Will hackers, trolls and AI deepfakes upset the 2024 election?

In the analog days of the 1970s, long before hackers, trolls and edgelords, an audiocassette company came up with an advertising slogan that posed a trick question: “Is it live or is it Memorex?” The message toyed with reality, suggesting there was no difference in sound quality between a live performance and music recorded on tape.

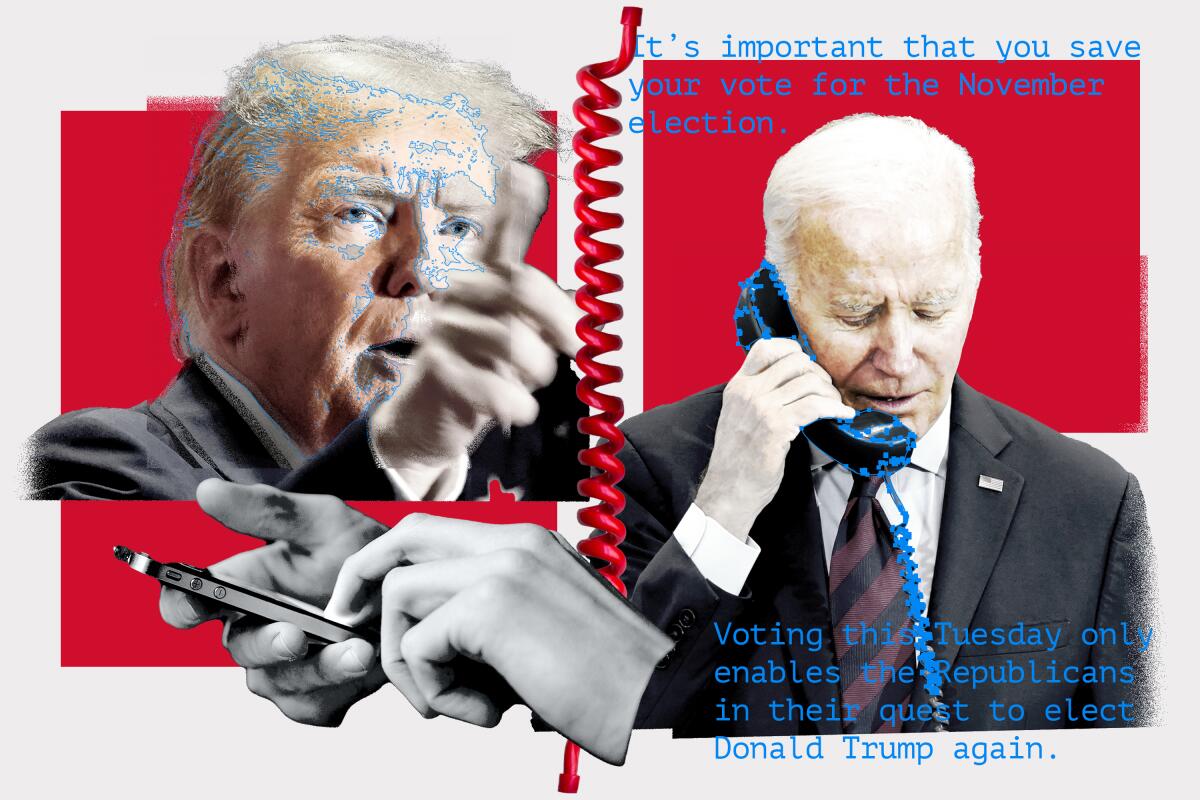

Fast forward to our age of metaverse lies and deceptions, and one might ask similar questions about what’s real and what’s not: Is President Biden on a robocall telling Democrats to not vote? Is Donald Trump chumming it up with Black men on a porch? Is the U.S. going to war with Russia? Fact and fiction appear interchangeable in an election year when AI-generated content is targeting voters in ways that were once unimaginable.

American politics is accustomed to chicanery — opponents of Thomas Jefferson warned the public in 1800 that he would burn their Bibles if elected — but artificial intelligence is bending reality into a video game world of avatars and deepfakes designed to sow confusion and chaos. The ability of AI programs to produce and scale disinformation with swiftness and breadth is the weapon of lone-wolf provocateurs and intelligence agencies in Russia, China and North Korea.

“Truth itself will be hard to decipher. Powerful, easy-to-access new tools will be available to candidates, conspiracy theorists, foreign states, and online trolls who want to deceive voters and undermine trust in our elections,” said Drew Liebert, director of the California Initiative for Technology and Democracy, or CITED, which seeks legislation to limit disinformation. “Imagine a fake robocall [from] Gov. Newsom goes out to millions of Californians on the eve of election day telling them that their voting location has changed.”

The threat comes as a polarized electorate is still feeling the aftereffects of a pandemic that turned many Americans inward and increased reliance on the internet. The peddling of disinformation has accelerated as mistrust of institutions grows and truths are distorted by campaigns and social media that thrive on conflict. Americans are susceptible to and suspicious of AI, not only for its potential to exploit divisive issues such as race and immigration, but also its science-fiction-like wizardry to steal jobs and reorder the way we live.

Russia orchestrated a wave of hacking and deceptions in attempts to upset the U.S. election in 2016. The bots of disinformation were a force in January when China unsuccessfully meddled in Taiwan’s election by creating fake news anchors. A recent threat analysis by Microsoft said a network of Chinese-sponsored operatives, known as Spamouflage, is using AI content and social media accounts to “gather intelligence and precision on key voting demographics ahead of the U.S. presidential election.”

One Chinese disinformation ploy, according to the Microsoft report, claimed that the U.S. government deliberately set the wildfires in Maui, Hawaii, in 2023 to “test a military grade ‘weather weapon.’”

A new survey by the Polarization Research Lab pointed to the fears Americans have over artificial intelligence: 65% worry about personal privacy violations, 49.8% expect AI to negatively affect the safety of elections, and 40% believe AI might harm national security. A poll in November by UC Berkeley found that 84% of California voters were concerned about the dangers of misinformation and AI deepfakes during the 2024 campaign.

More than 100 bills have been introduced in at least 39 states to limit and regulate AI-generated materials, according to the Voting Rights Lab, a nonpartisan organization that tracks election-related legislation. At least four measures are being proposed in California, including bills by Assemblymembers Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland) and Marc Berman (D-Menlo Park) that would require AI companies and social media platforms to embed watermarks and other digital provenance data into AI-generated content.

“This is a defining moment. As lawmakers we need to understand and protect the public,” said Adam Neylon, a Republican state lawmaker in Wisconsin, which passed a bipartisan bill in February to fine political groups and candidates $1,000 for not adding disclaimers to AI campaign ads. “So many people are distrustful of institutions. That has eroded along with the fragmentation of the media and social media. You put AI into that mix and that could be a real problem.”

Since ChatGPT was launched in 2022, AI has been met with fascination over its power to reimagine how surgeries are done, music is made, armies are deployed and planes are flown. Its scarier ability to create mischief and fake imagery can be innocuous — Pope Francis wearing a designer puffer coat at the Vatican — of criminal. Photographs of children have been manipulated into pornography. Experts warn of driverless cars being turned into weapons, increasing cyberattacks on power grids and financial institutions, and the threat of nuclear catastrophe.

The sophistication of political deception coincides with the mistrust of many Americans — believing conspiracy theorists such as Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) — in the integrity of elections. The Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the Capitol was a result of a disinformation campaign that rallied radicals online and threatened the nation’s democracy over Trump’s false claims that the 2020 election was stolen from him. Those fantasies have intensified among many of the former president’s followers and are fertile ground for AI subterfuge.

A recently released Global Risks Report by the World Economic Forum warned that disinformation that undermines newly elected governments can result in unrest such as violent protests, hate crimes, civil confrontation and terrorism.

But AI-generated content so far has not disrupted this year’s elections worldwide, including in Pakistan and Bangladesh. Political lies are competing for attention in a much larger thrum of social media noise that encompasses content such as Beyoncé’s latest album and the strange things cats do. Deepfakes and other deceptions, including manipulated images of Trump serving breakfast at a Waffle House and Elon Musk hawking cryptocurrency, are quickly unmasked and discredited. And disinformation may be less likely to sway voters in the U.S., where years of partisan politics have hardened sentiments and loyalties.

“An astonishingly few people are undecided in who they support,” said Justin Levitt, a constitutional law scholar and professor at Loyola Law School. He added that the isolation of the pandemic, when many turned inward into virtual worlds, is ebbing as most of the population has returned to pre-COVID lives.

“We do have agency in our relationships,” he said, which lessens the likelihood that large-scale disinformation campaigns will succeed. “Our connections to one another will reduce the impact.”

The nonprofit TrueMedia.org offers tools for journalists and others working to identify AI-generated lies. Its website lists a number deepfakes, including Trump being arrested by a swarm of New York City police officers, a photograph of Biden dressed in army fatigues that was posted during last year’s Hamas attack on Israel, and a video of Manhattan Dist. Atty. Alvin Bragg resigning after clearing Trump of criminal charges in the ongoing hush money trial.

NewsGuard also tracks and uncovers AI lies, including recent bot fakes of Hollywood stars supporting Russian propaganda against Ukraine. In one video, Adam Sandler, whose voice is faked and dubbed in French, tells Brad Pitt that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky “cooperates with Nazis.” The video was reposted 600 times on the social media platform X.

The Federal Communications Commission recently outlawed AI-generated robocalls, and Congress is pressing tech and social media companies to stem the tide of deception.

In February, Meta, Google, TikTok, OpenAI and other corporations pledged to take “reasonable precautions” by attaching disclaimers and labels to AI-generated political content. The statement was not as strong or far-reaching as some election watchdogs had hoped, but it was supported by political leaders in the U.S. and Europe in a year when voters in at least 50 countries will go to the polls, including India, El Salvador and Mexico.

“I’m pretty negative about social media companies. They are intentionally not doing anything to stop it,” said Hafiz Malik, professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Michigan-Dearborn. “I cannot believe that multibillion- and trillion-dollar companies are unable to solve this problem. They are not doing it. Their business model is about more shares, more clicks, more money.”

Malik has been working on detecting deepfakes for years. He often gets calls from fact-checkers to analyze video and audio content. What’s striking, he said, is the swift evolution of AI programs and tools that have democratized disinformation. Until a few years ago, he said, only state-sponsored enterprises could generate such content. Attackers today are much more sophisticated and aware. They are adding noise or distortion to content to make deepfakes harder to detect on platforms such as X and Facebook.

But artificial intelligence has limitations in replicating candidates. The technology, he said, cannot exactly capture a person’s speech patterns, intonations, facial tics and emotions. “They can come off as flat and monotone,” added Malik, who has examined political content from the U.S., Nigeria, South Africa and Pakistan, where supporters of jailed opposition leader Imran Khan cloned his voice and created an avatar for virtual political rallies. AI-generated content will “leave some trace,” though, Malik said, suggesting that in the future the technology may more precisely mimic individuals.

“Things that were impossible a few years back are possible now,” he said. “The scale of disinformation is unimaginable. The cost of production and dissemination is minimal. It doesn’t take too much know-how. Then with a click of a button you can spread it to a level of virality that it can go at its own pace. You can micro-target.”

Technology and social media platforms have collected data on tens of millions of Americans. “People know your preferences down to your footwear,” said former U.S. Atty. Barbara McQuade, author of “Attack from Within: How Disinformation Is Sabotaging America.” Such personal details allow trolls, hackers and others producing AI-generated disinformation to focus on specific groups or strategic voting districts in swing states in the hours immediately before polling begins.

“That’s where the most serious damage can be done,” McQuade said. The fake Biden robocall telling people to not vote in New Hampshire, she said, “was inconsequential because it was an uncontested primary. But in November, if even a few people heard and believed it, that could make the difference in the outcome of an election. Or say you get an AI-generated message or text that looks like it’s from the secretary of state or a county clerk that says the power’s out in the polling place where you vote so the election’s been moved to Wednesday.”

The new AI tools, she said, “are emboldening people because the risk of getting caught is slight and you can have a real impact on an election.”

In 2022, Russia used deepfake in a ploy to end its war with Ukraine. Hackers uploaded an AI-manipulated video showing Zelensky, the Ukrainian president, ordering his forces to surrender. That same year Cara Hunter was running for a legislative seat in Northern Ireland when a video of her purportedly having explicit sex went viral. The AI-generated clip did not cost her the election — she won by a narrow margin — but its consequences were profound.

“When I say this has been the most horrific and stressful time of my entire life I am not exaggerating,” she was quoted as saying in the Belfast Telegraph. “Can you imagine waking up every day for the past 20 days and your phone constantly dinging with messages?

“Even going into the shop,” she added, “I can see people are awkward with me and it just calls into question your integrity, your reputation and your morals.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.