called a flagella, and uses unusual harpoon-like structures to stun and consume other protists. Because scientists found the species in captivity, they can’t be sure of its geographic origins in the wild.

The cell’s genetic origins also puzzled its discoverers. A. twista does not fit with any known group of organisms. Instead, it appears to belong to an early lineage of eukaryote that was previously unknown.

Brazil’s lonely giants

Dinizia jueirana-facao

Location: Brazil

These massive trees stand up to 130 feet above the canopy of Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, producing woody fruits that grow over a foot long. A member of the legume family, this 62-ton giant is found only in and just outside the Reserva Natural Vale in Espirito Santo, Brazil. With just 25 known trees, the species is considered critically endangered.

The tree’s sister species, D. excelsa, was discovered almost 100 years ago. In September, scientists described the smaller D. jueirana-facao as a distinct species.

The Atlantic Forest — which is home to more than half of the country’s threatened animal species — may be endangered itself. The region once covered 330 million acres, but humans have since cleared 85% of the now-fragmented forest.

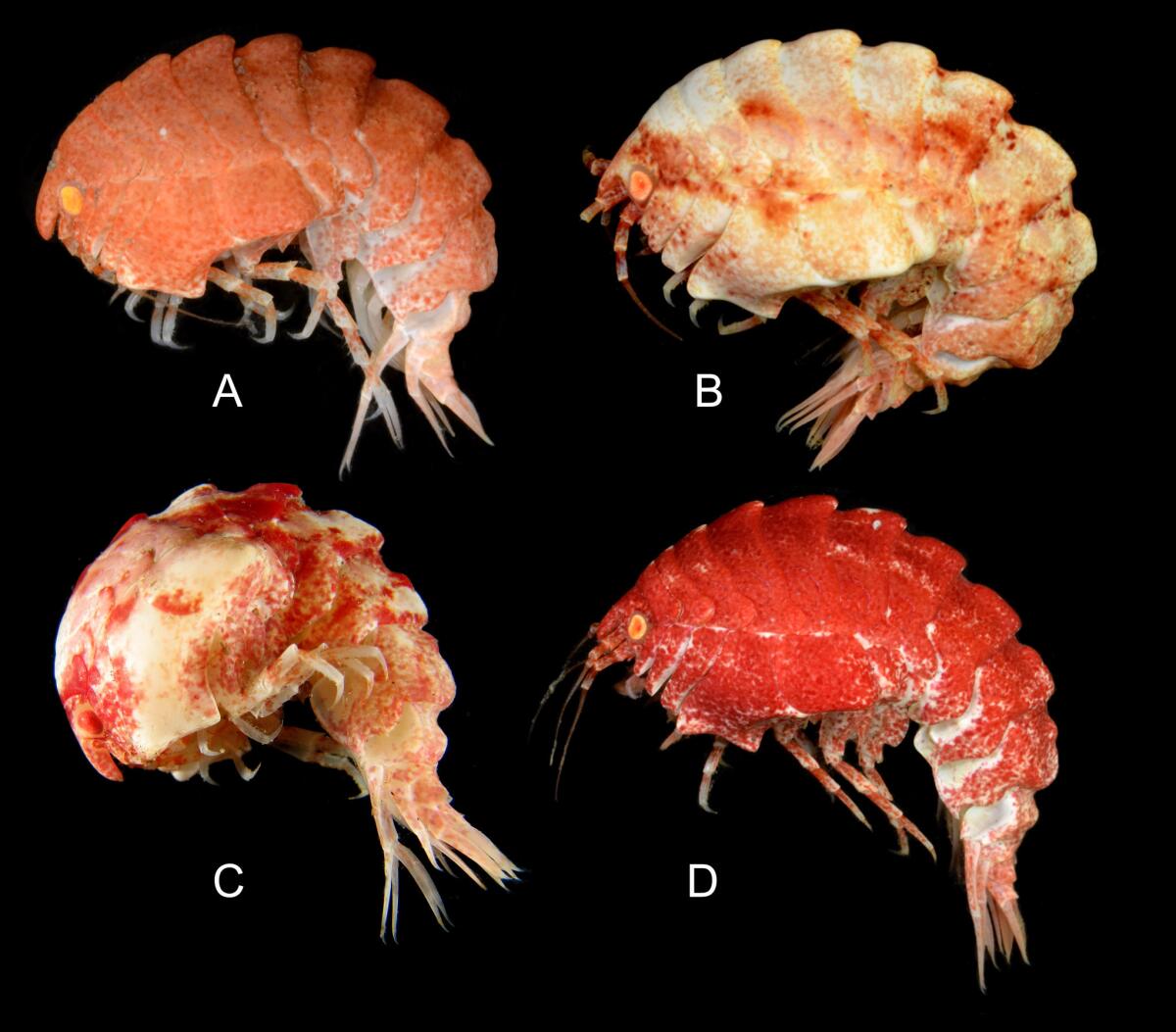

A hunchbacked shrimp

Epimeria quasimodo

Location: Southern Ocean

Last year, scientists discovered 26 new species of tiny crustaceans in the Southern Ocean off Antarctica. These amphipods are famous for their bright colors, spines and variety; some live as free-swimming predators and others stay put and feed by filtration. But one species stood out for its humped back, which reminded scientists of Quasimodo of Victor Hugo’s “The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.” E. quasimodo is about 2 inches long.

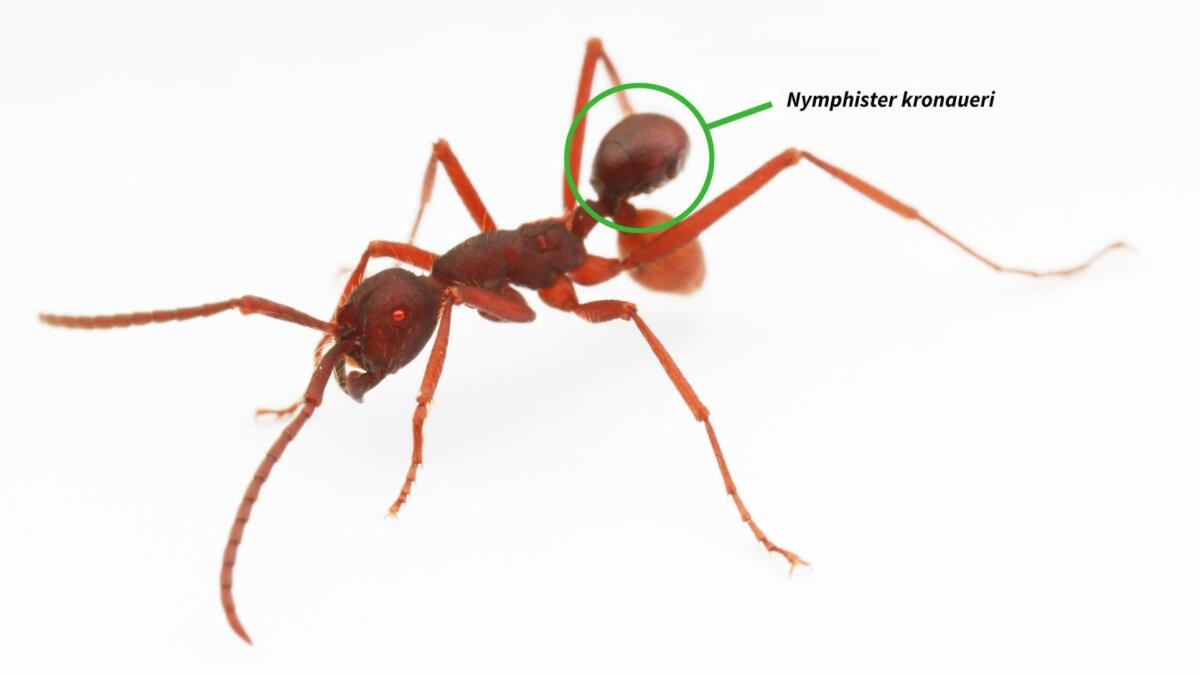

A hitchhiking beetle

Nymphister kronaueri

Location: Costa Rica

Plenty of creatures use mimicry and camouflage to great effect, but this tiny beetle takes it to another level.

Nymphister kronaueri evolved a set of traits that allow it to live among a particular species of army ant in Costa Rica. Army ants are nomadic, spending a few weeks in one place before migrating for about three weeks to new territory. When the ants move, so must the beetles. That’s when their mimicry comes into play.

The beetle, only 1.5 millimeters long, is shaped, sized and colored just like the abdomen of a worker ant. N. kronaueri uses its tiny mandibles to clamp down on its host’s abdomen as the ants embark on their journey. This makes it look like the ant has two abdomens. These myrmecophiles, or ant-lovers, likely use similar chemical signals as the host ants to avoid detection.

A new species of great ape

Pongo tapanuliensis

Location: Sumatra, Indonesia

The great ape family welcomed an eighth member in 2017: Tapanuli orangutans.

In 2013, researchers compared the skull of an adult male Sumatran orangutan killed by humans to 34 others. Last year, they announced that they had found enough subtle differences to convince themselves that this individual belonged to a distinct species. Tapanulis, named for the region of the island in which they’re found, live in the southern range limit of Sumatran orangutans. An estimated 800 individuals exist in a small, fragmented habitat.

About 674,000 years ago, orangutans on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo split into separate species. However, the Sumatran species diverged about 3.38 million years ago. In addition to three species of orangutan, the other living species of great ape are western and eastern gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos and, of course, humans.

The deepest fish in the sea

Pseudoliparis swirei

Location: Western Pacific Ocean

Plenty of surprises still lurk in the deep ocean.

Researchers exploring the Mariana Trench, the deepest place on Earth, found large numbers of weird, tadpole-like fish swarming their mackerel-baited traps. This translucent snailfish was recorded 5 miles below the surface of the ocean, making it the deepest-dwelling fish in the world. Scientists believe the 5-mile mark represents a physiological limit below which most fish can’t survive.

Despite measuring just 4 inches in length, the Mariana snailfish is the top predator in its ocean-floor habitat, the researchers observed.

A fungal-feeding flower

Sciaphila sugimotoi

Location: Ishigaki Island, Japan

Among Japan’s well-documented flora, one unusual flower eluded science until now.

In September and October, Sciaphila sugimotoi produces delicate magenta blossoms in only two locations in Ishigaki’s humid forest. The plant lives symbiotically with a fungus, which provides it with the energy it needs to survive. That’s in contrast to most other plants, which derive energy from the sun using photosynthesis.

About 50 plants make up the critically endangered species, researchers suggest.

A bacterial eruption

Thiolava veneris

Location: Canary Islands

In 2011, the underwater volcano Tagoro erupted and wiped out much of the ecosystem off the coast of El Hierro in the Canary Islands. Three years later, a strange new bacteria was the first organism to re-colonize the area.

Dubbed “Venus’s hair” for its long, hair-like structures, the proteobacteria grew to almost half an acre in size and covered Tagoro’s summit with a massive white mat. The colony, scientists suggest, represents the start of a new ecosystem 430 feet below the surface of the ocean.

A marsupial lion

Wakaleo schouteni

Location: Australia

About 23 million years ago, a lion the size of a Siberian husky roamed the Australian forest. This marsupial ate both meat and plants, and spent part of its days up in the trees.

Fossilized remains of the creature were unearthed in the Riversleigh World Heritage Area in Queensland. W. schouteni was one of two marsupial lions that existed toward the end of the late Oligocene Epoch 25 million years ago. In the subsequent Miocene, species of the genus Wakaleo, or little lions, grew larger in an evolutionary chain reaction: Prey animals got bigger as plant life changed in response to a drying and cooling continent.

A cave-dwelling beetle

Xuedytes bellus

Location: China

Du’an Karst, a system of limestone caves in China’s Guangxi province, is a veritable kingdom of cave-dwelling ground beetles.

To date, more than 130 species have been discovered in the region, the latest being Xuedytes bellus. Researchers marvel at how “extremely cave-adapted” the beetle appears, with its dramatically long head and neck and slender body.

Beetles that evolve in the darkness of caves often take on a similar set of characteristics, including narrow bodies, spider-like appendages and loss of wings, eyes and color.