Real-world doctors fact-check Dr. Oz, and the results aren’t pretty

What do real-world doctors have to say about the advice dispensed on “The Dr. Oz Show”? Less than one-third of it can be backed up by even modest medical evidence.

If that sounds alarming, consider this: Nearly 4 in 10 of the assertions made on the hit show appear to be made on the basis of no evidence at all.

The researchers who took it upon themselves to fact-check Dr. Oz and his on-air guests were able to find legitimate studies related to another 11% of the recommendations made on the show. However, in these cases, the recommendations ran counter to the medical literature.

“Consumers should be skeptical about any recommendations provided on television medical talk shows,” the researchers wrote in a study published this week in BMJ. “Viewers need to realize that the recommendations may not be supported by higher evidence or presented with enough balanced information to adequately inform decision making.”

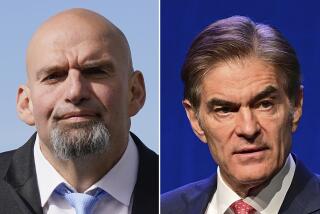

Critics of Dr. Mehmet Oz, an accomplished cardiac surgeon with degrees from two Ivy League universities, complain that his show is little more than an hour-long infomercial for weight-loss fads like green coffee bean extract. (The Federal Trade Commission has sued the company that hawks this dubious product.) A spokesman for the Center for Inquiry accused him of selling “snake oil.” In June, a Senate subcommittee took him to task for telling his viewers (who number 2.9 million on any given day) things like: “I’ve got the No. 1 miracle in a bottle to burn your fat. It’s raspberry ketones.”

“I don’t get why you need to say this stuff because you know it’s not true,” Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.) said during the hearing.

A large group of physicians, pharmacists and other researchers from Canada had their own questions about programs like “The Dr. Oz Show.” So they set out to see whether the “skepticism and criticism from medical professionals” was warranted.

The Canadians focused on “The Dr. Oz Show” and “The Doctors,” another daily talk show that averages 2.3 million viewers per day. After watching two episodes of each program, they hypothesized that only half of the claims made on the shows could be supported with actual evidence. They also calculated that they would need to review 158 specific recommendations to see whether their hypothesis was correct.

Lucky for them, the shows are rife with recommendations -- 12 in a typical episode of “The Dr. Oz Show” and 11 in an episode of “The Doctors.” So members of the research team watched 40 episodes of each show, which were randomly selected among all the episodes that aired in the first five months of 2013.

They found that 32% of the 479 recommendations made on “The Dr. Oz Show,” either by the host or his guests, fell under the heading of “general medical advice.” Another 25% of the claims were about diet (i.e., foods that boost the immune system) and 18% were about weight loss.

On “The Doctors,” 66% of the 445 recommendations were about “general medical advice,” 9% were about diet and 8% were about weight loss. (Other categories included exercise, alternative therapies and cosmetics.)

Among all of these recommendations, the researchers randomly selected 80 from each show and looked to see what evidence, if any, could back them up. Two team members conducted independent searches, spending up to an hour on each one. “In an attempt to be as fair as possible” to the shows, they wrote, they “used a relatively broad definition of support.”

And yet only 21% of the recommendations on “The Dr. Oz Show” could be supported by what the researchers considered “believable” evidence. Another 11% were supported by “somewhat believable” evidence.

The recommendations made on “The Doctors” were more credible -- 32.5% were supported by “believable” evidence and another 20% were backed by “somewhat believable” evidence, the researchers found.

Good or so-so evidence contradicted 11% of the claims made on “Dr. Oz” and 13% of the claims made on “The Doctors.”

The researchers also noted that for both shows combined, 40% of the recommendations mentioned a specific benefit of the intervention being touted. The size of the benefit was discussed in fewer than 20% of cases, possible harms or side effects came up less than 10% of the time, and potential conflicts of interest were mentioned in less than 1% of cases.

Neither Oz nor the team behind “The Doctors” could be reached for comment about the study’s conclusions.

The whole exercise left the researchers to ponder “whether we should expect medical talk shows to provide more than entertainment.”

For real medical news, follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.