Coronavirus Today: The $13 N95 mask

Good evening. I’m Sam Schulz, filling in for Diya Chacko, and it’s Thursday, April 23. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus outbreak in California and beyond.

Forget the old timeline. The silent, deadly spread of the coronavirus in California began far earlier than state officials previously thought, and Santa Clara County’s health director now believes it was circulating in the Bay Area as early as January. New revelations this week hold important clues to understanding the first cases, which were silently multiplying within communities at a time when health officials were still focused on the threat posed by cruise passengers and travelers from China.

By gauging how many people have been exposed to the virus — many without even realizing it — researchers at Stanford University and USC hope to work backwards to recreate historical glimpses of coronavirus activity. That will help them understand how fast it spreads and how lethal it is, which in turn will lead to better computer models that public officials will rely on in deciding when to dial back stay-at-home orders and how to handle a potential second wave. And Los Angeles County just got a new appreciation of how lethal the virus is: COVID-19 is now the county’s leading cause of death.

In California, there is still no timetable for reopening, despite the wishes of some cities. Some experts have cautioned against letting some areas reopen before others. “The problem with counties coming up piecemeal is about whether they create magnets,” said Dr. George Rutherford, a UC San Francisco epidemiologist and infectious diseases expert. (A similar confusion appears to be playing out in Texas, where a Fort Worth suburb’s sudden move to reopen has pitted neighbor against neighbor. Said one emergency room doctor: “You have people coming out saying, whose order do we follow?”)

Which is ultimately worse: reopening the economy now so that people get back to work, or keeping it shut and prolonging the financial misery to contain the virus for longer? Reopening now won’t just put lives in jeopardy, according to most mainstream economists. It also threatens to expand and extend the already catastrophic economic damage. Economists who examined the situation came to this conclusion: Cities that intervened earlier and more aggressively benefited by both limiting deaths and showing faster long-term economic growth afterward.

More than 26 million Americans have filed for unemployment benefits in the last five weeks, and on Thursday, the House voted to approve another half-trillion dollars worth of economic relief — most of it to replenish a small-business loan program and to fund hospitals and testing. President Trump is expected to sign it. Next, Congress will turn its attention to what is already a deeply partisan fight over another bill to address the pandemic’s economic effects.

For all the economic pain, there’s one sector that’s cashing in. California taxpayers are paying steep prices for masks amid a global shortage of medical equipment, according to a Times review of hundreds of state contracting records. State officials are paying more than 300% above list prices as they navigate a marketplace rife with fraud and price gouging; in one case, they bought more than 1,400 masks at $12.74 each. Officials defended their actions, saying there is intense competition.

Indeed, the U.S. has been consistently outpaced in the global race for supplies, and that has worsened its shortages, business leaders said. The Trump administration, unlike governments in many other wealthy countries, waited months to develop a centralized, coordinated strategy to secure protective equipment from China, the leading manufacturer. Trump is still directing states to make their own arrangements, in contrast with other countries’ strategy of leveraging their centralized purchasing power.

By the numbers

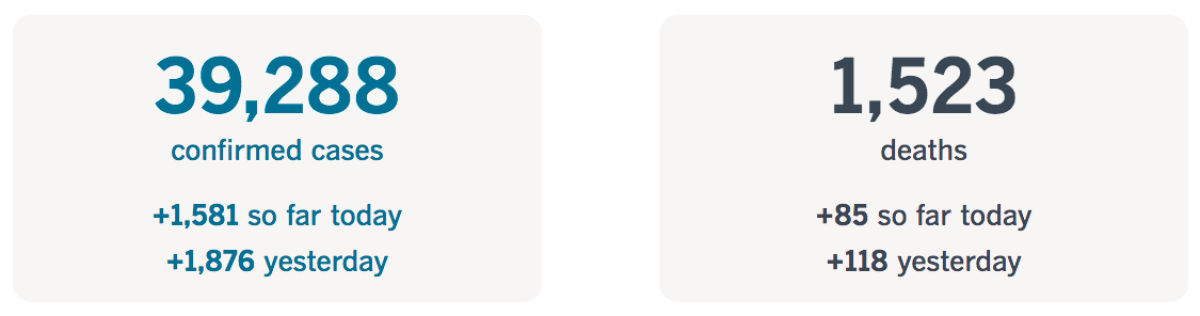

California cases and deaths as of 5:00 p.m. PDT Thursday:

Track the latest numbers and how they break down in California with our graphics.

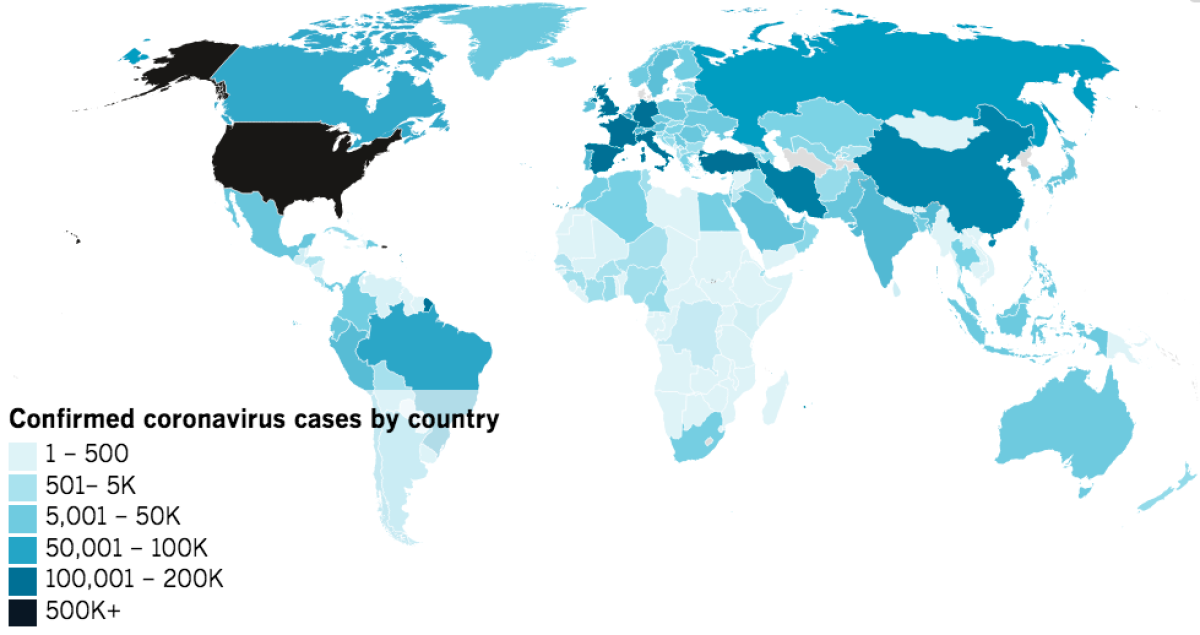

Where is the coronavirus spreading?

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times.

Around California

MOCA on Mondays. The Broad on Tuesdays. The Hammer on Wednesdays. For eight years, Ben Barcelona, 81, was perhaps Los Angeles’ most devoted museum-goer, doggedly pursuing an obsessive routine that kept him fit and offered an emotional lifeline. Now that the coronavirus has curtailed it, he’s filling the void with art books, including one on MOCA’s architect, and artist interviews on YouTube.

The pandemic is freezing the Southern California housing market and upending the lives of landlords and tenants alike. To Alexis Rosen, who doesn’t know how she’ll pay May rent, “the virus is almost secondary” to her panic about housing. Diana Bustamante, who became a landlord just last year, said she didn’t want her tenants to end up homeless. “The reality, however, is that I might be forced to sell the house and that they may end up without a place to live anyway. So how is that a safety net for the renters?”

For those who have lost their homes, counties are leasing hotels to house them. But in some areas, from Pacific Palisades to the South Bay, those deals have run into stiff opposition from locals who don’t want more homeless people in their neighborhoods. Newsom has said statewide efforts, dubbed Project Roomkey, have made real progress getting people off the streets. But one San Bernardino Council member summed up the backlash: “We aren’t the dumping ground.”

A different state relief effort, Newsom’s allocation of $75 million to help undocumented immigrants who don’t qualify for unemployment insurance, faces a legal challenge from two Republicans running for Assembly seats — one in the San Fernando Valley, one in the San Gabriel Valley. The program, announced last week, would provide $500 to each immigrant without legal status and up to $1,000 per household.

Finally, two separate pieces of good news: It’s getting easier to get tested for the coronavirus (here’s a full list of L.A. County testing sites), and more than 1.1 million Californians with student debt are now eligible for three months’ relief. Under a multi-state agreement, 21 of California’s 24 largest student loan servicers have agreed to a 90-day forbearance, meaning borrowers can stop repaying without facing late fees, fines, collection lawsuits or hits to their credit ratings.

How to stay safe

— Wash your hands for at least 20 seconds! Here’s a super-fun how-to video.

— Stop touching your face, and keep your phone clean.

— Watch for symptoms including fever, cough and shortness of breath. If you’re worried you might be infected, call your doctor or urgent care clinic before going.

— Practice social distancing, such as maintaining a six-foot radius of personal space in public.

— Wear a mask if you leave home for essential activities. Here’s how to do it right.

— Here’s how to care for someone with COVID-19, from monitoring their symptoms to preventing the virus’ spread.

How to stay sane

— Was your job affected by the coronavirus? Here’s how to file for unemployment.

— Here are all the ways to stay virtually connected with your friends.

— Visit our free games and puzzles page for daily crosswords, card games, arcade games and more.

— Here are some free resources for restaurant workers and entertainment industry professionals having trouble making ends meet.

— Advice for helping kids navigate pandemic life includes being honest about uncertainties, acknowledging their feelings and sticking to a routine. Here’s guidance from the CDC.

Around the world

China is less worried about its shrinking economy than about unemployment, which set a record in February. Economic measures have so far focused on keeping companies afloat, and direct cash handouts have been minimal; individuals are largely left to the social security system, which covers only a small fraction of workers and excludes most migrants. The unemployment payments and subsidies it has offered fall far short of covering the tens of millions of jobless people.

Vietnam offers a rare bright spot in the pandemic, but its successes may not be very instructive to other countries. The communist-ruled nation is easing its lockdown after an aggressive containment campaign that involved sealing borders, using the military to track down potential coronavirus cases and fining people for spreading what it deemed to be misinformation. Vietnam’s response was shaped by its fraught ties with China and made possible by a Leninist one-party system that, while adept at tackling health crises, has been criticized for silencing dissent and trampling on individual rights.

Among the many things the pandemic has scrambled: the political fortunes of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who still faces trial for corruption. After failing to win enough support to form a government in three elections in the last year, he has now cut a power-sharing deal that would hand him another 18 months as prime minister. His rival, Benny Gantz, will serve as defense minister before succeeding him atop what some call the “Frankenstein government.” Gantz had vowed never to serve under an indicted premier but suggested the pandemic had changed his mind.

Africa could be the next coronavirus hotbed, a worrying new report from the World Health Organization suggests. The continent registered a 43% jump in reported cases in the last week — and its true number is almost certainly higher, experts said, given its very limited testing capacity. The WHO warned the pandemic could kill more than 300,000 people and push 30 million into desperate poverty.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from Dan Korneychuk, who asks: What are the chances that the coronavirus roars back when next flu season begins?

Reporter Amina Khan explored this question in a story on the possibility of a second wave.

The answer, she found, depends on the nature of the virus itself, our own behavior and the degree to which we prepare for another surge.

The coronavirus outbreak began in the U.S. partway through a typical cold and flu season, and if the virus resurges in the fall or winter, it will have more time to spread under more hospitable conditions. How we use the months before the next flu season begins could make all the difference between whether a second wave can be managed or will dwarf the losses we’ve seen so far.

To prepare, health officials must make testing — both to diagnose infections and identify people who have recovered — more robust and widespread. With a better handle on how many people have survived, scientists can more accurately determine transmission patterns and where communities are on the epidemic curve. Stockpiles of ventilators and personal protective equipment must be replenished, and hospitals must develop surge capacity plans.

Preparations will be key, said Dr. Robert Kim-Farley, a medical epidemiologist and infectious disease expert at UCLA, because COVID-19 will probably be around for the entire 2020-21 flu season — and it’s hard to predict how bad a flu season will be. An influx of COVID-19 patients on top of the usual flu patients could swamp hospitals and raise the risk of patient deaths.

That’s why it will be more important than ever to get your flu shot. It may not reduce the spread of the coronavirus, but it will reduce the odds of being inundated by two outbreaks at once.

Got a question? Our reporters covering the coronavirus outbreak want to hear from you. Email us your questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. You can find more answers in our Frequently Asked Questions roundup and our morning briefing.

For the most up-to-date coronavirus coverage from The Times, visit our live updates page, visit our Health section and follow our reporters on Twitter.