Column: Congress has left Ukraine in the cold. The consequences will be dire if aid isn’t renewed soon

WASHINGTON — Ukraine’s war to repel Russia’s invasion suffered two major setbacks this year.

The first was on the battlefield, where a long-promised Ukrainian ground offensive was stymied by Russian fortifications that were stronger than expected.

The second is underway in Washington, where Republicans in Congress have held up President Biden’s request for $61 billion to keep Ukraine’s war effort going in 2024.

The battlefield setback was a painful disappointment for Ukrainian leaders, who hoped the offensive could turn the tide of the war.

The political problem could be even worse. If U.S. funding isn’t approved quickly, aid from Europe could dry up as well, and Ukraine’s ability to fight could erode dramatically.

Trump’s opponents have succeeded in getting to the U.S. Supreme Court with their argument the 14th Amendment disqualifies him from the ballot. But they face hurdles.

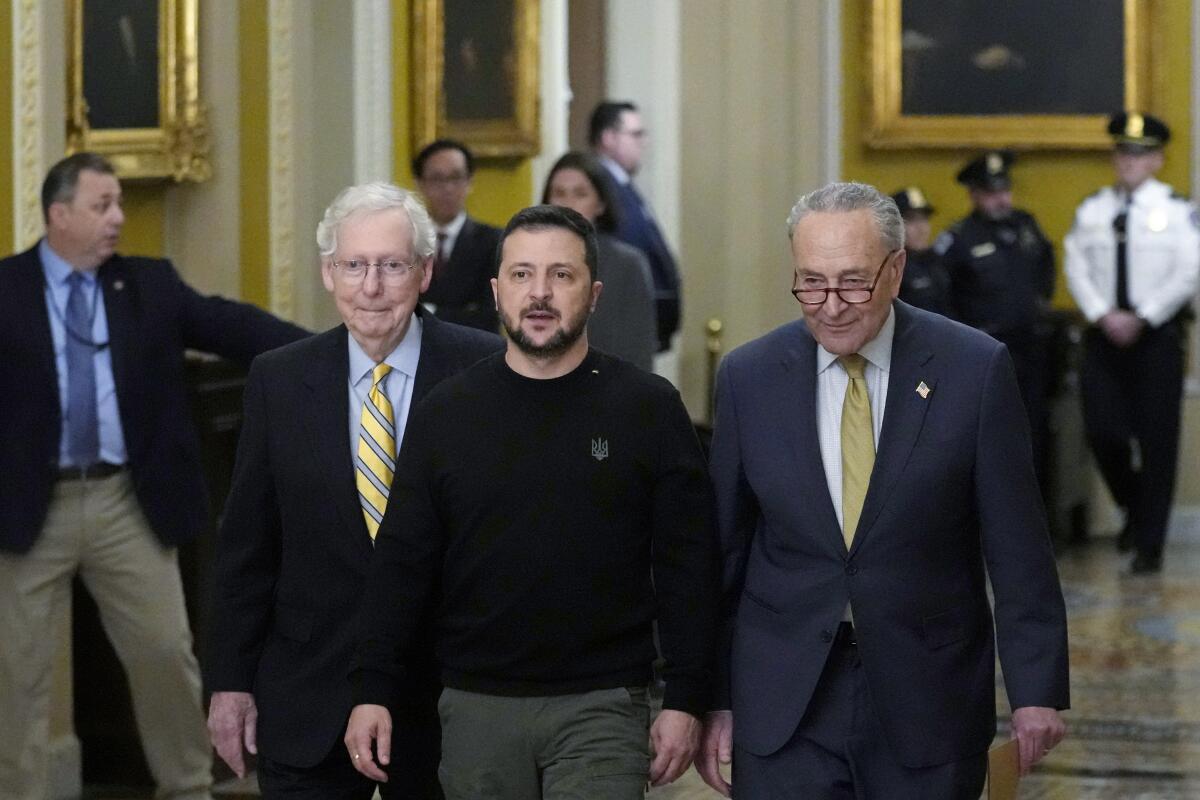

Andriy Yermak, chief of staff to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, told an audience in Washington that if the deadlock persists, it will create a “big risk to lose this war.”

His warning was for naught. Republican leaders in both houses of Congress say they support helping Ukraine in principle, but they‘re holding the aid hostage to bargain for tougher immigration rules, especially toward asylum seekers. .

The House of Representatives went home 10 days before Christmas without acting on the administration’s request. Senate negotiators from both parties stayed behind last week to try to strike a deal, but they fell short, too.

As a result, Ukraine doesn’t know whether it can count on more funding for the artillery shells and air defense weapons it needs to defend its cities from Russian onslaught.

Military experts say Ukraine’s armed forces can keep fighting until the end of January with ammunition they already have. But the uncertainty over future supplies has forced them to scale back operations and reduce their rate of artillery fire.

The challenge for Biden and his campaign strategists is how to persuade unhappy voters not only that better times are ahead, but that he deserves some credit.

“A lower level of resources is going to mean a lower chance of success,” said Michael Kofman, a military analyst at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “The effect of delayed funding … will result in tangible deficits at the front line.”

There’s a broader political impact, too.

If Congress doesn’t approve funding quickly, the lesson to other countries will be that domestic politics has made the United States an unreliable ally.

For almost two years, Biden promised that the United States would support Ukraine “as long as it takes,” and urged other governments to do the same.

This month, faced with pushback, he downsized the commitment. Now it’s “as long as we can.”

“If Congress passes new funding by the end of January, it won’t be a major blow to our credibility,” said Alexander Vershbow, a former U.S. ambassador to Moscow. “But if it drags on for months, it will be a disaster.”

GOP leaders said their decision to delay the funding was ordinary legislative hardball — a bargaining chip to win concessions on immigration, which most voters consider more important than Ukraine. But their willingness to stiff-arm Zelensky also reflected eroding support among GOP voters for Ukraine’s battle against Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Polls show most Americans support helping Ukraine at current or higher levels of aid. But conservative Republican voters — the ones most likely to turn out for primary elections — are disproportionately opposed.

Last month, Democrats appeared deeply divided over President Biden’s handling of the Israel-Hamas war. But as Biden’s diplomacy has evolved, that problem has ebbed.

The logjam has left Ukraine in the cold, literally and figuratively.

The Ukrainians’ short-term military goal is to survive Russia’s winter offensive, which is likely to focus on civilian targets such as cities, electrical power plants and other economic infrastructure.

After that, the Ukrainians hope to use long-range missiles supplied by the U.S. and other countries plus home-grown drones to strike Russian targets.

In a recent interview with the Economist, Ukraine’s military commander, Gen. Valery Zaluzhny, called the situation a “deadlock,” adding that trench warfare does not favor Ukraine in the long run.

Without a technological breakthrough, he warned, “Sooner or later, we are going to find that we simply don’t have enough people to fight.”

In some wars, a deadlock might open the way for peace negotiations. Not this one.

At his four-hour-long news conference Dec. 14, Putin buoyantly declared: “Victory is ours.”

One reason for his confidence, he said, is how shaky Ukraine’s Western support appears.

Ukraine is “getting everything as freebies,” he said. “But those freebies can run out at some point, and it looks like they’re already starting to run out.”

He did not sound interested in seeking a compromise settlement. “There will be peace when we achieve our goals,” he said.

Those goals, he added, include replacing Zelensky’s government and disbanding Ukraine’s armed forces.

He doesn’t sound ready to give up his ambition to absorb Ukraine into Russia.

Our aid to Ukraine isn’t an act of charity. It’s in our interest to prevent Putin from expanding his empire.

Putin still thinks he can wait out the West — that the United States and Europe will tire of helping Ukrainians defend themselves and walk away.

The grim lesson of the last few weeks is that he may turn out to be right.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.