Rising temperatures due to climate change are latest threat to bumblebees

Bumblebees already have to contend with lethal infections, deadly pesticides and habitat loss due to agriculture and urban development. A new study shows they have another cause for worry: climate change.

Over the last century, warming temperatures have noticeably shrunk the areas where bumblebees live in North America and Europe, researchers report in Friday’s edition of the journal Science.

The overall effect of climate change is to “crush bumblebee species in a kind of climate vise,” said Jeremy Kerr, an ecologist at the University of Ottawa and lead author of the study.

Kerr and his colleagues examined more than 420,000 bumblebee museum specimens collected from 1901 to 2010. The specimens represented 67 species of bees that lived in North America and Europe. Using records of the year and location where each bee was gathered, the researchers mapped out the historic ranges of the pollinator populations.

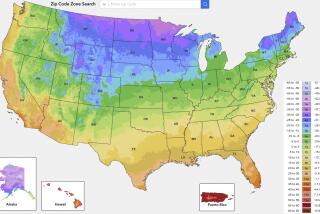

To see how the ranges changed over time, they created maps for a baseline period of 1901 to 1974 and for three recent periods with higher global temperatures: 1975 to 1986, 1987 to 1998 and 1999 to 2010. They also examined the extreme high and low temperatures that bees faced in each of the periods.

Across both Europe and North America, the southern ranges for bumblebees moved northward by an average of 185 miles between 1901 and 2010, the researchers reported.

Temperatures in these vacated zones all rose, though by different amounts in different areas over that time period, Kerr said. But it’s not just general warming that’s a problem - bumblebees are especially vulnerable to extreme heat events, which have become more frequent as a result of climate change.

“Bumblebee populations have disappeared during heat waves in places like southern Europe,” Kerr said. “Even though the average temperatures might not be terribly high, these transient but intense heat waves can sometimes push bumblebee species past conditions they can tolerate.”

As the southern end of their habitat became inhospitable, the habitable zone on the northern end should have expanded. For instance, the coldest temperatures bumblebees experienced between 1999 and 2010 were 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit (2.5 degrees Celsius) warmer than between 1901 and 1974.

However, the bees did not adapt by moving farther north, as butterflies and some other species have done, Kerr said.

Researchers investigated other possible explanations for the bumblebees’ shrinking range, like increased use of neonicotinoid pesticides and land-use change. Though both are grave threats to bee species, they aren’t responsible for the range losses seen in the study, researchers said. The intensity of land use is different in Canada than in northern Europe, but the invisible northern barrier was seen in both places, the researchers wrote. Also, bumblebee ranges started to contract before neonicotinoid pesticides were widely used, they noted.

The study authors said they weren’t sure why bumblebees had not settled in areas further north. It could be that they aren’t able to effectively set up new colonies, that they lack the appropriate plants to feed on, or that the timing of the plants flowering and the seasons changing doesn’t line up with when the bumblebees need to eat and reproduce, said Leif Richardson, an ecologist at the University of Vermont and one of the coauthors of the study.

Bumblebees are important pollinators of wild plants as well as of food crops. Other research has shown that the common Eastern bumblebee, for example, provides pollination services worth an average of $390 per acre of crops in areas where it is found.

As a result, bumblebee decline could have serious implications for both ecosystem function and food production, scientists said.

“It’s very alarming,” Richardson said. If humans continue to warm the climate, “it doesn’t look very good for bumblebees.”

For more science news, follow me on Twitter @sasha_hl and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.