What you need to know about Biden’s plan to end the war in Gaza

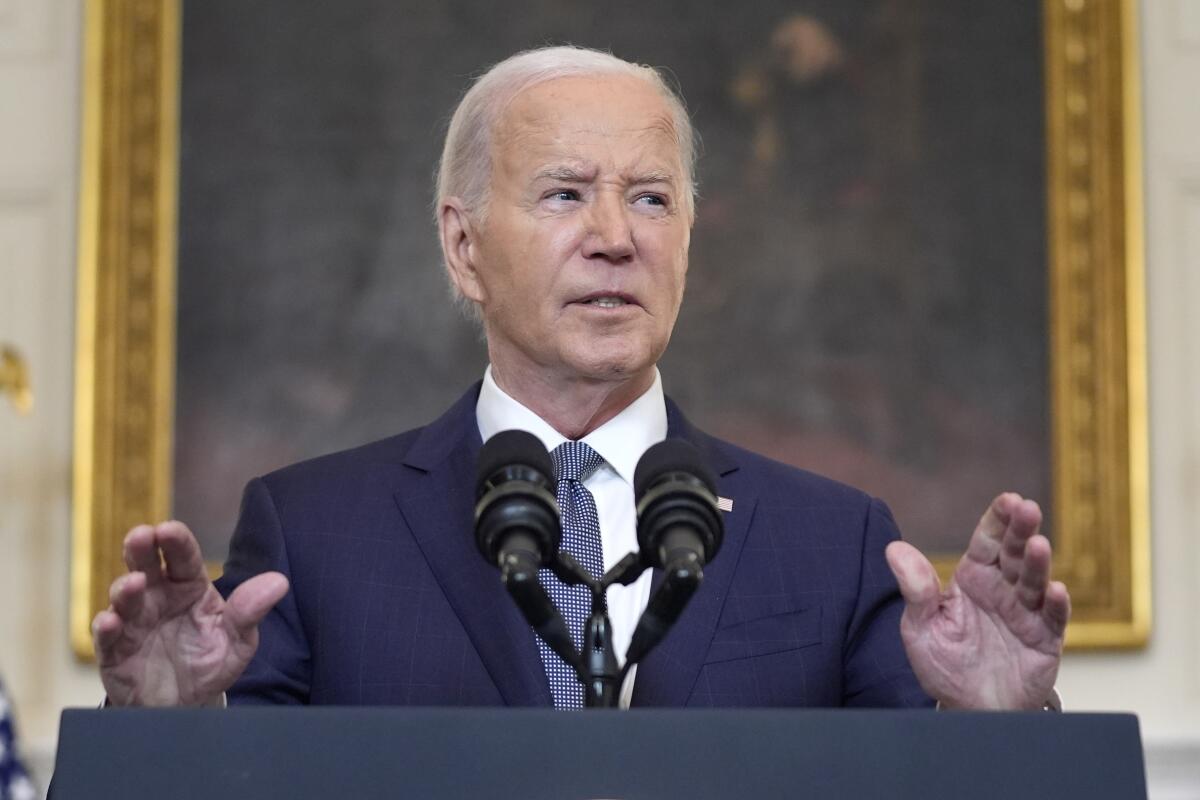

WASHINGTON — When President Biden announced a three-phase plan to end the devastating war in the Gaza Strip, he raised hope that a breakthrough was finally on the horizon between Israel and Hamas militants.

It would include a cease-fire, the release of Israeli hostages and Palestinian prisoners, and a surge in aid for starving Palestinians in Gaza. It was essentially a plan that both Israel and Hamas had previously proposed, U.S. officials said.

Yet days after Biden’s May 31 announcement, neither side is on board. Hamas refuses to go along with the agreement unless Israel commits to a permanent end to hostilities while Israel says several of its demands are not being met.

Here’s a closer look:

What’s the plan?

The Biden administration desperately wants a deal that would stanch the bloodshed in Gaza as well as the hemorrhaging of domestic political support that its backing of Israel has unleashed.

At UCLA, the legacy of the encampment remains an issue of much debate, particularly among Jewish students.

But examination of what the president announced shows the deal to be more of a loose framework — rolled out in three phases — with many details still to be negotiated.

Phase one includes a six-week “full and complete” cease-fire, a withdrawal of Israeli military forces from “populated areas” of Gaza, and the return of Palestinians to homes in northern Gaza they were forced to flee.

Also, Hamas would release some hostages, including women and older people, in exchange for the freedom of hundreds of Palestinians being held in Israeli jails. There would be a drastic ramping up of humanitarian aid delivered to the Gaza Strip.

Then negotiations would begin on a potential phase two, which Biden said he hoped would include “the cessation of hostilities permanently.”

“I’ll be straight with you,” Biden said. “There are a number of details to negotiate to move from phase one to phase two.”

How have Israel and Hamas responded?

Both Israel and Hamas have publicly raised objections over how negotiations would unfold and whether Israel can keep fighting.

Protesters on both sides of the Israel-Hamas war use the word in diametrically opposed ways. What are the origins of the term?

Experts said the U.S. may be keeping these details deliberately ambiguous simply to get Israel and Hamas to engage. It allows both to believe they can get what they want in the negotiations to come.

How has the international community responded?

Rallying allies around the proposal, senior U.S. officials have spent days on the phone to key leaders in the region. Dozens of countries support the deal, U.S. officials say.

The State Department has used its daily briefings to read out declarations of support from countries in Europe, the Mideast and elsewhere, including Morocco, Saudi Arabia, France and Britain.

“When you see the broad support from Europe, from the Arab world, from countries in the Global South, I think it’s a significant statement of ... the opportunity that we have here and how it’s important that we not miss this opportunity,” State Department spokesman Matthew Miller said.

But sustaining support in the middle of a difficult U.S. election year will test the Biden administration’s skills.

A security guard is injured in the attack, which comes amid heightened fears of a wider war between Lebanon and Israel.

“For the three-phase Biden plan to have any chance of becoming a reality, it will require increased U.S. diplomacy in the Middle East at a time when the attention of America and President Biden himself will be elsewhere,” said Brian Katulis, senior fellow for U.S. foreign policy at the Middle East Institute in Washington.

Israel’s incentives and objections

Biden’s decision to publicize the proposal, which he repeatedly referred to as an Israeli proposal, was in part a tactic to force Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to own its terms rather than wiggle out of them.

Before Biden’s announcements, Netanyahu and his wartime Cabinet endorsed the proposal. But afterward, the Israeli prime minister told a closed-door session of right-wing members of his coalition government that there were “gaps” between what Israel had agreed to and what Biden had announced.

U.S. officials saw this as a way for Netanyahu to contain objections from within his coalition, the most extremist members of which are threatening to leave — and topple — the government if Netanyahu accepts the deal.

Netanyahu continues to insist publicly that his war goals have not changed, including eliminating Hamas as a military and governing force after its assaults on southern Israel on Oct. 7. The militant group has sustained heavy losses but has not been destroyed.

In the Oct. 7 attack, militants killed about 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and took 250 others hostage. Israel’s bombardment and ground assaults have devastated Gaza and killed at least 36,000 Palestinians, according to Gaza’s Health Ministry, whose numbers do not distinguish between combatants and civilians.

Biden said the proposal would “create a better ‘day after’ in Gaza without Hamas in power.”

The president also said he believed Hamas, after eight months of war with Israel, is no longer capable of launching a major offensive, an assessment that many in the Israeli military agree with.

Netanyahu is under enormous pressure to bring home hostages; about 100 are believed to still be alive.

Other incentives for Israel, U.S. officials say, is that an end to fighting in Gaza could tap down escalation of a simmering conflict between Israel and Hezbollah, the Iran-backed Lebanese militant group on Israel’s northern border, which has burst into several cross-border attacks in recent days.

Israel is also hoping that peace would lead to improved diplomatic relations with its Middle East neighbors, particularly the region’s powerhouse Saudi Arabia, a carrot that U.S. officials have long dangled.

Hamas’ incentives and objections

U.S. officials said Wednesday they were still awaiting an official response to the proposed deal from Hamas.

Usama Hamdan, a senior Hamas official based in Beirut, said at a news briefing on Tuesday that his group will not agree to the proposal without a clear commitment from Israel to a permanent cease-fire and “comprehensive” withdrawal from Gaza.

“This is what could open the door wide to completing the agreement,” Hamdan said.

The U.S. believes the final say will come directly and only from Yahya Sinwar, the Hamas leader considered the architect of the Oct. 7 attack and who Israel and the U.S. believe is hiding in the vast tunnel network underneath the Gaza Strip.

Word reaches him through a complicated, clandestine system. Documents go from Israel and the U.S. to Qatari negotiators, who transmit them to Hamas political leaders in Doha, Qatar’s capital, who then get word to Sinwar somewhere deep in Gaza.

Some analysts say Sinwar could be persuaded to accept the proposal — even though it does not guarantee the survival of Hamas — because he could in effect proclaim a strategic victory over Israel by claiming credit for the release of hundreds of Palestinian prisoners, an end to Israeli bombardments, and renewed humanitarian aid for the strip. He could portray the military assault he has overseen as having hit the mightier Israel hard and with irreparable deadly force, while destroying its reputation in many parts of the world.

But Sinwar could also use a similar argument — that Hamas is winning— to justify continuing the war, analysts said.

As with Israel, Biden’s decision to go public with the deal was also meant to put pressure on Hamas.

“The goal [with Biden’s announcement] appears to be to spotlight stonewalling by Hamas and right-wing members of the current Israeli government as key roadblocks to a diplomatic settlement,” Katulis said. “It remains to be seen whether the two parties to this conflict will sign up for even the first phase of the proposed deal.”

Wilkinson reported from Washington and Bulos from Beirut.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.