Tired of text spam from political fundraisers? Here’s what to do

“Hi, we chose you for our Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Candidate Assessment but you didn’t respond. It’s only 11 questions,” the text message said, followed by a link.

The scolding came out of the blue, given that I hadn’t received the Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Candidate Assessment, nor had I asked for one. In fact, the sender — the Progressive Turnout Project — was entirely new to me when the message arrived April 15.

I dutifully marked it as spam and blocked the sender’s number. But that wasn’t the end of a stream of unwanted texts from the Progressive Turnout Project and other political groups aligned with the Democratic Party — it was just the beginning.

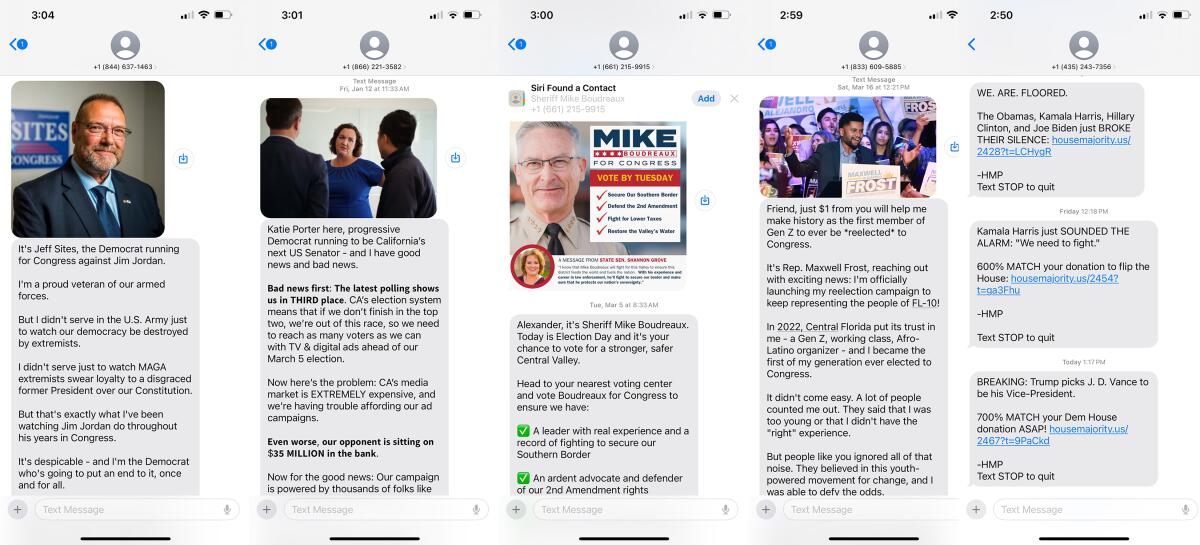

In the three months after that, an increasing volume of unwanted texts landed in my phone, reaching 10 a week by early July, almost all of them asking for me to support a party to which I’ve never belonged or contributed. And every one came from a different phone number, a tactic that evades spam blocks.

The deluge led me to change tactics, and eventually the texts slowed to a trickle, more like the occasional mosquito bite than a nagging headache. But it took persistent action on my part to get to that point.

Here’s a quick explanation of why you, too, might find yourself besieged by political texts and what you can do about them.

How people get on the list for texts

Experts say that political committees and the companies that serve them start with voter registration records, which are available to anyone doing political communications. Those records include the name, address and contact information of every registered voter.

Alternatively, political groups may develop their own models to come up with the names of likely voters, then pay data brokers — a more than $250-million industry — for the matching phone numbers.

Candidates and campaigns aren’t looking to text every voter or likely voter — they’re just going after the ones who are inclined to support them. So they do what other marketers do: They pull together profiles of voters using information available from data brokers, adding information about their race and ethnicity, their hobbies and interests, their likes and dislikes, their magazine subscriptions, and any clues they can find about their politics.

“The same way that a private sector marketer tracks your purchasing habits, a political digital specialist tracks your issue preferences and partisan leanings,” said Dan Schnur, a politics professor at USC, UC Berkeley and Pepperdine. “Every time you post or retweet or like some type of political content, it helps the marketers build a profile to which they can target you based on your strongest interests and leanings.”

Added Chad Peace of IVC Media, a digital communications company based in San Diego, “There are thousands and thousands of layers of data that can be appended to the voter file.”

Once compiled, information about voters moves rapidly among political committees and communications firms — including how voters respond to texts and fundraising appeals. “All this data is shared,” Peace said, noting that when a voter opts out of texts from one organization, another organization can pick up where the first one left off.

What rules govern political texts

Sadly, the federal Do Not Call Registry offers no protection from campaign-related calls or texts. Nor will you find much help from the two federal laws that govern your phone lines, the Telephone Consumer Protection Act and the CAN-SPAM Act. Lawmakers have been reluctant to impose barriers on political communications because of 1st Amendment concerns, not to mention their own need to contact voters.

The law does bar political groups from using an autodialer to spam you with texts unless you give explicit consent in advance. But a 2021 Supreme Court ruling defines an autodialer as a technology that targets numbers it generates on its own, not one that automatically dials a list of numbers programmed into it.

As a result, it is open season for political spammers to target the specific phone numbers gathered by the political parties, campaigns and affiliated interest groups. There are several ways you may have made yourself a text magnet. Did you like a funny Facebook post or online meme? Take an online survey about threats to democracy? Donate to a cause widely backed by liberals or conservatives?

Chief Executive Thomas Peters of RumbleUp, a texting platform used by candidates and causes, said mobile phone companies have consistently said that political texters should get explicit consent before sending messages, but that’s more of a “best practice” than a rule. For their part, campaigns and committees argue that getting consent is difficult or just not possible when you’re trying to reach as many voters as they are, Peters said.

Why do political groups use texts?

Because they work — people are more likely to read an unsolicited text than answer the phone or read an unsolicited email. Campaigns have found that sending text messages is effective for multiple pursuits, including polling, identifying likely voters, winning their support and getting them to the polls, Peters said.

“There is a lot of data online about how receptive different individuals may be to receiving texts,” he said. “Younger people, millennials tend to prefer texts, and baby boomers love texts.”

Fundraisers, meanwhile, are typically paid a percentage of what they generate for a campaign, Peace said. So they have a financial incentive to keep churning out messages.

Texts are also popular for ballot initiatives, which tend to be less partisan and require more voter education, Peters said. He predicted that there will be a lot of texting around the 10 ballot initiatives in California this fall “because of the microtargeting required.”

Ultimately, Schnur said, the goal of the texts is to persuade people to get involved. “First they want your contact information, then they want your interest, ultimately they may want something more tangible, like a contribution or a volunteer commitment or a vote,” he said. “But in this respect they’re no different than every other digital platform on the internet. The more you interact with them, the more time you spend on their platform, the happier they are.”

What can you do about unwanted texts

You’re not completely helpless in the face of the campaign onslaught — federal law requires even political spammers to give you a way to opt out of the messages. If you want campaigns or political groups to leave you alone, reply to their texts with a single word: Stop. You should get a reply right away telling you that you’ve been removed from their list.

The catch, though, is that the opt-out applies only to that phone number and that specific sender. When I replied “Stop” to a fundraising text from the Progressive Turnout Project, for example, I immediately received a text telling me I had been unsubscribed. The very next day, however, I got a text from Progressive Takeover, which is described on its website as “A Progressive Turnout Project Initiative.”

The Progressive Turnout Project declined an interview request, but said in an email, “We follow all required email and text message best practices and protocols, which include having unsubscribe mechanisms in place.”

Over the following weeks, I played whack-a-mole with political texters, replying “Stop” again and again and again. It felt Sisyphean. After a dozen opt-outs I thought I had turned off the spigot, but then the texts began again, this time from Democratic candidates from Arizona and Texas asking for my support (mainly in the form of currency).

I have no better guess about how I got on their texting list than how I got onto the Progressive Turnout Project’s. But Peace said that one of the things the Democratic and Republican parties do for candidates is plug them into the “infrastructure” of data they’ve compiled about voters.

“Once you’re in the system, you’re in the system,” Peace said. There’s really no way out of it entirely, he added; “If you just say, ‘Stop,’ yeah, that number has to stop texting you, but whether it’s that organization or another organization that’s leveraging that same data, [someone] is going to try to reach you.”

If there’s a glimmer of hope, it’s this comment by Peters: “Everyone agrees right now there’s just too much bad texting.” His company built its platform to prevent clients from contacting people who opt out, he said, adding, “It saves [the clients] money, it saves them complaints ... but we are trying to be a good actor in this space.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.