Scams: Brain study suggests why older people are more vulnerable

A very kind woman in her 80s I knew was once persuaded to part with a towering sago palm growing in her yard for $300 -- maybe 10 times less than it was worth -- by some men who knocked on her door.

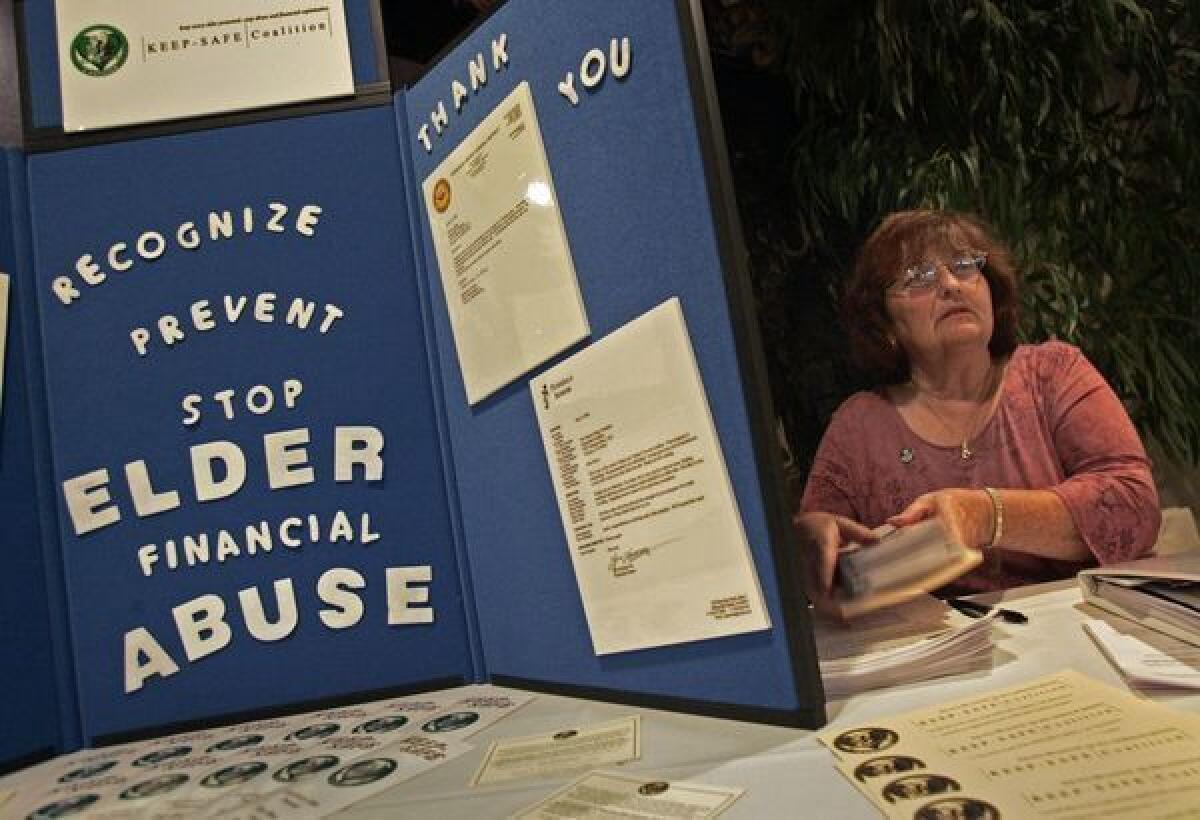

The men were busy digging a trench around the plant when relatives returned and halted the transaction. She had trusted the strangers and was nearly bilked by them -- a perfect example of the kind of thing that happens disproportionately to older people, be it via charity scams, “utility workers” who are actually burglars or bogus travel package deals.

A new paper on brain-scanning touches on why that might be.

The paper, by scientists at UCLA, notes that the FBI and the Federal Trade Commission have already hypothesized that older people may be more vulnerable to scams because they like and trust people more. But why would that be? Wouldn’t a lifetime’s exposure to all the sneakiness and opportunism that strangers (and non-strangers) can toss in one’s direction turn us into hard-bitten cynics by the time we reach a ripe old age?

(It’s been a long time since I gave cash away to people at the airport who “just need enough money for a bus ticket to get home.”)

Elizabeth Castle of UCLA’s Department of Psychology and co-workers examined the responses of 143 older and younger people as they were given two tasks. (There were 40 men and 103 women in the study; those in the older group were age 55-84, and the younger group age 20-42.)

In one experiment, the subjects looked at faces that had been previously rated based on facial features and expressions as either highly trustworthy, neutral or untrustworthy. Though both young and old participants scored equally on the highly trustworthy and neutral faces, the older subjects were more apt to deem the untrustworthy faces both trustworthy and approachable.

In the second experiment, the scientists scanned the brains of participants using functional magnetic resonance imaging, which assesses brain activity by measuring blood flow as well as oxygen levels in the blood.

This time, the scientists found that in younger subjects, a region of the brain called the anterior insula was more active when a subject was assessing the trustworthiness of a face or looking at an untrustworthy face. The effect was muted when older people were performing the same task. The anterior insula is known to be involved in making “gut” decisions and judgments.

The scientists suggest that this heightened tendency to trust is part of what’s known as the positivity bias: People who are older score as happier on a wide array of measures, such as satisfaction with life, recovery from bad feelings after a nasty interpersonal interaction, and even in what they remember -- they’re apt to recall positive things more than they do negative things.

“A visceral early warning system that may alert younger adults to be cautious in the presence of cues regarding trust/mistrust may not be present to the same degree in older adults,” the authors wrote in the paper, which was published online in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

We still do not know why it happens --but perhaps it’s just one of the prices older people pay for an overall higher rate of happiness.