Many immigrant spouses of California residents left out of Biden citizenship plan

WASHINGTON — Almost as soon as President Biden announced a sweeping executive action in June to set more than 500,000 people on a path to U.S. citizenship, immigrants who won’t qualify under the plan began pushing to be included.

The new policy — unveiled before Biden dropped out of the presidential race as he was attempting to shore up progressive credentials — would shield from deportation undocumented spouses of U.S. citizens if they have lived in the country for the last decade, don’t have any disqualifying criminal convictions and pass a vetting process to ensure they pose no threat to public safety or national security.

The program would allow these spouses, many with children here and deep roots in their communities, to remain in the U.S. and work legally. They would also be allowed to access immigration benefits available to spouses of U.S. citizens. Biden cast the change as a moral imperative to keep families together, as well as an economic benefit to bring more workers out of the shadows.

President Biden’s action will shield those without legal status who are spouses of U.S. citizens and have lived consecutively in the country for at least 10 years.

Formal regulations to implement Biden’s policy could be released any day, with applications expected to open later this month.

But Biden’s proposal leaves out many people who immigration advocates say are equally deserving of protection, but fall short of the proposed criteria. That includes spouses who followed the current rules and voluntarily left the country to apply for reentry, and are now outside the U.S. A Biden administration official said last month that the issue was under review.

Other immigrants would be barred from participating in Biden’s plan due to decades-old border offenses or because they did not pass a U.S. consular vetting process.

Advocates for such families estimate that more than 1 million people married to U.S. citizens are unable to access the pathway to citizenship for various reasons.

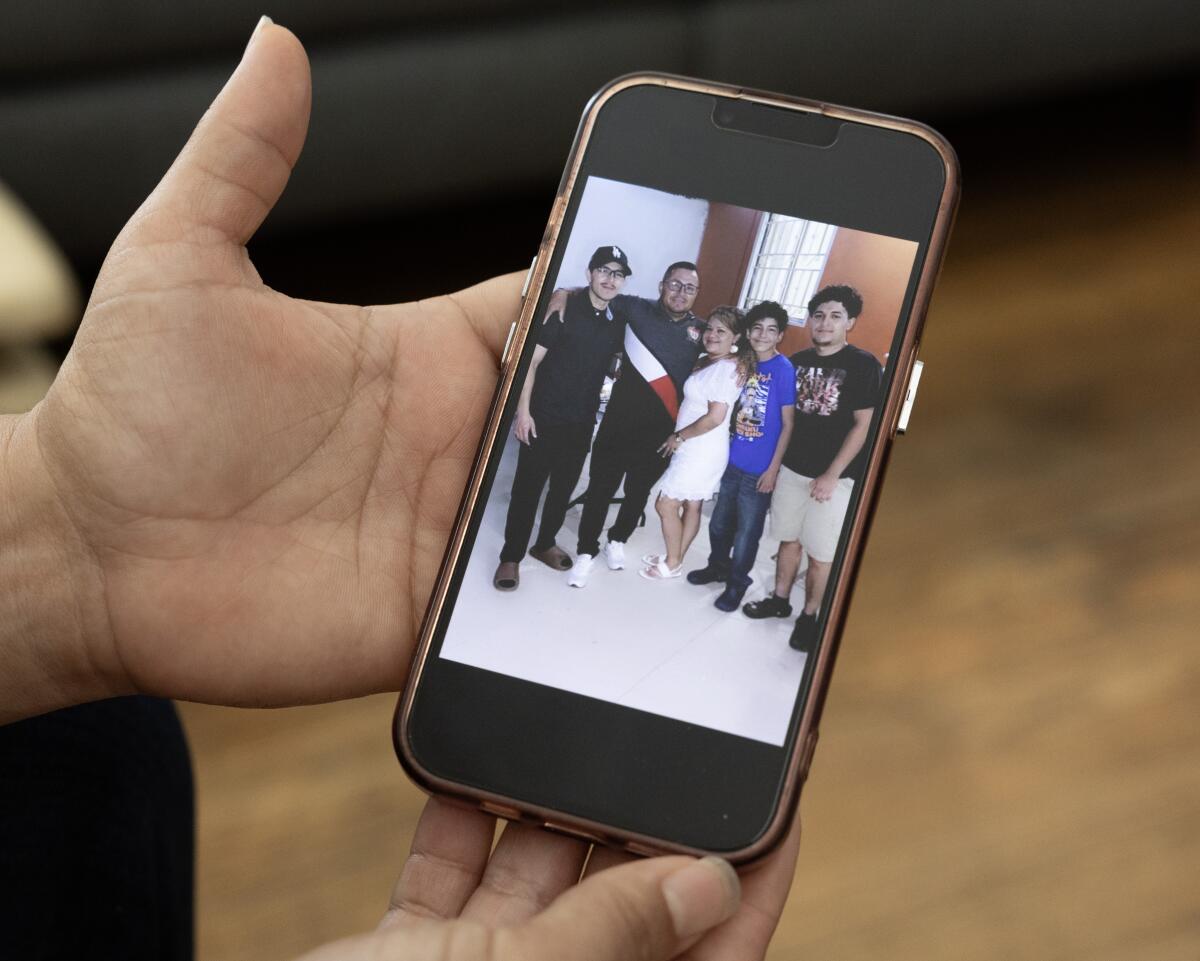

Adriana Gutiérrez, 41, and husband José, 43, are among those who fall through the cracks of Biden’s program, which relies on an authority known as “parole in place.”

José, who asked that his last name not be used, entered the U.S. illegally more than 20 years ago. He met Gutiérrez almost immediately. They married and now live in the Sacramento area with their four children.

They’ve lived a quiet, law-abiding life. But attorneys advised them to not apply for a green card because they may bring unwanted attention to José’s situation.

That’s because shortly before the couple met, José had attempted to cross the border illegally using a cousin’s U.S. birth certificate. He was caught, deported and punished with a lifetime reentry ban. A few days later, he crossed back into the U.S. illegally.

“We’re together, but we’re living in this shadow,” Gutiérrez said. “It seems unfair that we’re having to pay such a harsh price for something that he did over 20 years ago.”

Others won’t receive protection under Biden’s plan because they tried to follow the previous immigration rules.

Immigrants who enter the country lawfully and marry U.S. citizens can obtain legal residency and, later, U.S. citizenship. But as a penalty for skirting immigration law, those who enter illegally and get married must leave the country in order to adjust their immigration status and usually wait at least a decade before being allowed back. In practice, many receive waivers that permit them to speed up the process and be reunited with their families.

Celenia Gutiérrez (no relation to Adriana) said her husband, Isaías Sánchez Gonzalez, left their Los Angeles home and three children in 2016 for a visa interview in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. He assumed he would be quickly readmitted and reunited with his family.

Instead he was barred from returning because, after the interview, a consular officer suspected he belonged to a criminal organization, a claim he denies.

“I dedicated myself to acting right. I never had any problems with the law or police,” Sánchez Gonzalez said. He believes the consular officer may have suspected his tattoos — of the Virgen de Guadalupe, comedy and tragedy theater masks, and the Aztec calendar — were gang-related.

“I like tattoos, but if I had known the problems they would cause, believe me, I wouldn’t have gotten them,” he said.

After the denial, his wife, who was studying to be a nurse, was forced to defer her schooling and get a job to provide for two households while battling depression.

Sánchez Gonzalez, 46, now lives in Tijuana. His wife and children visit one or two weekends a month.

Celenia Gutiérrez, 41, believes her husband could have qualified for Biden’s spousal protections had he simply remained in the U.S. instead of attempting to rectify his legal status.

“We decided to get married so we could get his papers,” she said. “We didn’t want him to get deported. We tried to do everything good, and it still happened.”

Just before Biden announced the program, his administration fought a legal battle against a U.S. citizen from Los Angeles who similarly became separated from her husband after he went to El Salvador for a visa interview and was rejected, despite his assurances of having a clean criminal record.

The government alleged — based on his tattoos, an interview and confidential law enforcement information — that Luis Asencio Cordero was a gang member, which he denied. In June the Supreme Court’s conservative majority ruled against the couple, finding that Asencio Cordero’s wife, Sandra Muñoz, had failed to establish that her constitutional right to marriage extends to living with him in the U.S.

A Los Angeles man was denied a green card over his tattoos. The Supreme Court might take up his case

Attorney Sandra Muñoz and her husband, Luis Acensio Cordero, have sued the federal government after it denied him a visa, in part, over his tattoos.

Due to the uncertainty of reentry, many immigrants have opted to stay in the U.S. and continue risking deportation.

American Families United, established in 2006 to advocate on behalf of U.S. citizens who are married to foreign nationals, is urging the Biden administration to offer a review of more complicated cases, including those of immigrant spouses in the U.S. who know they would face reentry barriers, and those who already left the country for a consular interview and were denied while abroad.

The group believes the vetting process and interviews by consular officials can be too subjective and unaccountable. Such decisions are rarely reviewable by federal courts, though immigrants denied while in the U.S. can appeal.

“We’re asking for discretion,” said Ashley DeAzevedo, president of American Families United. The organization has a membership list of nearly 20,000 people, most of whom are families with complex cases. “It’s very hard to have 10 years’ presence in the United States, be married to a U.S. citizen and not have some form of complication in your immigration history.”

In an interview last month with The Times, Tom Perez, a senior advisor to the president, said the administration has contemplated what to do about immigrants who attempted to legalize their immigration status and ended up separated. It’s unknown how many such families exist, he said.

“How do we deal with folks who actually followed the rules in place and are in Guatemala or wherever they might be?” he said. “That is an issue that is squarely on the table.”

Al Castillo, 55, a Los Angeles man who asked to be identified by his middle name, has been separated from his wife for two years, after she left the country to apply for permanent residency in accordance with the rules.

She hasn’t been denied reentry, but has found the bureaucratic process so complicated and nerve-racking that she’s unsure whether she will be allowed to return or would qualify for protection under Biden’s program. Afraid to take the wrong step, she now finds herself in limbo, her husband said.

The rule, “unless it’s written in the right way, won’t be able to help us,” Castillo said.

When Biden announced the program, he said he wanted to avoid separating families.

“From the current process, undocumented spouses of U.S. citizens must go back to their home country ... to obtain long-term legal status,” the president said. “They have to leave their families in America, with no assurance they’ll be allowed back in.”

Shortly after Biden announced the program, former President Trump’s reelection campaign slammed it. In a statement, the campaign’s national press secretary Karoline Leavitt called it “mass amnesty” and claimed it would lead to a surge in crime, invite more illegal immigration and guarantee more votes for the Democratic Party.

Meanwhile, Vice President Kamala Harris, who is now running against Trump, issued a statement calling the action “a significant step forward” and saying those who will benefit deserve to remain with their families.

On a call with DeAzevedo and other advocates last month, Rep. Lou Correa (D-Santa Ana) said that protecting immigrants who are married to U.S. citizens is an economic issue as much as it is about being on the right side of history.

“You want to keep the American economy strong?” he said. “We need more workers. And what better worker could you bring into the mainstream than those that have been here 10, 20, 30 years working hard, that have children, grandchildren, have mortgages to pay, have followed the law, paid their taxes?”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.