Huntington Beach radiates California cool. The best surfers in the world descend here each summer to compete on waves rolling in under its public pier. Convertibles zoom past towering palms along Pacific Coast Highway. Beachfront homeowners enjoy breathtaking views, and everybody seems to sport a hang-loose attitude.

But trans activist Kanan Durham says Surf City USA and Orange County in general have grown more and more unwelcoming — in some cases hostile — for members of the LGBTQ+ community.

Durham, 32, joined other concerned Orange County residents to form the nonprofit group Pride at the Pier to push back against what they say is a rising tide of hate here that’s emblematic of a trend seen across the country.

When Huntington Beach’s conservative-majority City Council voted last year to ban the display of most flags on city property — including the rainbow flag, a global emblem of LGBTQ+ pride, unity and self-expression — members of the group took to the pier, waving Pride flags in protest.

Their act of defiance was met with a rebuke of sorts when voters approved a measure to write the ban into the City Charter.

Given that only about 26% of registered Orange County voters cast ballots on Super Tuesday in March, Durham worries that many have stopped following local government and therefore may not realize a crisis is unfolding. He’s concerned that some will see battles over Pride flags as little more than business as usual in an era when no aspect of life seems immune from the polarization that defines U.S. politics.

No one should assume that LGBTQ+ Californians are shielded from prejudice simply because they live in a progressive state where Democrats hold sway, he says.

“California is complicated,” says Durham, executive director of Pride at the Pier. “There are a lot of people who see California as this blue bubble where this stuff doesn’t happen. They don’t realize how much danger that marginalized communities face.”

Supporters of the flag ban argue that identity- and issue-based flags are divisive in a city they insist is tolerant and inclusive.

Yet Huntington Beach has had a hard time shaking its reputation as a haven for racists and far-right extremists.

In the 1980s, its pier and downtown were well-known gathering places for skinheads. Two racially motivated killings in the ’90s prompted the creation of a task force to celebrate diversity.

Some saw an improvement in the city’s race relations as people of color became the majority in Orange County, but in 2018, police arrested four members of a Huntington Beach-based white supremacist group on charges of organizing and participating in riots. In 2022, several people in town woke up to antisemitic fliers on their front lawns that blamed Jewish officials in the Biden administration for the COVID-19 pandemic.

If you happen to be LGBTQ+ and live or work in Orange County communities, Durham says, it’s hard not to feel singled out too.

Orange County returned 6 acres of land to the Acjachemen and Tongva people. Tribal leaders say it’s a small step in a movement to protect their heritage.

Durham works in the service industry in Huntington Beach and lives about a 20-minute drive from its famed beaches. He declined to say where in Orange County he resides because he’s concerned about suffering retribution for speaking openly about his identity and controversial policies such as the flag ban.

This fear is widely shared, he says. Some supporters of Pride at the Pier have reached out on social media saying that while they want to attend the group’s demonstrations in Huntington Beach, they worry about being harassed or attacked over their LGBTQ+ identity.

Many want to get involved but don’t know how they as individuals can make a difference in yet another round of culture wars, says Jay Garner, a friend of Durham who has lived in Huntington Beach since 2019.

People need to understand how debilitating it can be to constantly feel as if you must fight for your right to exist and be yourself, says Garner, who identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them pronouns.

“It does weigh on me,” Garner says.

Garner, 32, works as the marketing and communications director for the Orange County chapter of YIMBY Action, a nonprofit that advocates for affordable housing. They describe themselves as butch in appearance — short-cropped hair, button-down Oxfords. Looking different can be risky, even in a beach town that comes across as laid-back, they say.

“I can’t go downtown because I get harassed,” Garner says. “Walking down the street, I will get heckled by somebody who’s just driving by. ... They’ll yell ‘dyke!’ I try not to escalate, because you never know which person is going to turn violent.”

Hate crimes against LGBTQ+ people in Orange County — and across California and the U.S. — have skyrocketed in recent years.

The Human Rights Campaign, a nonprofit advocacy group, has declared a “state of emergency” for LGBTQ+ Americans because hundreds of bills have been introduced in state legislatures that target gender-affirming healthcare, school textbooks that portray queer identity in a positive light, drag shows and the ability of trans Americans to use restrooms, play on sports teams or obtain driver’s licenses that match their gender identity.

In September, the Orange Unified School District unanimously approved a measure requiring schools to notify parents if a student asks to be identified or addressed as a gender that is different from the one they were assigned at birth.

California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta has condemned similar “forced outing” policies approved last year by school boards in Temecula and Murrieta, calling them harmful to the safety and well-being of transgender and gender nonconforming youth. Temecula’s school district also banned all banners except the U.S. and state flags.

When Huntington Beach Councilmember Pat Burns introduced the flag ordinance last year, he portrayed his city as one where “we are all equal.”

“Our flags that we have, that represent our government, are what is important to unify us,” Burns said during a packed hearing on the ordinance.

Not everyone has heeded his unifying message.

Durham recalls his shock when someone at a council hearing in December shouted “pedophile” when he stood to express dismay about the flag ban and other policies. He says he’s also received violent threats on social media.

Garner has attended several hearings with Durham.

“It’s hard to hear this kind of rhetoric from people who I consider to be my neighbors, a part of my community,” Garner says.

Other groups have responded to the hostility in their own ways. Viet Rainbow of Orange County, an organization focused on “equity, healing, joy and social justice” that serves the Asian American community, has organized “Know Your Rights” workshops for LGBTQ+ students and promoted self-defense and personal safety training on its Facebook page.

The spike in antisemitism and other hate crimes in L.A. is grim, but a Jewish neighborhood in L.A. offers glimmers of hope.

Like many who’ve felt compelled to speak out against hate, Durham said he never intended to become a voice for LGBTQ+ rights in Orange County. In the few years since he transitioned, he has mostly kept his life journey to himself, because he knows that not everyone embraces transgender Americans.

“I stayed in the closet long, long after I knew I was trans — for over a decade,” he says. “I didn’t want to lose friends. I didn’t want to lose family. When I came out, I did lose friends. I sent my family a letter, and they just went radio silent.”

Durham came to know Huntington Beach while growing up in the Bay Area. His family visited twice a year to spend time with relatives.

“I saw how wonderful Orange County can be, and I fell in love with it,” he says. “I really think the majority of people who live here are not hateful.”

He points to the fact that in 2021, the city took steps to embrace the LGBTQ+ community, most notably by flying the rainbow flag on city property during Pride Month.

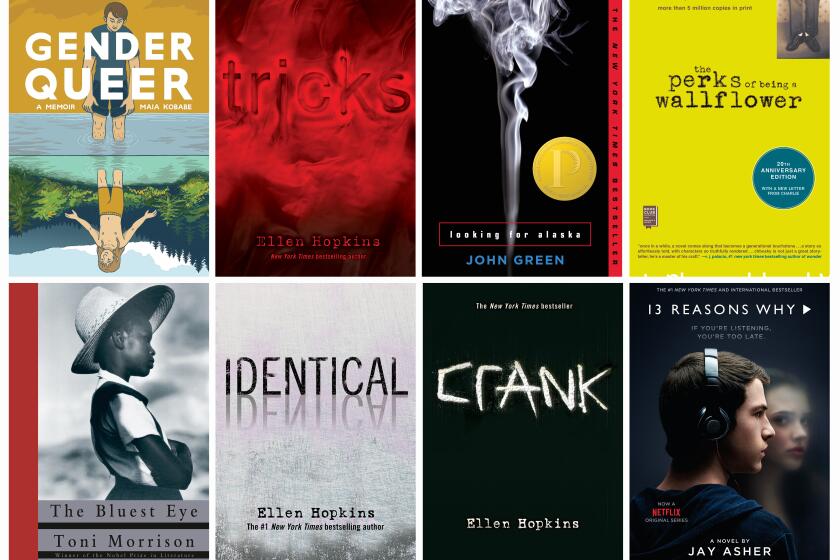

The conservative majority that voters elected to the City Council in 2022 ushered in a dramatic shift — approving, for example, the creation of a parent advisory board to screen children’s books for sexually explicit content and block the purchase of new publications that members deem inappropriate.

Books, literacy and freedom of expression are under assault as never before. A new report shows that book bans at U.S. schools increased 33% since just last year.

Council members who back the library measure have said they are only trying to protect children.

While the harsh words of supporters have attracted the most attention, many residents who’ve spoken out at recent hearings have voiced opposition.

“On one hand, we have more allies in Orange County than ever before, which equates to affirming neighborhoods, businesses, schools and employers,” says Peg Corley, executive director of LGBTQ Center Orange County, a nonprofit advocacy and community service organization in Santa Ana.

“On the other hand, there are pockets of Orange County, like Huntington Beach, where the City Council majority is focused on turning back the clock to the 1950s,” she said.

Corley says the overriding message the council has sent to queer residents, workers and visitors over the last year is, “Go spend your LGBTQ+ dollars somewhere else.”

Angela Mooney D’Arcy of the Sacred Places Institute for Indigenous Peoples says Native Americans and other historically oppressed Californians should share in the fight for reparations.

Durham says Pride at the Pier won’t give up.

Building on the momentum generated by its events last year, the group plans to host its second Pride celebration later this year on the Huntington Beach waterfront. Durham says there are plans to hire extra security to make those who attend feel safe.

Standing outside City Hall, Durham unfurls his own rainbow flag, which is so big it billows around him while he talks about the need to get more people involved in the fight to protect LGBTQ+ rights and freedoms in Orange County.

“We cannot get past this point in our history without joining hands with as many people as possible,” Durham says.

“This is about more than a piece of fabric.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.