Using particle physics, scientists find hidden structure inside Egypt’s Great Pyramid

Scientists have found a hidden chamber in Egypt’s Great Pyramid of Giza, the first such discovery in the structure since the 19th century and one likely to spark a new surge of interest in the pharaohs. (Nov. 2, 2017)

An international team of scientists has discovered a large hidden cavity within Egypt’s Great Pyramid of Giza, and they did it by looking for muons — particles sent to Earth by cosmic rays from space.

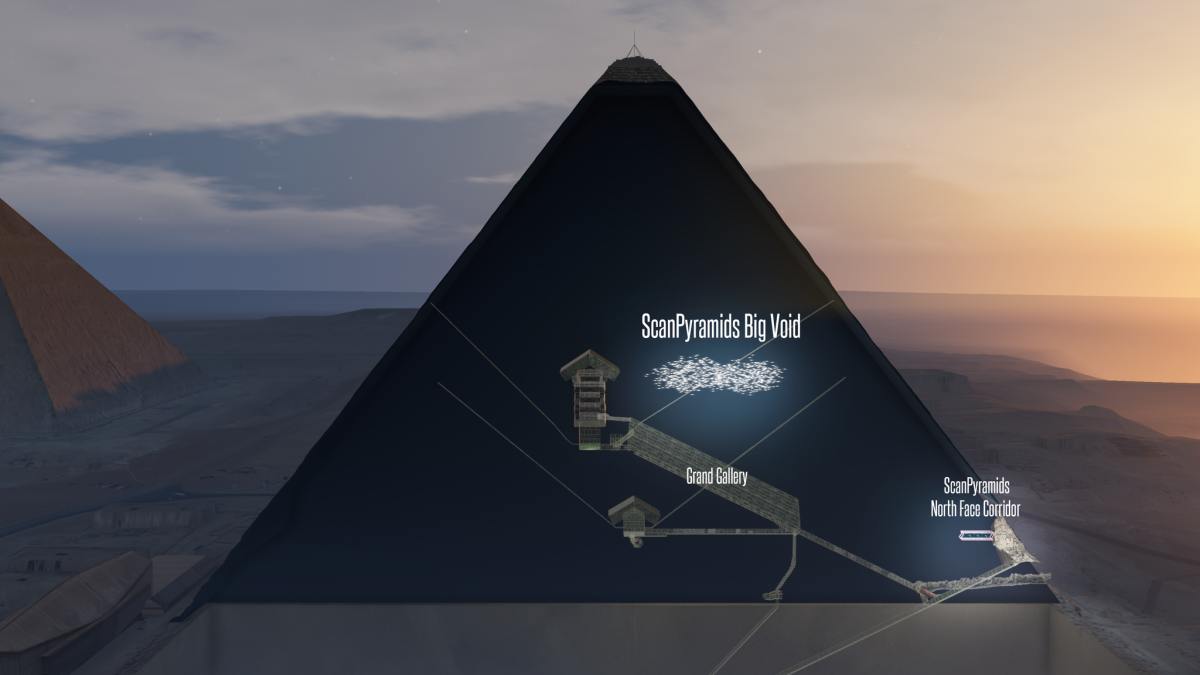

The mysterious cavity, described Thursday in the journal Nature, is at least 30 meters long. And though the researchers aren’t sure whether it’s straight or inclined, whether it’s one large space or a series of smaller ones, the discovery has already triggered interest among archaeologists as to the purpose of the void.

“What we are sure about is that this big void is there,” said Mehdi Tayoubi, president of the nonprofit Heritage Innovation Preservation Institute in Paris, which led the effort. ”But we need to understand [it] better.”

The Great Pyramid of Giza was built during the rule of the Pharaoh Khufu, also known as Cheops, whose reign lasted from 2509 to 2483 BC. The largest of the pyramids, it stands some 139 meters high and 230 meters wide. Tourists enter the pyramid from a tunnel that was dug at the behest of Caliph al-Ma’mun around AD 820.

Three known chambers sit within this enormous structure at different heights: an underground chamber, the Queen’s chamber, and finally the King’s chamber. All three are connected by corridors, the largest of which is the Grand Gallery, which measures 8.6 meters high, 46.7 meters long and up to 2.1 meters wide. The King’s and Queen’s chambers each have two “air shafts” that were mapped by robots between 1990 and 2010.

But much of the pyramid’s interior structure has remained a mystery, in part because there are very few documents from Khufu’s time describing the building’s design and construction.

Other research teams have searched for hidden “chambers” by measuring tiny variations in the pyramid’s gravity or by using ground-penetrating radar. The results of those efforts have been inconclusive.

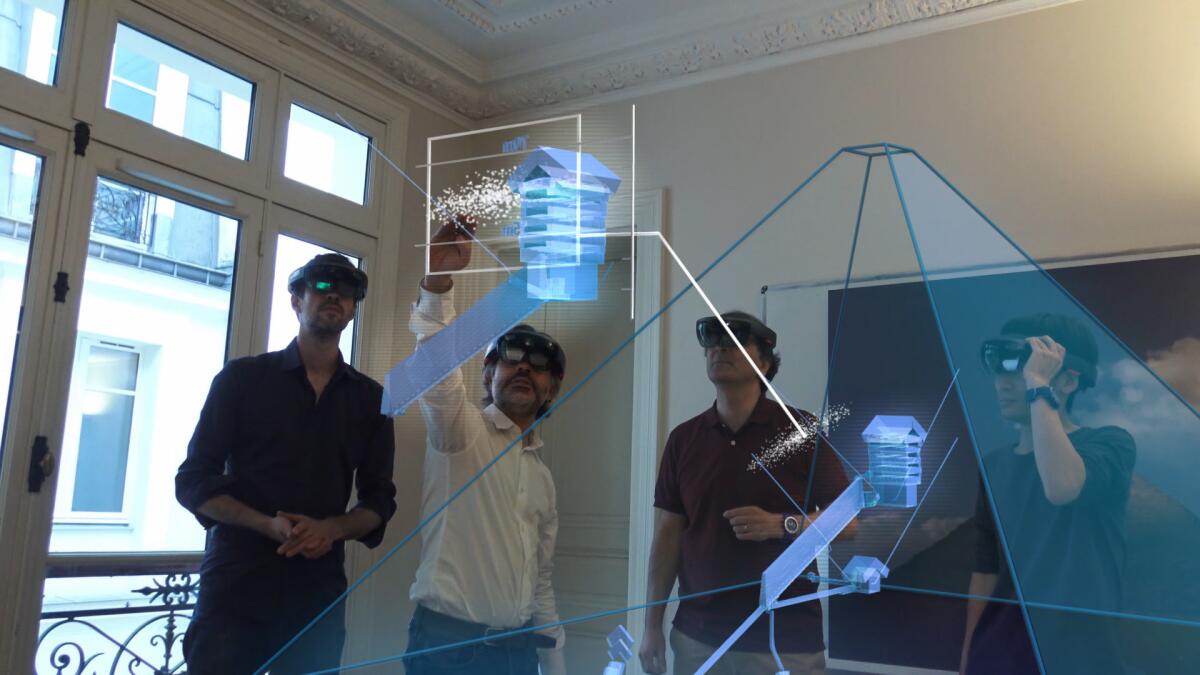

For this project, a team of researchers attempted to boost their odds of success by adding muons to their scientific toolkit.

Muons are subatomic particles that are produced when cosmic rays — high-speed atom fragments that hurtle through space — smash into the atmosphere. They carpet-bomb Earth at a rate of 10,000 per square meter per minute.

These tiny particles can pass through hundreds of meters of rock before decaying or being absorbed. This turns out to be very handy for scientists who want to probe a pyramid somewhat in the way that doctors use X-rays to examine a bone inside your body.

This technique had been pioneered decades ago by Nobel laureate Luis Alvarez of UC Berkeley, who used muon tomography to probe the smaller Khafre pyramid nearby. He concluded that there were no large hidden voids within the structure.

Scientists with the ScanPyramids project who are studying the Great Pyramid had already found hints of what appeared to be a corridor behind the chevrons on the structure’s north face.

In their latest work, they placed detectors in the Queen’s chamber and discovered an enormous space that stretches at least 30 meters long and lies about 21 meters above ground level. The muon levels in that space show that it must hold roughly as much volume as the Grand Gallery, which lies below it.

The muon signal was so strong that the scientists could detect it from outside the pyramid entirely.

The discovery is a vindication of Alvarez’s technique, said Jerry Anderson, a retired physicist who worked with Alvarez back in the 1960s.

“I am very excited and very pleased,” Anderson said.

Alvarez had looked at Khafre’s pyramid instead of Khufu’s because so little was known about the smaller pyramid, Anderson said.

“I wish we had worked in the Great Pyramid, now that I look back on it,” he said with a laugh.

Peter Der Manuelian, an Egyptologist and director of the Giza Project at

“I think it’s a big discovery and an important one,” said Manuelian, who was not involved in the research.

But he was quick to note that it was too early to say what this space was for — or whether it was intentionally made at all.

“The Great Pyramid is a magnet for speculation, both reasonable and unreasonable,” Manuelian said. “So whenever anything new pops up, the imagination tends to fly.”

The study authors said they avoided calling the space a “chamber” because they do not yet know its purpose. They invited Egyptologists to begin to probe the nature of this strange space.

“There are still many architectural hypotheses to consider,” they wrote in Nature.

Christopher Morris, a nuclear physicist at Los Alamos National Laboratory who was not involved in the work, pointed out that there are limits to what muons can reveal. He said he hoped the researchers would soon be able to get a bot’s eye view of the space.

Follow @aminawrite on Twitter for more science news and "like" Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

Alcohol reshapes the brain in ways that make rats more likely to become cocaine addicts

At Mt. Wilson, scientists celebrate 100th birthday of the telescope that revealed the universe

How your brain processes certain words can help predict your risk of suicide

UPDATES:

This story has been updated throughout.

This story was originally published at 5:20 a.m.