Cholesterol is back on the menu in new federal dietary guidelines

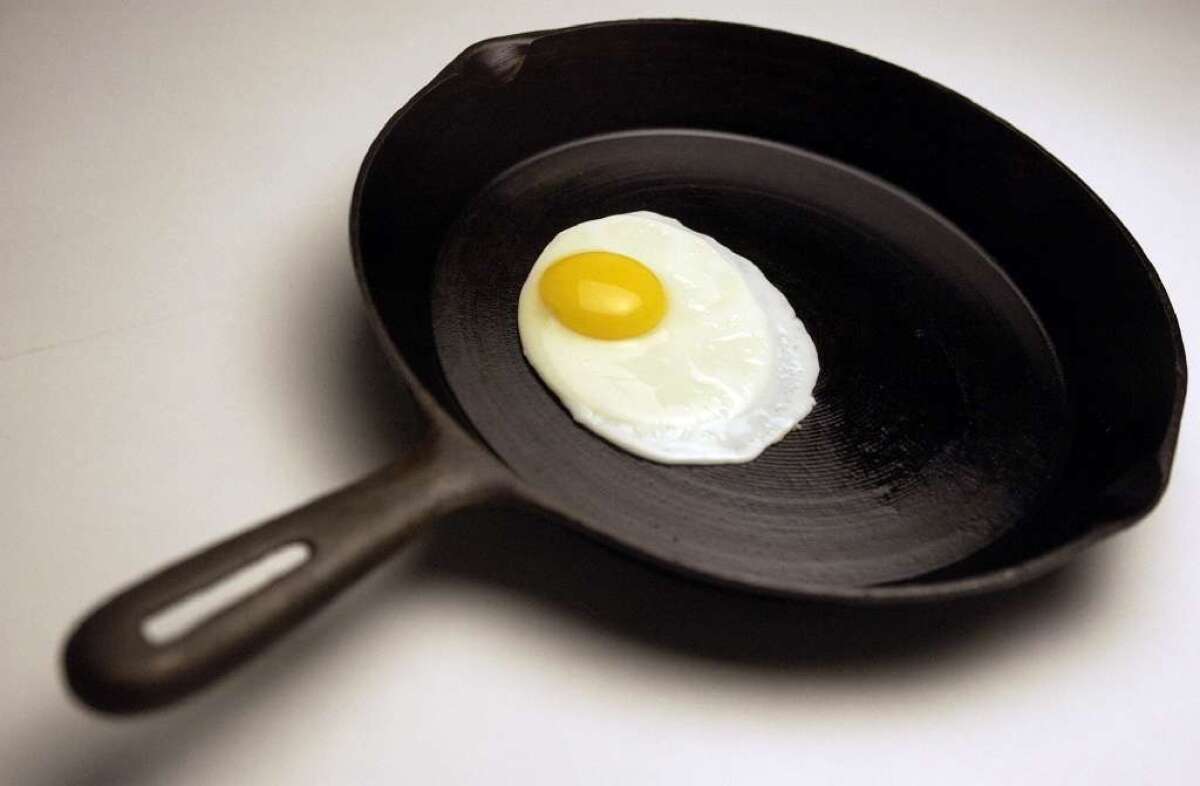

Go ahead and make that omelet. A new draft of the federal government’s healthy eating guidelines is poised to scramble some long-standing advice on cholesterol-rich foods.

Nutrition and public health experts advising the federal government recommended Thursday that cholesterol no longer be labeled a “nutrient of concern” — a designation that for decades has prompted health-conscious Americans to avoid eggs and other foods that are high in the fat-like substance.

The new advice appeared in the fine print of a scientific report prepared for the secretaries of Agriculture and Health and Human Services. It is widely expected to be adopted by the panel that will update the government’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans later this year.

For the first time, the advisory panel also gave Americans a thumbs-up on moderate coffee consumption. The committee said that daily caffeine intake equivalent to three to five cups of coffee is not only safe, but appears to reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in adults. Caffeine may even protect against Parkinson’s disease, the evidence suggests. (So have some coffee with those eggs.)

The report also breaks new ground in considering the environmental impact of American diets, noting that compared with average American eating patterns, a more healthful diet with fewer animal products and more plant-based foods — including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, seeds and legumes — would generate fewer greenhouse gas emissions and use up less land, water and energy.

The Dietary Guidelines set nutritional standards for state and federal programs such as school lunches, food stamps, and programs benefiting children and pregnant women; they will be the first update of federal food policy in five years.

The advisory panel of experts from universities and nutrition organizations across the nation cited mounting research that consumption of cholesterol-rich foods has little bearing on overall levels of cholesterol in the bloodstream. In doing so, it echoes 2013 advice from the American Heart Assn. and the American College of Cardiology that physicians stop steering patients away from cholesterol-rich eggs and shellfish.

Cholesterol from the diet represents only about 20% of the cholesterol circulating in the human bloodstream, so lowering cholesterol intake affects blood cholesterol levels only marginally. While other lifestyle changes — getting regular exercise and maintaining a healthy weight — can help reduce worrisome cholesterol, medication has become a mainstay of treatment. These drugs bind to and remove excess circulating cholesterol or alter the liver’s overproduction of the waxy substance, which may build up and clog arteries and raise the risk of a heart attack or stroke.

In recommending a reversal on cholesterol intake, the advisory panel has “moved gently in the right direction,” said Cleveland Clinic cardiologist Dr. Steven Nissen. Like much dietary advice given to Americans, strict limits on dietary cholesterol “were never supported by science,” he said.

Foreshadowing a debate likely to take place over the coming months, Nissen said the experts drafting the 2015 Dietary Guidelines should consider going further, reversing the guidelines’ long-standing designation of saturated fat as a “nutrient of concern for overconsumption.” Saturated fats increase blood cholesterol, and the same 2013 report from the American Heart Assn. and the American College of Cardiology that said limits on dietary cholesterol were unnecessary also made the case that there was no reason to curtail consumption of saturated fat.

However, the report released Thursday endorses a continuation of the 2010 Dietary Guidelines’ recommendation that saturated fat make up no more than 10% of daily caloric intake, compared with the estimated 11.1% median American daily consumption of saturated fat now.

Nissen added that the dietary guidelines’ long-standing efforts to greatly reduce sodium intake by all Americans should also come under review. For some people, particularly those with failing hearts, a very low-sodium diet may be dangerous, he said.

The panel’s belated about-face on cholesterol, Nissen said, typifies a pattern of American medical and nutrition advice: Too often, physicians have dispensed recommendations that have little to no basis in research. And when solid research suggests their advice has been wrong, they are reluctant to budge.

Physicians and nutritionists vilified fats of all kinds in the 1980s and 1990s, Nissen said. And when Americans reduced their fat consumption, many replaced it with foods rich in carbohydrates and added sugars, which contributed enormously to America’s epidemic rates of obesity and Type 2 diabetes.

“It’s very hard for the people who were the source of all of this conventional wisdom to say, ‘Oh my God, we were wrong,’” Nissen said. “Hubris is a tough thing.”

Others counter that the march of science is slow, and that reluctance to change a long-standing dietary recommendation comes from a fear of confusing Americans or pushing them toward even worse dietary habits.

“You can’t just tell Americans to eat less saturated fat,” said Tom Brenna, a professor of nutrition and chemistry at Cornell University. “We not only have to tell them what to reduce, but we have to tell them what to substitute it with that won’t worsen their health. You don’t want to substitute one poison for another.”

Twitter: @LATMelissaHealy