William Howell wrote Arizona’s 1864 abortion ban. He modeled it on California’s

It was the era of the Wild West, when white men from back East were flooding into Arizona to reap the golden bounty of the land, take over territories and establish laws.

William Howell, a New Yorker tasked with writing the code that would enshrine Arizona as a territory, cracked open the law books of a neighboring state as a model: California. He copied over swaths of the state’s legal text — including a paragraph that criminalized abortions except when the mother’s life was at risk.

And on Tuesday, 160 years later, Howell’s words rose to relevance again, when Arizona’s Supreme Court ruled that the state would return to the original code on abortion, banning physicians from providing it in all cases except when the mother’s life is at risk.

“History doesn’t happen in a vacuum,” said Melanie Sturgeon, a retired state archivist and co-founder and president of Arizona Women’s History Alliance. “You need to understand what’s going on ... in the territory or state and those next to us, and what’s happening nationally that affects us.”

The Arizona Supreme Court’s ruling Tuesday made abortions illegal, except when a mother’s life is at risk. Attention quickly turned to the November election.

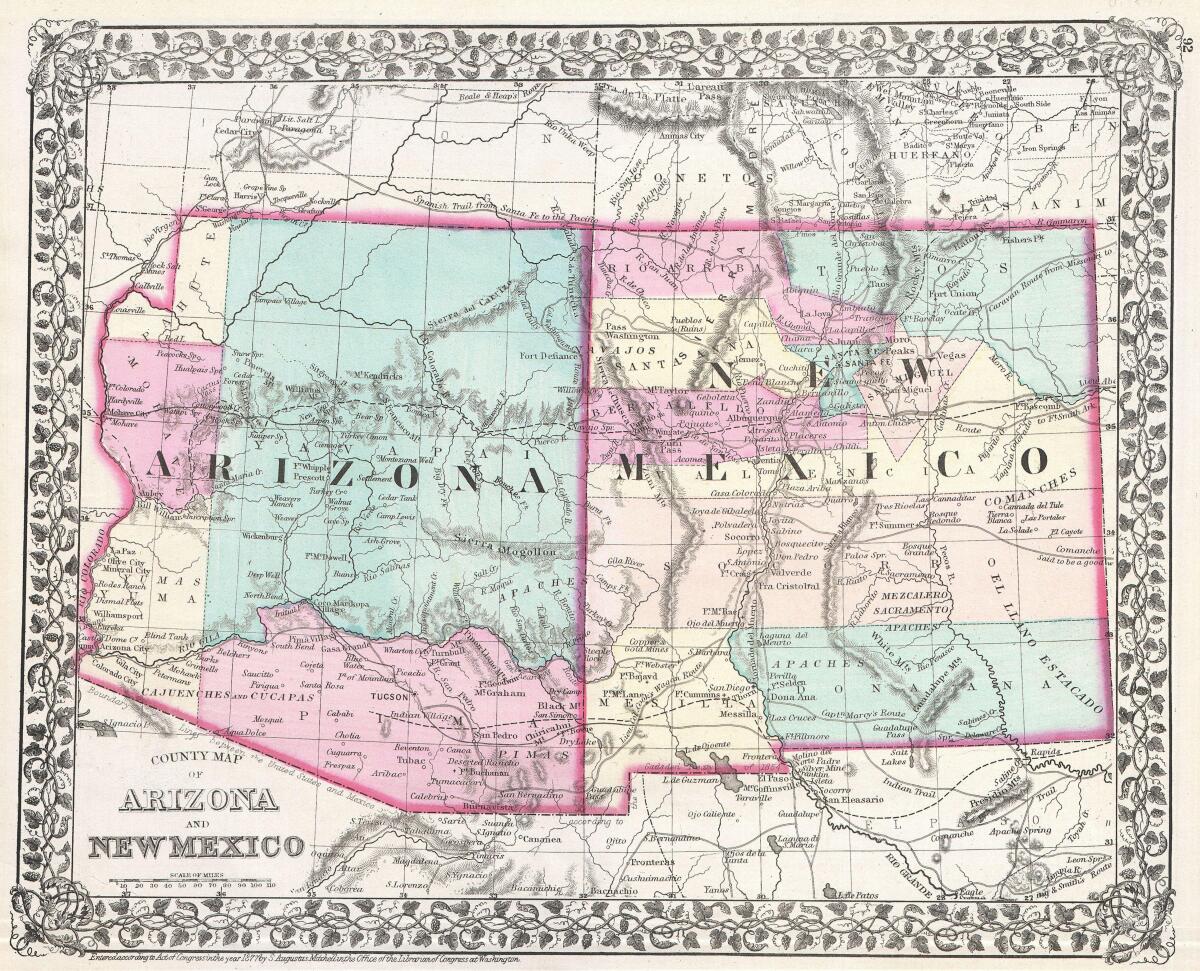

California, with its promises of gold, began attracting a rush of visitors from the East in the late 1840s and quickly coalesced into a state in 1850 — the first in the West. California’s neighbors to the southeast soon followed. In late 1863, Arizona separated from New Mexico to become its own fledgling territory.

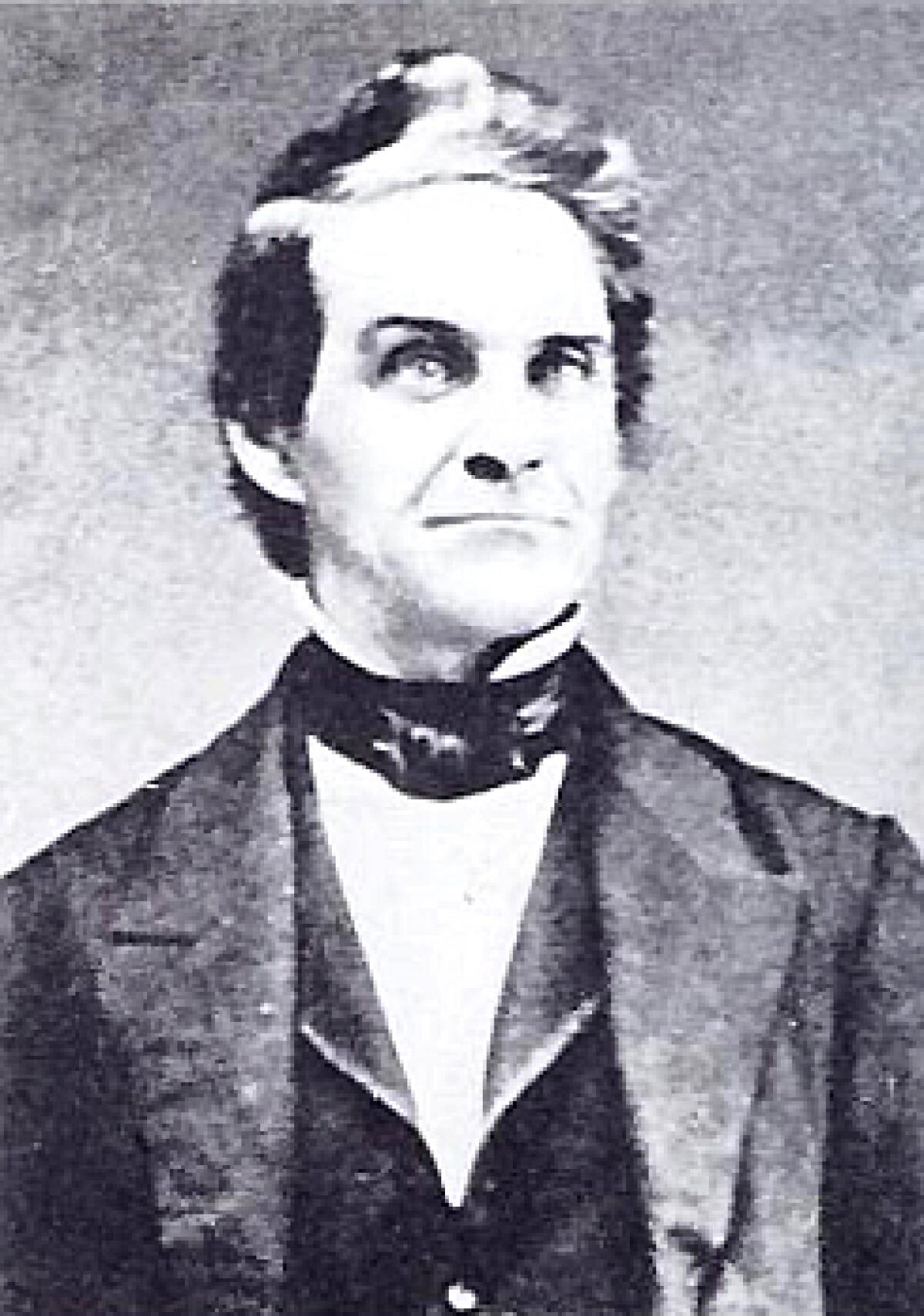

Over the next year, Anglo American men traveled from the East to put together Arizona’s founding structure. Among those key early figures was Howell. Born and raised on a farm in New York, Howell began teaching at 16, became an editor of a newspaper at 19 and by 24 was practicing law, wrote John Goff in his article “William T. Howell and the Howell Code of Arizona.”

Howell was married three times — remarrying after both his first and second wife died — and had children with each of the women, according to Goff. He spent much of his adult life in Michigan, moving up through the ranks of the state Legislature and serving as the speaker pro tem twice before sojourning to Arizona.

“Howell is a rather shadowy figure, not remembered in Arizona, and largely forgotten in his home state of Michigan,” Goff wrote.

In 1862, then-President Lincoln wrote: “When the Arizona Territory shall be organized, let William T. Howell, of Michigan, be appointed as Judge therein.”

Howell moved to Arizona the following year and quickly set up court in Tucson. Amid the Civil War racking the country, Howell delivered a speech to an assembled grand jury that “dwelt at length on the need for the protection of the rights of the people by granting equal justice for all,” Goff wrote.

As one of his first tasks as associate justice in Arizona, Howell “sifted through the statute books of California, New York and other states for laws suitable for the territory,” according to the 1970 book “Arizona Territory, 1863-1912: A political history” by Jay Wagoner.

“Arizona basically ... copied California law,” Sturgeon said.

In California’s laws, Howell found and included — almost word-for-word — its provision on abortion. The paragraph is tucked into a section of Arizona code about punishment for poisoning another person:

“And every person who shall administer or cause to be administered or taken, any medicinal substances, or shall use or cause to be used any instruments whatever, with the intention to procure the miscarriage of any woman then being with child, and shall be thereof duly convicted, shall be punished,” both the California and Arizona codes state, adding that a physician will be excepted from the law “who in the discharge of his professional duties deems it necessary to produce the miscarriage of any woman in order to save her life.”

Howell earned a total of $7,500 for his work on the job, and the honorific of Arizona’s founding document being named “the Howell Code,” according to Wagoner’s book.

“Part of the reason that I think that that becomes a part of the law in the West is to make sure that white women are not having abortions,” Sturgeon said. “I don’t think they care very much if Mexicans and Native Americans had abortions, but they were very concerned.”

The birthrate had been in decline since the beginning of the 19th century, Sturgeon said, as industrialization moved people off farms and into cities, lessening the need for as many children to support their families.

Although modern abortion laws vary from state to state — some including exceptions for rape or incest — Arizona’s original code was strict. That was fairly typical for the time because, Sturgeon noted, the age of consent in Arizona was 10.

“It was just assumed that if you got pregnant as a 10-year-old, that you had seduced that uncle, that next-door neighbor, that older brother or whatever,” she said. “And so there’s nothing in our laws about rape or incest.”

Sturgeon said she has read court transcripts of judges and juries interrogating children about their role in attracting an older man.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the LAPD’s abortion squad hunted down women getting the procedure and the people performing them.

“There’s a poor child who carries a baby to term ... that has all this trauma of being molested and impregnated by a relative or a family friend, and they have to live with that for the rest of their life,” she said, “because it was just assumed that they were the ones to seduce someone.”

Not long after Arizona’s code was established, advertisements for self-administered abortions started popping up in newspapers, Sturgeon said. The advertisements used the same term as the Arizona code — “medicinal substances” — to signal abortions.

“Anytime you saw an advertisement that said ‘Portuguese medication,’ that was a euphemism for ‘This will produce an abortion,’” she said.

Howell’s stay in Arizona did not last long. As Goff writes, Howell received word that his third wife had also fallen ill in Michigan, “and might not live until the judge got home.” Howell took a leave of absence from his work in Arizona to return to his dying wife’s side.

He probably never returned West.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.