Parades, parties and port-a-potties: Eclipse mania is taking hold from coast to coast

The Great American Eclipse

It looks like an ordinary Nebraska cornfield, but Louis Dorland sees something more: an ideal place to observe the Great American Eclipse.

The horizon extends for miles to the west and the east, with few obstructions to mar the view. It’s just a two-hour drive from his home in the Omaha suburbs, but because it’s deep in the country, he figures the area won’t be packed with skywatchers on the big day.

Dorland spent an entire day scouting locations in search of a quiet spot to spend about 2 1/2 unforgettable minutes, when day will eerily give way to night. The tricky part was making sure the guy who owned the cornfield wouldn’t mind Dorland’s setting up his binoculars and picnic blanket on the side of his property.

With some trepidation, the retired IT worker hopped out of his minivan and approached the farmer steering a green tractor near the side of the road.

“I was worried he might not be pleasant about it, but he was absolutely fine,” said Dorland, who expressed his thanks by offering the farmer several pairs of paper eclipse glasses to share with his family.

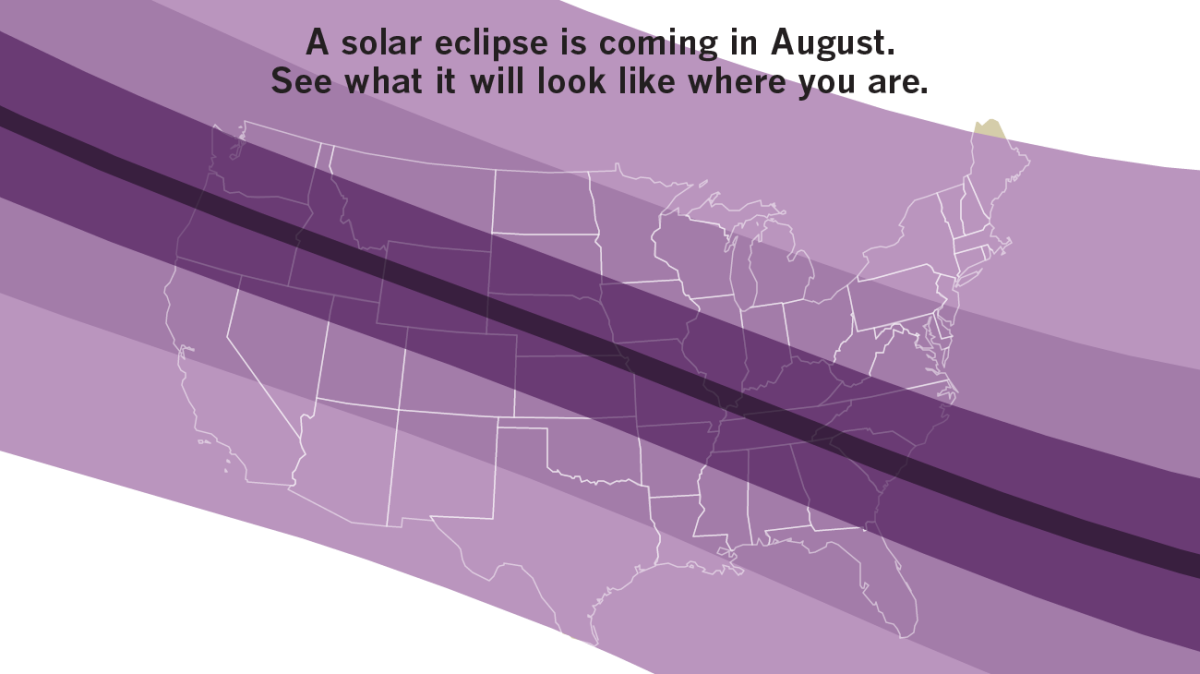

Thanks to an unusual celestial alignment, the moon’s shadow will race across the United States on Aug. 21, tracing a 2,800-mile arc from Oregon to South Carolina. It will take about 90 minutes for the eclipse to travel from coast to coast, plunging a roughly 70-mile-wide swath of land into a twilight-like darkness in the process.

Only in this so-called path of totality will the world grow dark enough to see the stars as the moon blots out the sun. The temperature will drop, crickets will begin to chirp and farm animals will lie down and go to sleep. If skies are clear, observers will be able to see the sun’s halo-like corona, which is usually obscured by the brightness of the photosphere.

An estimated 12 million Americans are fortunate enough to live in the path of totality. But for the rest of us, viewing the first total solar eclipse to stretch across the continental U.S. since 1918 will take some strategizing.

Finding the right spot

Serious eclipse chasers often stake out their viewing spots years in advance of a total eclipse.

Victor Roth, a retired state park employee from Santa Cruz, thought he was way ahead of the curve when he discovered the Kah-Nee-Ta Resort & Spa last summer.

Scientists are ready for the Great American Eclipse »

The resort is in Warm Springs, Ore., about 100 miles southeast of Portland and well inside the path of totality. Roth was eager to share this information with the hotel’s reservation manager.

“I told her she had a real marketing opportunity here,” he said. “I thought I was really helping her out.”

But when Roth tried to make reservations for himself and his friends, she told him all of the lodge’s 137 rooms had been booked three years earlier.

As awareness of the eclipse continues to grow, towns and cities along the path of totality are bracing for an onslaught of visitors.

“Whatever the biggest event in town is, they are going to get at least twice as many people — and usually more than that,” said Kate Russo, an eclipse chaser and consultant who is helping communities prepare for the crowds. “This is not just a science event. This is a human event and something very powerful and life-changing.”

This is not just a science event. This is a human event and something very powerful and life-changing.

— Kate Russo, an eclipse chaser and consultant who is helping communities prepare for huge crowds on Aug. 21

Andy Sinwald, supervisor of special events for the city of Isle of Palms in South Carolina, said he didn’t realize just how big a draw the eclipse would be until he attended a two-day workshop sponsored by the American Astronomical Society in March. Now, the small barrier island with a permanent population of 5,000 is preparing for an influx of up to 50,000 people who will watch the eclipse on the beach.

“We’re marketing it as your last chance to see the eclipse before it leaves America,” Sinwald said.

A 10-year wait is almost over

Gordon Emslie, an astronomy professor at

“I’m a solar physicist,” he said. “I follow these things.”

Emslie has experienced totality in Turkey, France, Hawaii and Scotland. But even a decade ago — before Barack Obama became president or the first iPhone was released — he knew the Great American Eclipse would be special. Plus, it would pass right over his stately campus.

Emslie didn’t want to seem crazy, so he waited six years to alert the school’s presidential council about the celestial event coming its way.

“The reaction was, ‘OK, can you get back to us in 3 1/2 years?’ ” he said.

Now, the university is preparing to welcome 15,000 schoolchildren who will watch the eclipse from the football stadium. Tens of thousands of other spectators are expected to flood the campus as well.

Emslie and his 35-member Eclipse Committee have made sure the local utility will cut power to the street lights so they won’t automatically turn on when darkness falls.

“We’ve discussed this with the city, county and state,” he said. “We have not alerted the National Guard, but the authorities are aware that this could get interesting.”

Calling in the National Guard

The town of Hopkinsville, Ky., about 60 miles to the east, has not shown the same restraint.

“We put in a request with Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin to have 85 National Guard military police, simply to assist with the immense amount of traffic that we anticipate,” said Brooke Jung, who has served as Hopkinsville’s full-time eclipse coordinator since September.

The town of about 30,000 is near the Point of Greatest Eclipse, which means it’s where the moon will look biggest relative to the size of the sun. Not coincidentally, it’s also near the place where the eclipse will last the longest. That makes it especially appealing to astronomy enthusiasts.

“We probably get 50 calls about the eclipse a day, on average,” Jung said.

We probably get 50 calls about the eclipse a day, on average.

— Brooke Jung, the full-time eclipse coordinator in Hopkinsville, Ky.

Hopkinsville began preparing for hordes of visitors about 10 years ago, when an eclipse chaser called the head of the Convention and Visitors Bureau to alert officials about the town’s designation. Since then, the community has enthusiastically embraced its role as eclipse central, even adopting the name “Eclipseville” and painting a mural on the building next to Whistlestop Donuts, an iconic spot next to the railroad tracks that most everyone sees when pulling into downtown. It is renting 15-by-15-foot viewing stations in local parks for $30, parking pass included.

“We have reservations from people in 34 different states and 12 different countries,” Jung said.

The local Catholic church will host Brother Guy Consolmagno, the chief observer of the Vatican Observatory, for the event. (He will deliver a talk on the intersection of faith and science on the eve of the eclipse.) About half a dozen

Hopkinsville also happens to be the place where most of the world’s bowling balls are manufactured. If you’re wondering whether a solar eclipse bowling ball is being produced, the answer is, of course.

Parades, parties and port-a-potties

Ravenna, Neb., will honor its spot along the path of totality by hosting its first music festival, a parade featuring an active NASA astronaut and a cruise-in night for the town’s 1,300 residents to drive around in old muscle cars before enjoying an ice cream social.

The five hotel rooms on Grand Avenue have been booked for months.

“We had a guy fly in from Japan last year and personally book a room,” said Gina McPherson, director of the Ravenna Chamber of Commerce and the town’s eclipse coordinator.

Two hundred miles east, in the even tinier village of Steinauer, Neb., (population 75), preparations also are underway. The night before the eclipse, residents and tourists will attend a star party in an open field, where a local astronomer will point out planets and constellations in the night sky. With the town’s three street lights turned off, the Milky Way should be easily visible.

I want to feel my hairs stand on end because of the charge in the air. I want to see the aura of the sun.

— Terry Wagner, who is renting plots for eclipse viewing in Steinauer, Neb.

Because there are no restaurants in the village, the Community Club will put on a big country breakfast at the church on Aug. 21, and the Altar Guild will make bagged lunches for people to take to specified viewing areas. The eclipse will start at 1:03 p.m. local time and last for 2 minutes, 37 seconds.

Terry Wagner, the great-granddaughter of one of the town’s founders, is charging people $20 to spread out a blanket on a public field just south of town, to help cover the cost of the extra port-a-potties. It’s going to be a busy day, but Wagner said she can hardly wait.

“I want to feel what it’s like when the temperature drops 20 degrees,” she said. “I want to feel my hairs stand on end because of the charge in the air. I want to see the aura of the sun.”

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and "like" Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

The Great American Eclipse is 100 days away, and scientists are ready

UPDATES:

FOR THE RECORD: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Santa Cruz eclipse enthusiast Victor Roth as Victor Russo.