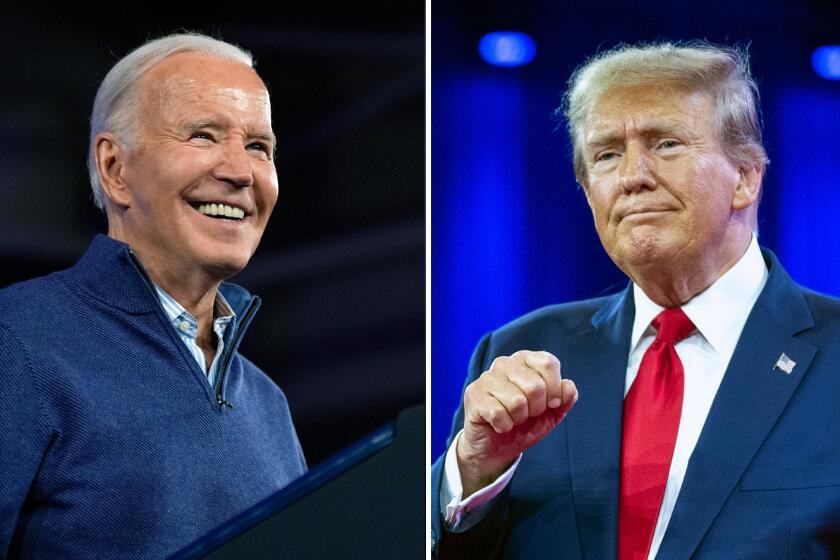

Column: Biden’s big speech didn’t move the needle, nor have rising wages. But these 3 things might

WASHINGTON — Two weeks after President Biden’s State of the Union address, it’s clear the speech hasn’t shifted the presidential race.

Much as they did before the speech, polls show a very close contest: Biden leads by 1 point in a new survey by YouGov for the Economist, former President Trump leads by 1 point in an Ipsos survey for Reuters, the two are tied in the latest from Morning Consult, and so on. And Trump continues to lead by small amounts in most polls of the swing states likely to decide the election.

Should Democrats panic?

No. Speeches seldom move the world, except in movies. State of the Union addresses, in particular, tend to draw viewers who already have their minds made up. Biden’s energetic performance fired up Democratic partisans, but the vast majority of swing voters didn’t watch it.

The greater concern for Biden may be that his job approval numbers haven’t budged, even as rising wages and falling inflation have started to make Americans less gloomy about the economy.

As political scientists John Sides of Vanderbilt University and Michael Tesler of UC Irvine wrote this week, “at this early date, approval ratings actually predict the eventual outcome better than polls do.” Approval of Biden has been mired for most of the last year at about 40% — well into the danger zone.

What might change that? The answers fall into three broad categories: Over the next seven months, voters could begin feeling better about the country; a larger share of them could begin to warm to Biden; or the president could win votes from people who disapprove of him. None of those are guaranteed, but each remains plausible.

State of the Union addresses seldom matter much. This one did: It was Biden’s first big opportunity to convince voters that he’s still up to the job.

Improving views of the U.S.

I’ve written before about the big disconnect between voters’ negative views of the economy and the positive picture painted by economic statistics. With unemployment near a 50-year low, inflation down and wages up, pessimism has started to abate, but it continues at a level that puzzles a lot of economists.

The most likely explanation is that even though prices have stopped their rapid rise, everyday goods and services — gas, groceries and rent — remain a lot costlier than they were a couple of years ago. Average wages have risen faster than prices over the last year, but many families remain pinched.

You are reading our Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The hope for Democratic strategists is that voters’ negative feelings about the economy result mostly from a time lag — and that memories of the rapid inflation of 2022 and early 2023 will soon fade. And indeed, measures of consumer confidence have improved compared with last year‘s findings, but that has yet to lead to warmer voter assessments of Biden.

A similar argument applies to crime: Last year saw what appears to be “by far the largest one year decline in murder ever recorded,” crime data analyst Jeff Asher wrote after the FBI released preliminary 2023 crime numbers this week. (Comparable U.S. crime data goes back to 1960.) A few cities, including Washington, D.C., and Memphis, Tenn., bucked the trend, but in most of the country, the murder rate has come close to erasing the spike that took place during the COVID-19 years.

Overall violent crime levels have done even better — they’re now down to levels last seen in the mid-1960s.

Yet much of the public still thinks the U.S. is in the midst of a crime wave.

Some of that has to do with partisanship, and some with media coverage of rare but spectacular crimes — shootings on the New York subway, for example. But as with the economy, some of the gap between perception and reality involves time lags. Continued improvement could lead to more positive views.

Polls get things right most of the time, but problems crop up, generating headlines. How to tell the good from the bad, and how L.A. Times polls did this year.

Typically, as Sides and Tesler wrote, a president’s approval numbers go up at least a few points during an election year. That was true for Presidents Nixon, Clinton and Obama, and it shouldn’t be a surprise: Incumbent presidents typically can raise huge amounts of money to advertise their achievements.

Improving views of Biden

Biden definitely fits into that pattern in fundraising. Between his principal campaign account and the Democratic National Committee, the Biden team started March with $98 million in the bank, according to financial disclosure reports, compared with $38 million for Trump’s side. Additional committees affiliated with Biden bring cash on hand to $155 million, the campaign says, and they’ve launched a big spring advertising effort in swing states.

A key audience is Democrats who plan to vote for a third-party candidate or stay home. Polls indicate that Biden is drawing support from about 80% to 85% of Democratic voters, while Trump gets backing from more than 90% of Republicans. Evening that disparity would put Biden in better shape.

In swing states, where Biden doesn’t have a big Democratic cushion to protect him, the impact of independent and third-party candidates could be enough to swing the outcome to Trump.

Winning over the disapprovers

Even if some improvements take place, the odds are that Biden will have historically low approval levels when he faces voters in November.

White House and campaign officials profess a lack of concern: Although “historically, favorability and vote choice have been correlated,” Biden advisor Jennifer O’Malley Dillon said in a recent interview with the New Yorker, “I actually think that’s no longer the case.”

Democratic aides cite the results of the 2022 midterm election. According to exit polls, Democratic candidates won a small majority of voters who said they “somewhat disapprove” of Biden.

The reason for that is simple: Those voters also disapprove of Trump.

Former President Trump is bashing California in his 2024 campaign; if he wins he wants to force it to change — on environment, immigration, LGBTQ issues and more.

That’s why the campaign likely will focus heavily on the “double disapprovers” — Americans who dislike both Biden and Trump.

About 1 in 4 U.S. adults falls into that category, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of data from a survey of 12,693 adults conducted Feb. 13-25. (The share is a bit smaller among adults who vote — closer to 1 in 5, according to national data from Marquette University in Wisconsin.)

Those double disapprovers are disproportionately young — 41% of Americans aged 18 to 29 view Trump and Biden negatively, compared with 15% of those older than 65, Pew found. These disapprovers are also more common among Latino and Asian Americans than either their white or Black counterparts.

Another significant group among the disapprovers: people who voted for Nikki Haley in Republican primaries. Just over half of voters who backed her disapproved of both Trump and Biden, Pew found.

Biden and Trump offer converging narratives about the country: one optimistic, one apocalyptic. That collision is the core of the 2024 election.

But dislike of Trump isn’t as intense or as widespread as it was in 2020.

A Suffolk University poll taken in early March for USA Today found, for example, that approval of Trump’s performance in office is now higher than it was during his tenure. That’s an example of how nostalgia tends to improve presidential ratings after the fact, but also of how Trump currently benefits from the retrospective glow of the relatively good economic times of his first three years in office.

To counter that bump, Democrats are deploying a two-pronged approach that’s already visible in Biden’s campaign. One prong involves reminding voters of the chaos of the Trump years, which culminated in his supporters’ attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021,. in an effort to block Congress from finalizing election results showing he’d lost. Republicans counter with attacks on Biden’s age.

The other prong is more ideological: On both sides of the aisle, double disapprovers most often identify as moderates, polls show.

In 2016, a key reason Trump won was that voters, on average, viewed him as closer to the political center than his Democratic opponent, Hillary Clinton. Once in office, of course, Trump hewed to the right, losing that moderate advantage. This time around, he has tried to regain it on at least some issues — refusing to publicly say what sort of abortion ban he might support, for example, and attacking Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis over his past support for cuts to Medicare and Social Security.

A major effort of Biden’s campaign aims to convince voters that a reelected Trump would, once again, try to govern from the right — not just on immigration, where Trump has openly called for mass deportations, but on issues like healthcare, abortion rights and Social Security.

With Biden and Trump both so well-known, the number of undecided voters in 2024 may be smaller than ever, but the classic formulation of American politics still holds true: Winning requires capturing the center.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.