Lung cancer screening works better when individual risk factors are taken into account, study says

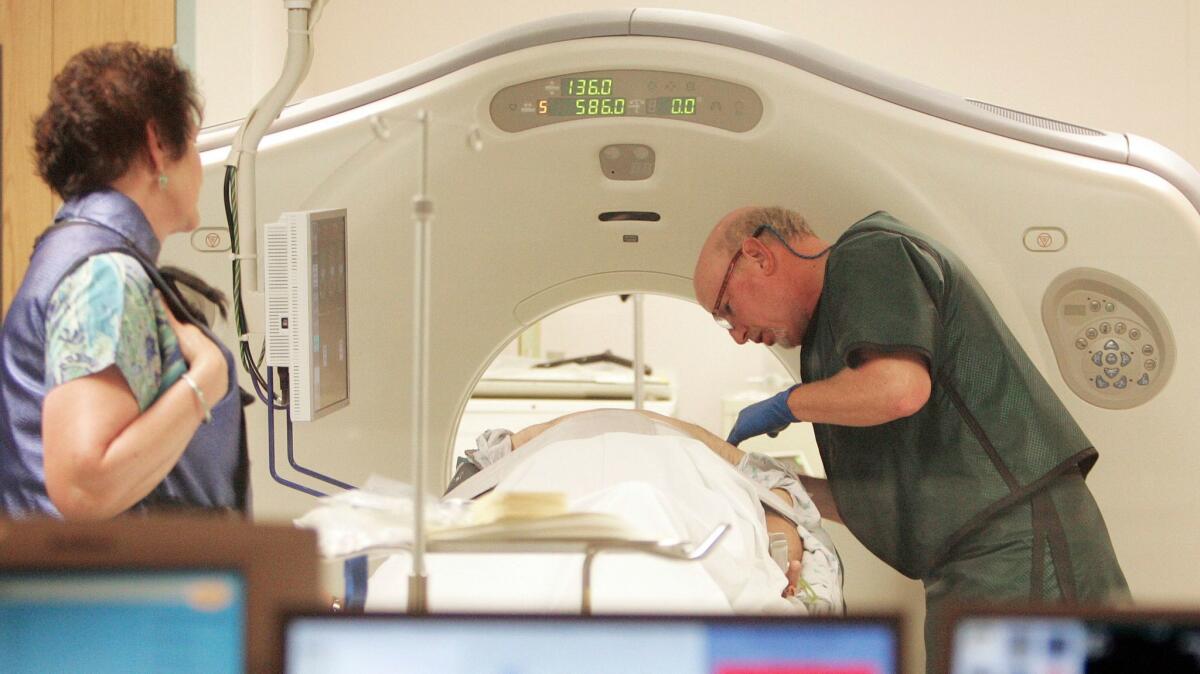

New research estimates that in a single year, some 5,000 lung cancer deaths might be averted if some former smokers who don’t currently qualify for lung-cancer screening were to get a computed tomography scan capable of detecting malignancy.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which lays down criteria for most cancer-screening detection methods, recommended in 2013 that lung-cancer screening should be limited to current or former smokers aged 55-to-80 with a 30-pack-year smoking history who’ve smoked within the past 15 years. A pack year is a year in which someone smoked an average of at least a pack of cigarettes per day. Private insurers, as well as Medicare and Medicaid, largely follow the task force’s criteria in deciding whose cancer screening they will pay for.

But in an analysis published this week in the Annals of Internal Medicine, scientists from the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society suggest that it’s time to broaden those criteria. They suggest instead that a more life-saving approach would end up screening some smokers with history of 20-to-29 pack-years but who also have personal risk for lung cancer that is higher than usual.

The group’s finding comes at a time when the number of Americans eligible for lung cancer screening under the task force criteria is falling fast. As the ranks of active smokers fall and more former smokers gain distance on their last quit date, the number of Americans eligible for lung-cancer screening has dropped from 9.5 million in 2010 to 8 million in 2015.

But among people who quit longer than 15 years ago, or who were not among the heaviest of heavy smokers, some still run a higher-than-average risk of developing — and dying from — lung cancer. Risk factors that increase an individual’s likelihood of doing so include a family history of lung cancer, obesity and a past diagnosis of emphysema. A person’s sex, race and level of education also factor into the calculation, with women, African-Americans and Asian-Americans, as well as those who completed less education, at greater risk.

The concern, when broadening the population of people screened for a cancer, is that people with cancers that never would have killed them will get results suggesting the need for more biopsies, more procedures and aggressive treatment. But the authors of the latest study said that there is room for expansion before that happens. Screening smokers and ex-smokers whose personal and family histories drive up their lung cancer risk will find, at an early stage, more lesions and nodules that would become deadly if left unchecked, they concluded.

Using 2015 statistics, the new analysis suggests that screening a broader population of current and former smokers could save 5,000 from dying prematurely due to lung cancer.

An economic analysis of the proposal offers a key qualification though. While broader screening criteria would pick up more deadly cancers, it’s not clear that it would give the overall group of screened patients significantly longer, or better, lives.

In a study published also published this week in Annals, researchers from Tufts Medical Center suggest, in effect, that broader screening will often find lung cancer in patients whose lung function and general health has already been compromised. Finding these patients’ tumors earlier, they found, will bring “attenuated and modest” gains in their lifespans.

And because expanding the population always brings many in for screening who never needed it in the first place, the cost-effectiveness of such an expansion is not great. Still, they found the marginal cost to be below the threshold sometimes mentioned as a reasonable standard for justifying a given health service.

In a related editorial, however, experts note that broadening the criteria for those who should have their lungs screened is a distant concern in a time and place where only a tiny fraction of those already eligible are getting screened. Nearly 7 million Americans are eligible under the existing recommendations. But an analysis of claims made in 2017 suggests that just 74,000 people got the screening.

Given how deadly lung cancer can be, and the “anemic pace” at which CT lung cancer screens are being performed, “the more pressing concern is why people, regardless of how their eligibility is defined, are not receiving the test,” wrote Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s Dr. Angela K. Green and Dr. Peter Bach.

MORE IN SCIENCE

11 science stories we’re looking forward to in 2018

Autism spectrum disorders appear to have stabilized among U.S. kids and teens

Do psychiatrists have any business talking about President Trump’s mental health?