These colorful new maps reveal the hidden diversity of life in Peru’s Andean and Amazonian forests

Not all forests are created equal.

The massive green swaths of Peru’s Andean and Amazonian forests host a more diverse array of life than previously thought — much of which has been hidden beyond the visible spectrum of light until now.

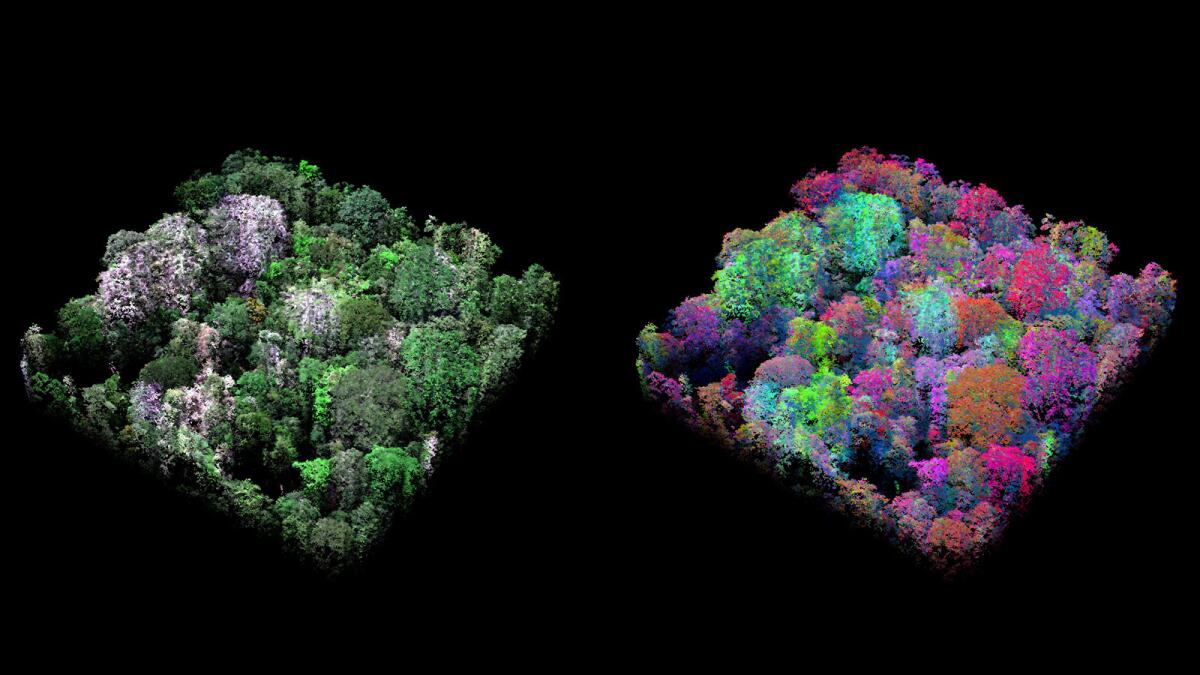

Stanford University scientists have created colorful new maps that show the forest in its full spectral glory. The psychedelic imagery represents each tree species according to its unique chemical signature, creating a kind of tie-dye effect across the landscape that reveals biologically distinct zones in the forest. Before now, these areas may have gone unnoticed — and in many cases, unprotected.

“This changes the name of the game for conservation in the region,” said Greg Asner, an ecologist at the Carnegie Institution for Science at Stanford.

Threats to the region’s forests include oil exploration, ranching and logging, as well as cases of illegal gold mining and a growing demand for palm oil plantations. In one area, deforestation rates have increased by 500% since 2010.

The problem has been that scientists and the Peruvian government didn’t know what they were losing when forestland was converted to a ranch or a mine, Asner said. The flip side is that officials didn’t know exactly what they were protecting when they designated national parks either.

“If you look at any current satellite data … it only deciphers whether there is a forest present or not, not anything about the forest,” Asner said.

The maps, developed with help from the Peruvian government, tell a more complete story of the forest, Asner said. That makes conservation less of a guessing game and more of a tactical one.

“We can’t just do forest conservation based on forest cover, because it’s blind,” he said. “We have to know the kinds of forests that are out there.”

To create the maps, Asner and colleagues first had to “crack the biological code” of the Amazonian and Andean trees — a daunting task, he said. Peru has more than 180 million acres of forest cover, ranging from hot Amazonian lowlands to the higher, cooler Andean treelines.

In 2013, the team took to the skies in a specialized plane to scan the chemical composition of the forest foliage using the Carnegie Airborne Observatory’s battery of laser-guided sensors. Asner and colleagues used the same technique to map the effects of drought on the California forest last year.

The team measured 20 different components found in the trees’ foliage, including nitrogen, water and minerals. Depending on their habitat, plants absorb different nutrients from the surrounding soil, a diet that ends up reflected in their leaves.

From those 20 components, they learned seven were key to identifying the species of a tree, much like spelling out the letters of a name.

“These seven chemicals help us decipher who is out there,” Asner said. “After that, we can pile them into communities of species.”

The chemical signatures revealed that Peru’s forests consist of 36 distinct communities, each with a distinct assemblage of species and its own ecological function. Scientists previously thought there were only three types of forest communities in the region.

The team verified their results by exploring Peru on foot — just like the naturalist Alexander von Humboldt did in 1801 — to confirm the forest types were indeed new to science.

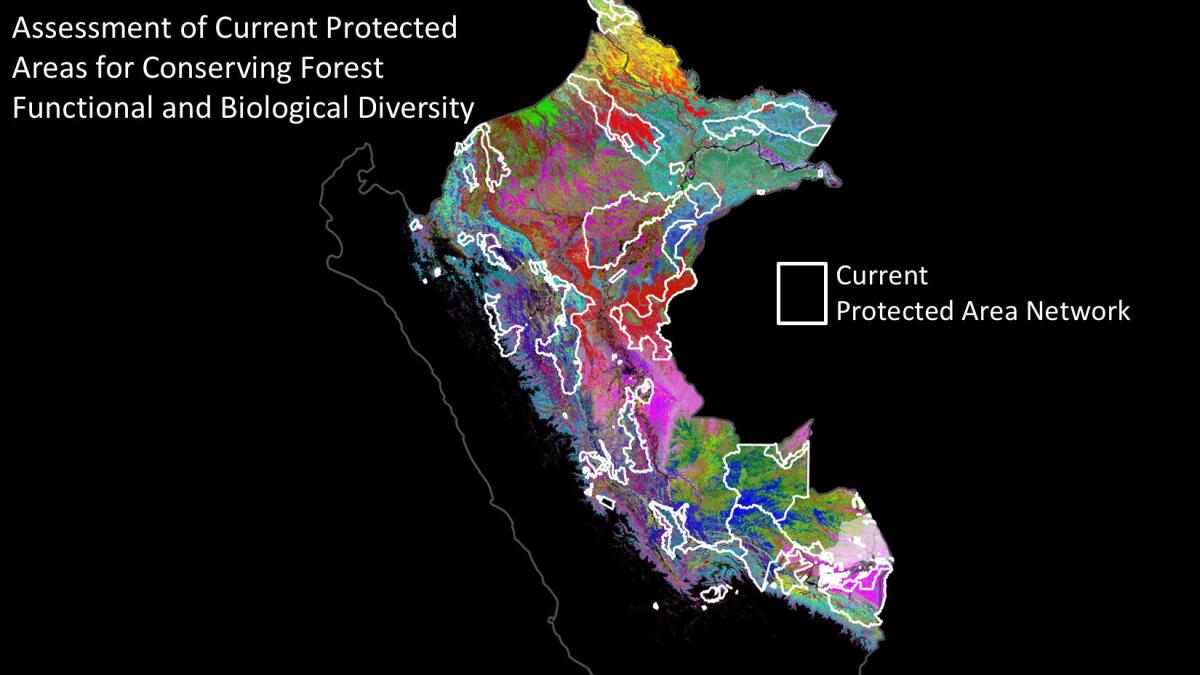

To determine the areas most in need of protection, Asner overlaid the psychedelic imagery with the Peruvian government’s maps of deforestation and protected areas.

The combined data reveal that five communities near the base of the Andes were subject to deforestation rates of up to 17,000 acres per year.

In addition, the study found that 16 million acres of forest are particularly underrepresented in the country’s network of national parks.

The 36 different forest types are shown through the Andes and Amazonian regions of Peru. Current protected areas are outlined in white.

International biodiversity targets emphasize the need to represent all ecosystems in the world’s protected areas, but identifying them has been a challenge. Tropical rainforests such as the Peruvian Amazon are notoriously difficult to study from the ground, and many species there are poorly understood or unknown to science, Valerie Kapos, who heads the United Nations Environment Program’s climate change and biodiversity work, wrote in an article accompanying the Science study.

Applying Asner’s techniques to forests worldwide has “tantalizing” potential to aid efforts to find and protect biodiversity hot spots, Kapos wrote.

Asner and his flying lab have mapped forests in California, Hawaii, Borneo and Ecuador. He admits he can’t cover the whole world by plane — but he can with a satellite.

“We need to go global,” he said.

If he can put his imaging technique into orbit, Asner said, he can make a fresh map of biodiversity on Earth every month. Working with longtime partners at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge, Asner said he is exploring partnerships with public agencies and private organizations to meet the estimated $200-million price tag. The satellite could be ready in two to three years.

“We can find out what we’ve got protected now and what we don’t, and over time we can find out what we’re losing and what’s changing,” Asner said. “I can’t fly the plane everywhere. The only way to do it is to get it in orbit.”

MORE IN SCIENCE

It’s possible to ‘vaccinate’ Americans against fake news, experiment shows

Grocery store tomatoes taste like cardboard — Florida researchers are fixing that

Fossil hunters discover an ancient iguana that lived in a dinosaur nesting site in Montana