Type 2 diabetes, once considered a disease for adults, is increasingly common in tweens and teens

For years, health experts have bemoaned the rise of childhood obesity in the United States. About 17% of kids and teens in the U.S. are now considered obese, a figure that has more than tripled since the 1970s, according to data from the

A report in this week’s edition of the New England Journal of Medicine lays out one of the consequences of all this excess weight: a corresponding increase in childhood cases of

Type 2 diabetes occurs when extra body fat makes it hard for cells to use insulin, a hormone that turns sugar into energy. Over time, blood sugar levels rise and cause blood vessels to become stiff, increasing the risk of life-threatening conditions like heart attacks, strokes and kidney failure, among others. More than 75,000 Americans die of diabetes each year, the CDC says.

Type 2 diabetes used to be called adult-onset diabetes, because it would take years to develop. (That’s in contrast to type 1 diabetes, formerly known as juvenile diabetes, which occurs when the immune system destroys the cells that make insulin.) But these days, doctors are diagnosing type 2 in school-age kids, and occasionally even in toddlers.

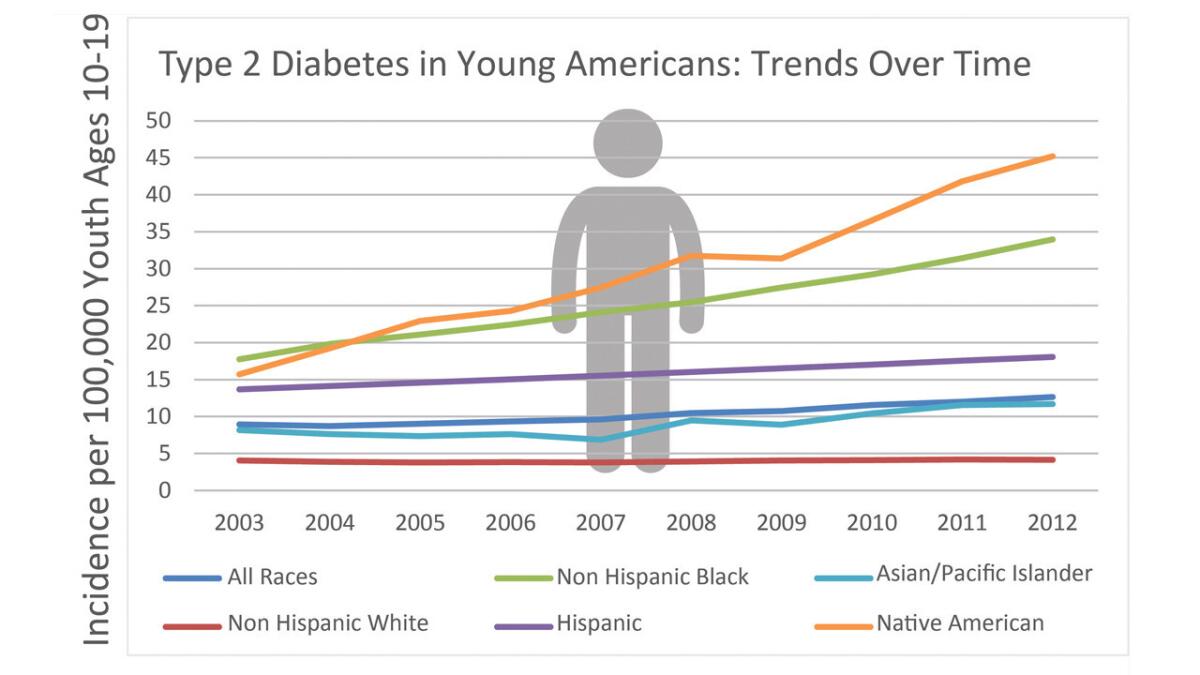

After reviewing data on 10- to 19-year-olds in primarily five states (California, Colorado, Ohio, South Carolina and Washington), researchers determined that 12.5 out of every 100,000 of them had a bona fide case of type 2 diabetes in 2011 and 2012. That compares with nine cases per 100,000 youth in 2002 and 2003.

After accounting for age, gender, race and ethnicity, the study authors found that the incidence of type 2 diabetes in this age group rose by an average of 4.8% per year during the study period.

The increase is detailed in this chart, which comes from the CDC. Here are five take-aways from the new data.

Type 2 diabetes is increasing for youth

Although the difference between nine cases and 12.5 cases per 100,000 people might not sound like much, it means that about 1,500 more kids and teens were being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes each year at the end of the study period compared with the beginning.

The incidence of type 2 diabetes rose pretty much across the board for 10- to 19-year-olds, regardless of age, gender, race or ethnicity. The two exceptions were white kids and youth in Ohio.

Health disparities are increasing

The burden of all these extra cases of type 2 diabetes is not being shared equally.

The racial and ethnic gap was evident in 2003, when the incidences ranged from 4.4 cases per 100,000 people for white youth to 22.6 cases per 100,000 people for Native Americans. By 2012, whites still had the lowest incidence and Native Americans still had the highest, but the gap had increased from 3.9 to 46.5 cases per 100,000 people.

In between were Asian American youth (with 12.2 cases per 100,000), Latinos (18.2 cases per 100,000) and African Americans (32.6 cases per 100,000).

Not only did white kids and teens start out with the lowest incidence of type 2 diabetes, they were the only demographic that didn’t experience an increase in incidence over the 10 years of the study.

The gender gap is widening

At the beginning of the study period, the incidence of type 2 diabetes was seven cases per 100,000 boys and 11.1 cases per 100,000 girls. By the end, the incidence increased modestly for boys (to nine cases per 100,000) but more markedly for girls (to 16.2 cases per 100,000).

After the researchers accounted for demographic factors, they calculated that the annual increase in type 2 diabetes incidence was 3.7% for boys and 6.2% for girls.

It doesn’t matter if you’re a tween or a teen

When the researchers divided the data according to age, they found very little difference between 10- to 14-year-olds and 15- to 19-year-olds.

In 2003, the older teens had a slight edge, with an incidence of 10 cases per 100,000 people compared with eight cases per 100,000 for their younger counterparts. By 2012, that edge had narrowed to 12.9 cases per 100,000 to 12.1 cases per 100,000.

The adjusted annual increase was essentially the same for both age groups — 5.2% for the older kids and 5.1% for the younger ones.

Over time, the effects could be huge

The earlier the disease starts, the more potential it has to do damage.

Globally, the number of years people lived with diabetes-related disabilities rose by nearly 33% between 2005 and 2015, according to a report published last year in Lancet. In addition, the number of years of life lost to type 2 diabetes rose more than 25% in the same period.

That means that even though doctors are doing a better job of treating diabetes and its related conditions, “the overall adverse effect of diabetes on public health is actually increasing,” according to an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine that accompanies the new report.

Follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and "like" Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

What would make a computer biased? Learning a language spoken by humans

Saturn's moon Enceladus might have the right elements to sustain Earth-like life

Your fitness tracker can count your steps, but it's not that good at monitoring your heart rate