Notre Dame may take decades to fix. The first concerns are water and soot

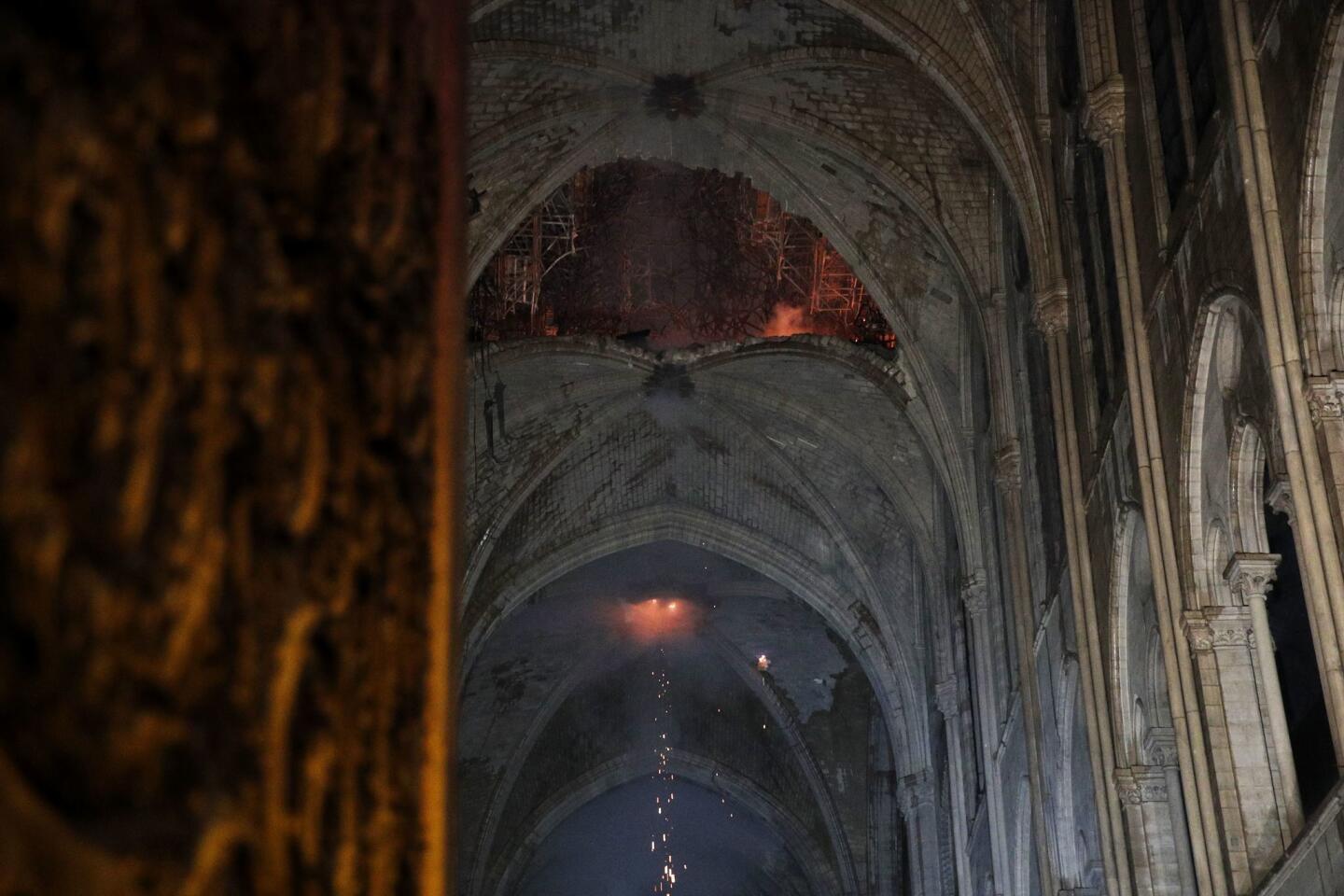

Two holes gape where Notre Dame’s vaulted stone ceiling has collapsed. The cathedral’s 19th century timber spire is gone, as is most of its roof. Portions of the interior walls were blackened by the intense heat of Paris’ most consequential fire in centuries.

As the world absorbs the magnitude of devastation wrought by Notre Dame’s inferno, architects and engineers anticipate a decades-long restoration process replete with unprecedented challenges. Designers will need to navigate complicated structural issues and delicate preservation debates to satisfy an array of stakeholders.

They will all be asking the same question: How do you revive an 850-year-old icon?

“The whole world is watching, and everybody has something to say about it,” said Marc Walton, director of Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts at Northwestern University. “It has to be built for the next 1,000 years. It’s going to be a different structure as a result, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

The first order of business is to dry the cathedral out, said John Fidler, who served as conservation director of English Heritage, a government agency that maintains England’s national monuments.

“There are millions of gallons of water poured into the structure that will seep down to the crypt, the basement,” Fidler said. Pumping out that water could take months, and years may pass before the entire building is completely dry.

“It’s easy to make the surface dry because there are large pores on the surface, but deeper in the stone, the pores grow narrower and it’s more difficult to suck that water out,” he said. “When the walls remain damp, you get mildew and mold and fungus and salt crystallization, which can rupture the pores in stone and cause it to deteriorate on the surface.”

Soot is also a particular concern because it’s so oily, said Rosa Lowinger, a conservator of buildings and sculpture based in Los Angeles.

“People’s first instinct is they want to wash it, but that’s the last thing you should do,” she said. The building’s limestone is porous, so soap and water would drive the soot into its pores. Instead, soot must be removed while dry. “The earliest decisions here — the protocols taken — will define how successful a project like this is.”

While conservators tackle those problems, other teams will get started on the greatest engineering challenge of the entire project: the assessment of the cathedral’s structural condition.

Most analysis methods are tailored toward modern buildings, not stone structures, so engineers may struggle to determine the stability of the damaged cathedral, said Matthew DeJong, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at UC Berkeley who has worked on historic buildings in Europe.

But Notre Dame is surely damaged, said Frank Escher, an architect and preservationist with Escher GuneWardena Architecture in Los Angeles.

“A fire of this nature can weaken a stone structure. It’s too early to say whether it’s safe or not,” said Escher, who is currently restoring the century-old Church of the Epiphany, the oldest Episcopal church in L.A.

As officials begin to stabilize the cathedral and remove damaged materials, the extent of the upcoming rebuild will come into focus. Workers will need to examine the structure stone by stone to evaluate the cathedral’s arched ceiling, or vault. Then they can install the necessary temporary supports.

If the upper portions of the walls prove unstable, the building could require large scaffolding to help bear the weight. Since two-thirds of the cathedral’s timber roof is gone, the vaulted ceilings are exposed to the elements. That means repair teams will need a weather protection plan, DeJong said.

Coming up with the design for Notre Dame’s reconstruction will be a highly collaborative process, involving representatives of the Roman Catholic Church, the French government and the deeply invested public at large. The process will require them to wade into a debate that is roiling the historical architecture community.

“Should you fake history or create something of our time?” said UCLA art historian Meredith Cohen, an expert on the Gothic architecture of Paris. Those discussions could — and should, she said — slow the process.

Notre Dame fire: Charred beams, rescued relics and a vow to rebuild the cathedral »

Cohen herself favors an approach that recognizes the building’s relevance in the 21st century rather than hewing to plans that go back to the 1100s. In practical terms, that would mean not replicating the iconic spire designed by Eugene Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc in the mid-1800s, though it might be replaced with something new.

“A carbon copy is a false history because you can’t re-create the past,” she said. “It would still have a completion date of 2019.”

But Escher said there can be times when it’s appropriate to replicate an original, as when the city of Warsaw was rebuilt after World War II.

“The memory of monuments is extremely important to the people who know a building,” he said. “It’s important, however, that one doesn’t pretend that this is the real historic thing. One has an obligation to be honest.”

For now, the focus is on “stabilizing the building and rescuing anything rescuable,” Lowinger said.

After the years-long design process is complete, workers will begin repairing the vault masonry stone by stone, removing damaged fragments and carving new ones that fit perfectly together. Modern stone-cutter machinery can shape the building blocks, but masons must assemble them manually.

Engineers often use modern materials and methods to repair historic buildings “out of familiarity and expeditiousness,” DeJong said. But he warned that shortcuts could reduce the long-term quality of the building, as seen in cathedrals that have been reinforced with concrete and later devastated by earthquakes.

“It certainly wouldn’t provide long-term durability,” he said. “The solutions are out there; it’s just a matter of taking the long road. The most important thing is that it’s done right.”

How to replace Notre Dame’s wooden roof could be tricky. The enormous supply of timber used for the original roof came from 12th century trees that were hundreds of years old.

“Where do you have a 50-acre forest with 300-year-old trees and people OK with cutting them down?” Escher asked.

One option is to use engineered beams fused from layers of wood, a modern invention that allows for greater strength and longer planks than can be made with natural logs, he said.

Whatever material is used, the roof is sure to be extremely heavy, and structural engineers will need to make careful calculations to determine just how much weight the cathedral’s walls can bear. “Something like that can take years,” Escher said. “One cannot rush something like that.”

Lowinger said she was optimistic that ample resources would be devoted to the project. Already, French tycoons, companies and regular citizens have offered up about $700 million to help pay for repairs.

And there are silver linings. Three medieval rose windows set in soft lead appear to have survived, despite tons of falling debris and scorching heat. The great organ, comprising some 8,000 pipes, has water damage but is expected to make a full recovery.

Lowinger said the reconstruction of Notre Dame could prompt engineers, conservationists and other kinds of specialists to invent new techniques that will be adopted for other projects.

“With a site of this cultural magnitude, there’s the will and there’s the talent,” she said. “The finest solutions will be put together, and we will all learn from it.”

Special correspondent Kim Willsher in Paris contributed to this report.