NASA declares end to Opportunity’s unequaled Mars mission: ‘We did love this rover’

The Opportunity rover lasted 15 years and traversed more than 28 miles on the surface of Mars. A dust storm lead to a loss of communication with it.

Opportunity, the intrepid NASA rover that spent 15 years on Mars climbing in and out of craters to gather evidence of the planet’s watery past, has been brought down by tiny particles of dust.

It’s a humble ending for a machine that survived a 300-million-mile journey through space, executed a hole-in-one landing, and set a record by driving more than 28 extraterrestrial miles.

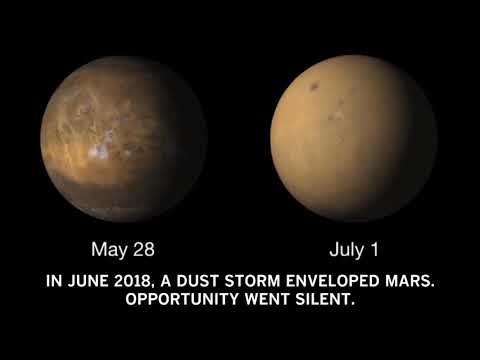

Opportunity’s last transmission to Earth occurred on June 10 amid an epic Martian dust storm. Still, NASA engineers remained hopeful that when the dust settled, the rover would recharge its solar-powered batteries and resume its superlative mission.

Until Wednesday.

After sending more than 1,000 unanswered commands to the Smart-car-sized vehicle, NASA officials announced that Opportunity’s mission had officially come to an end.

“With a sense of deep appreciation and gratitude, I declare the Opportunity mission is complete,” Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, told a crowd gathered at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge, where the mission was built and managed.

Steve Squyres, a planetary scientist at Cornell University and the principal investigator for NASA’s Mars Exploration Rover project, said Opportunity went out like a true veteran.

“It’s like an old-time explorer who sets out over the horizon in the midst of a storm and you never hear from them again,” he said.

Engineers can’t say whether Opportunity’s solar panels are so covered with dust that they can no longer function, or if the rover became so cold in the midst of the dust storm that something inside it snapped — perhaps a joint, a cable or some other critical component.

“It’s likely that we’ll never know,” said John Callas, project manager of the Mars Exploration Rover mission. “That’s one of the challenges of space exploration.”

Like its twin rover, Spirit, Opportunity was originally designed to last just three months and travel 1,100 yards in the harsh Martian environment.

Instead, it operated more than 60 times longer than planned and sent back more than 17,000 images of the red planet.

“Opportunity has allowed Mars to become a familiar place to us,” Callas said. “For the past 14½ years, a team of people has gone to work on Mars every day. Opportunity made them Martians.”

The two rovers were sent to Mars in the summer of 2003 to look for signs of water in the planet’s distant past. Data from NASA’s Mars orbiters strongly suggested that water once flowed on the Martian surface, but Spirit and Opportunity were the first to tackle that question from the ground, mission planners said.

Together, they showed that Mars was once a habitable planet — much warmer, wetter and Earth-like than it is today.

“Opportunity and Spirit were trying to read the story in the rocks,” Squyres said.

The two robots touched down on their new home in January 2004, but they were sent to opposite sides of the planet so they could explore very different environments.

Spirit, which developed a reputation as a problem child even before it left Earth, landed in Gusev Crater. That location turned out to be a rocky plane of lava, covered in rubble and difficult to navigate.

It spent six days driving more than a mile to Columbia Hills before it began to make crucial finds about Mars’ potential for harboring life.

Opportunity, on the other hand, started its Martian journey in Meridiani Planum, a possible former lake bed in a giant impact crater. It rolled to a stop in Eagle Crater just 32 feet from where it would make one of the biggest discoveries of the mission: hematite, a mineral that typically forms in water.

“Spirit had to work for everything,” Squyres said. “Opportunity was the lucky one.”

The two rovers were equipped with a suite of tools that allowed them to serve as virtual geologists.

They each had high-resolution color cameras that gave them the equivalent of 20/20 vision. Each had a robotic arm with a shoulder, elbow and wrist, allowing them to reach out and examine anything that looked interesting.

Using an infrared spectrometer, they scanned the Martian landscape for rocks and soil that contained minerals that form in water. A microscopic imager gave them the ability to look at the texture of a rock up close and at a very fine scale.

They also had two spectrometers that enabled them to determine the mineral composition of stones and boulders, and a little diamond-tipped grinding tool to chip away at the surface of a rock and see what lay beneath.

“It was essentially a robotic geologist with eyes, a hand lens and a rock hammer,” Squyres said. “The difference is that instead of taking something interesting back to the lab, we took our laboratory with us.”

Armed with this arsenal, Opportunity quickly found strong evidence that its original landing site once contained a large body of salty water. The physical appearance of the rocks and the discovery that many of them contained minerals that usually form in watery conditions revealed that the dry and dusty planet did indeed have a secret, wetter past.

Later, mission planners drove the rover across 20 miles of bumpy Martian terrain to an ancient crater named Endeavour. There it encountered even older rocks and found veins of a mineral that scientists believed to be gypsum.

“This tells a slam-dunk story that water flowed through underground fractures in the rock,” Squyres said at the time.

Although its primary job was to look for evidence of water, Opportunity also made time for some sightseeing. It sent back images of a towering dust devil sweeping across the landscape, took photos of comet Siding Spring as it streaked through the Martian sky, and became the first robot to spot a meteorite on another planet.

It also set the record for the most miles driven on an extraterrestrial surface. Its final odometer reading is 28.06 miles, which puts it nearly two miles past a marathon.

NASA officials said the Mars Exploration Rover mission introduced a new model for studying other planets.

“When we think about planetary science now, we assume we want mobility,” said Lori Glaze, acting director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division. “We want to roll up to rocks, bang them a little, scratch them and understand their chemistry. It was these two rovers that set that new paradigm.”

Even when it was still roving, Opportunity was in declining health.

Two of its front wheels were no longer working, and so it had to traverse Mars using the equivalent of two-wheel drive. The joints on its robotic arm had started to deteriorate. Like many old-timers, its memory was starting to go.

But it was still exploring.

When the dust storm hit in late May, Opportunity was on its way to examine an inner wall of Endeavour Crater that looked like it might have been carved by the flow of water. The rover was about halfway down the slope of the crater when the skies filled with deadly dust.

“There is always some tantalizing thing you just can’t get to,” Squyres said. “That is the nature of discovery.”

Spirit’s exploration of Mars came to an end in March 2010, about a year after its wheels broke through the thin crust of Gusev Crater and got hopelessly stuck in the powdery sand that lay beneath. Mission planners originally tried to convert the rover to an immobile science observatory, but eventually Spirit put itself into a hibernation mode from which it never awoke.

Spirit was officially declared dead in May 2011. “I am very depressed,” John Wright, a member of the rover’s driving team, said at the time. “Spirit has been my baby for seven years now. We were waiting and waiting to hear something, and never did.”

Now, scientists and engineers who work on Opportunity are experiencing a similar sense of loss, despite the rover’s old age.

“It’s little comfort when you lose a loved one to say they had a full life,” Callas said. “It doesn’t address the sadness.”

People who work on long-lived space missions often have feelings of affection for the mechanical space explorers they interact with every day.

But Opportunity and Spirit — with their arms and their eyes, the wheels that allowed them to traverse the Martian surface, and their relatively petite size — were especially easy to anthropomorphize.

Callas described Opportunity’s personality as “dutiful, accomplished, intrepid, recalcitrant and sometimes funny.”

“This is a machine that we have invested with human characteristics and our own human emotions,” Callas said. “We did love this rover. We do love this rover.”

Opportunity is survived on the Martian surface by NASA’s Curiosity rover and the InSight lander, and in the Martian sky by NASA’s Mars Odyssey, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and MAVEN spacecraft. A future rover mission known as Mars 2020 is scheduled to launch next year and join the others on the red planet in 2021.

“Mars is the only planet that is inhabited by robots, and I think it is going to remain that way for some time to come,” Squyres said. “But what we did lose is one of our real pioneers.”

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.