News Analysis: It’s not just Feinstein. McConnell episode highlights age, vulnerability of U.S. leaders

WASHINGTON — California Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who has faced questions in recent years about her mental capacity and fitness for office, got some unwelcome company in the health spotlight this week.

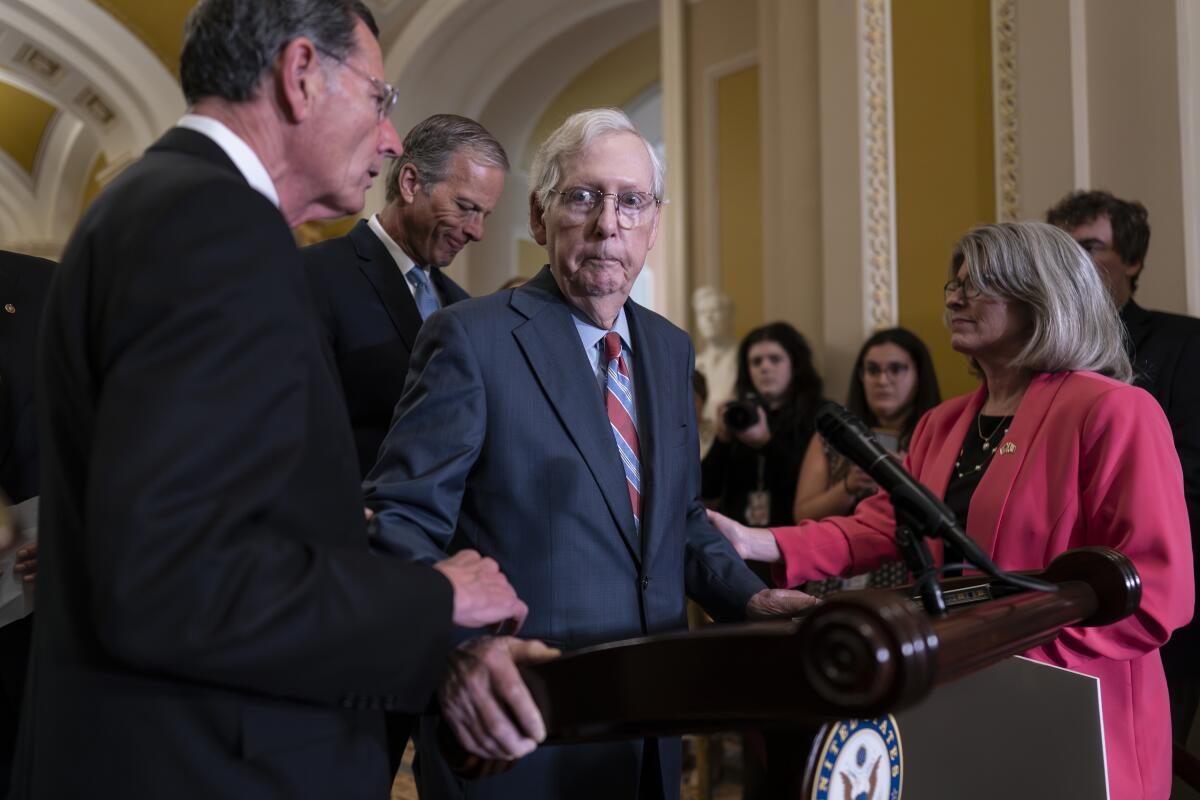

In a moment that cast a grim light on America’s aging leadership, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) froze midsentence while opening his weekly news conference Wednesday, standing unblinking with his mouth pursed for a full 20 seconds before his colleagues escorted him away from the microphones and Sen. Joni Ernst (R-Iowa) crossed herself.

McConnell, 81, is not much older than President Biden or former President Trump. A severe health crisis for any of them could change the direction of the nation. But none of America’s oldest leaders show any signs of stepping away anytime soon, despite a long history of lawmakers who can’t resist running for just one more term and end up remaining in office through physical and mental decline.

Age isn’t just a number. The older people are, the more likely they are to face health problems. And McConnell’s scary moment wasn’t the only sign this week of the risks of electing — and reelecting — aged lawmakers.

Feinstein, the Senate’s oldest member at 90, has repeatedly appeared confused and forgetful since she returned to the Senate in May after an extended stretch away to recover from a bad bout with shingles. Feinstein’s office said she would return to California for the Senate’s August recess; she had declined to travel home over lawmakers’ Fourth of July break.

But her recent performance won’t alleviate concerns about her mental fitness.

On Thursday morning, Feinstein attempted to deliver a speech when it was her turn to state her vote during a standard roll call on the Senate Appropriations Committee. As she began to read from prepared remarks in support of an amendment, an aide quickly jumped in to interrupt her, whispering into her ear as committee Chair Patty Murray (D-Wash.), seated next to Feinstein, repeatedly told her to “just say, ‘Aye.’”

“OK. Just ...” a confused-looking Feinstein began to ask Murray. “Aye,” Murray replied with a thumbs-up. Feinstein declared, “Aye,” with a chuckle.

Not long afterward, as an aide wheeled her to the Senate floor for votes there, I approached and asked Feinstein whether she had any thoughts on McConnell’s apparent health scare.

“No? Healthcare?” she asked.

Feinstein may have misheard or misunderstood the question, so I began to explain what had happened with McConnell at Wednesday’s news conference — a topic that was the central focus of most senators’ and reporters’ conversations on Capitol Hill on Thursday.

“I didn’t know that. I didn’t see that,” she said.

An aide jumped in. “I don’t know if I gave you an update on that, Senator, so I’ll give you an update. It was happening when there were some votes happening,” the aide said.

“Oh, I know what you —” she interjected. “Well, I wish him well. He’s a strong man and this is really when that kind of strength comes in. So: Say a prayer, cross my fingers, do it all.”

The aide then wheeled her onto an elevator.

Before Trump, Ronald Reagan was the country’s oldest president, leaving office just before his 78th birthday. He’d joked about his age during his reelection campaign, saying during a 1984 debate with Democratic challenger Walter F. Mondale, 56, that he was “not going to exploit, for political purposes, [his] opponent’s youth and inexperience.”

Reagan announced in 1994, nearly six years after leaving office, that he had Alzheimer’s disease. One of Reagan’s sons has said that his father started showing signs of the disease’s effects on his cognition before his second term had begun, and CBS News reporter Lesley Stahl has recalled Reagan seemingly glazing over and not remembering her during a meeting in 1986, more than two years before he left office.

But Reagan was young compared with how old Biden or Trump would be during a second term if one is reelected in 2024.

Biden, 80, is already the oldest president in U.S. history, and if reelected he’ll be expected to serve until he’s 86. Trump, now 77, leads early polls for the Republican nomination to challenge Biden in 2024.

Biden retains the traces of a childhood stutter and has long been prone to gaffes or verbal stumbles. But the president renewed concerns about his health last month when he tripped over a sandbag onstage at the Air Force Academy’s graduation ceremony in Colorado.

In the weeks since the episode, Biden has repeatedly used the shorter staircase when boarding Air Force One and has kept a lighter evening schedule than most presidents. He faced criticism for skipping a dinner during the NATO summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, earlier this month as well as a dinner with foreign leaders during the Group of 20 summit in Bali, Indonesia, in November.

Dr. Kevin O’Connor, the president’s physician, said in February that Biden “remains fit for duty, and fully executes all of his responsibilities without any exemptions or accommodations.”

Still, questions surrounding his age have dogged Biden, and Republicans have highlighted every miscue and stumble.

In a June NBC poll, 68% of registered voters said they had major or moderate concerns about Biden’s mental and physical fitness to serve as president, compared with 55% who said the same of his potential rival Trump. Only 33% of U.S. adults said they think Biden is in good enough physical shape for the office, while 64% said the same of Trump.

Republicans have been making hay out of Biden’s age and sharpness since the 2020 presidential campaign, and last year dozens of House Republicans sent an open letter demanding that he take a cognitive test.

Some of Trump’s rivals for his party’s nomination have tried to make an issue of his age — but those efforts appear to have gained far less traction among the aging Republican electorate expected to vote in next year’s GOP primary contests.

“America is not past our prime — it’s just that our politicians are past theirs,” former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley said during her campaign launch early this year, before calling for “mandatory mental competency tests for politicians over 75 years old.”

Many younger lawmakers are clamoring for a more robust generational change. But that doesn’t mean they’re thrilled to talk about it.

“I would just say that our greatest generation loves to serve — and we are grateful for their service,” Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), 56, said with a tight grin when asked about her aged colleagues.

Although Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.), age 43, opposed McConnell’s reelection as Senate Republican leader and has called for a generational change in the GOP, he stressed that his opposition to McConnell wasn’t about the leader’s age or health.

Is age a problem for Trump and Biden?

“It’s true. Our leadership is very old,” Hawley said. “It’s a problem for the current occupant of the White House, clearly.”

Has age impacted Trump?

“Not that we’ve seen right now, but what is he, 78?” Hawley told The Times, overestimating the former president’s age. “I mean, just as a factual matter, all of these guys are old.”

Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Fremont), 46, one of the few California Democrats who has called for Feinstein to step down, said young people “want a new generation of leadership.”

“After Biden beats Trump, there will be a needed clearing-out of politicians who have clung to their positions for decades, and a chance for bold, imaginative, dynamic leaders to solve problems that have plagued us for decades,” he said.

But Khanna is backing 77-year-old Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Oakland) in next year’s race for the Senate seat Feinstein plans to leave when her term ends in January 2025; and he was a national co-chairman on the 2020 presidential campaign of Sen. Bernie Sanders, now 81.

Khanna said that supporting Biden is necessary to beat Trump.

“With the threat of Trump’s return — one of the biggest brands in modern American life — Democrats know we need a brand Americans trust to win, and that’s why we are going to support Biden and not gamble on the new thing,” he texted The Times.

“Do I believe it’s time for generational change? Yeah, I do,” said Rep. Chip Roy (R-Texas). “Leadership from the baby boomer generation and shortly thereafter has been in charge for a helluva long time. And I mean, honestly, they’ve been screwing up the country long enough.”

Roy, 50 and a member of the subsequent Generation X, said that is part of the reason he’s one of the few Republican lawmakers who have endorsed Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, 44, for president instead of Trump.

But lawmakers in Congress largely remain delicate when discussing age, given the sensitivities of the issue and their personal relationships with elder colleagues.

“Whether it’s Sen. McConnell, whether it’s Sen. Feinstein or anybody else, it’s a very individual decision to continue to serve or ... step away,” said Sen. Alex Padilla (D-Calif.), a former member of Feinstein’s staff.

McConnell, the longest-serving party leader in Senate history, returned to the microphones for a few minutes on Wednesday after his freeze-up, and insisted, “I’m fine.” He told reporters that he’d felt lightheaded.

He spoke on the Senate floor later that day and was at work on Thursday. He later told reporters that Biden had called him to check in, and joked that he told Biden, “I got sandbagged” — a reference to Biden’s fall at the Air Force Academy graduation.

McConnell suffered a bad fall of his own in March, and was hospitalized for a concussion and fractured rib. He was absent from the Senate for six weeks.

He has also reportedly had other recent falls, including one during a trip to Finland in February and another at Reagan National Airport outside Washington two weeks ago. He reportedly got up and continued on with his day after both falls.

A survivor of childhood polio, McConnell has long walked slowly and cautiously. But since his return to the Senate this spring, he has moved more slowly, occasionally using a wheelchair.

One of his aides pointed out that McConnell had delivered a floor speech after Wednesday’s news conference, but declined to say whether the episode was connected to McConnell’s earlier fall, or to tell The Times whether the GOP leader had seen a doctor since the news conference.

Until recently, the House was another bastion of gerontocracy. But last year, then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco), 83, and her octogenarian deputies, Steny H. Hoyer (D-Md.) and James E. Clyburn (D-S.C.), stepped down from leadership. Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.), 52, Katherine Clark (D-Mass.), 60, and Pete Aguilar (D-Redlands), 44, took over.

“What we have seen in the leadership from Speaker Pelosi and Leader Hoyer and Jim Clyburn has been helpful to the Democratic Caucus, and I think it’s been viewed incredibly positively by the members,” Aguilar told The Times. “We revere and hold up the work that they have done and continue to do. But, you know, we have benefited from a Leader Jeffries at this moment.”

Still, there isn’t a direct line between age and health.

Freshman Sen. John Fetterman (D-Pa.), 53, suffered a stroke just days before the Democratic primary during his 2022 run, and has since been treated for depression. Then-Sen. Mark Kirk (R-Ill.) had a stroke at age 52 that sidelined him from work for almost a full year in 2012.

And not every octogenarian has slowed down. Sanders, the Senate’s third-oldest member, seems just as sharp in conversations as when he first won a race for Congress in 1990, two years before Feinstein’s election to the Senate.

Sanders told The Times that he hoped voters would “look at the whole individual, not just age.”

“Age is a factor. Experience is a factor. Most important is what your views are and what you’re doing for your constituency,” he said. “Age is one of many factors that should be taken into consideration, but I hope we don’t become an ageist society.”

But the risk of major medical problems rises dramatically with age — including those that affect cognitive ability.

Multiple senators of both parties said that McConnell had seemed normal in interactions on Wednesday night and Thursday morning.

Sen. Charles E. Grassley (R-Iowa), at 89 the second-oldest member of the Senate, said he’d talked with McConnell at almost 10 p.m. Wednesday, and hadn’t seen any signs that he was struggling. He dismissed questions about whether the GOP leader’s age should be a concern.

“I’m a rising 90-year-old,” Grassley said with a smile as he walked with a slight limp to the Senate floor. “Age is just a number.”

Congress has a long history of lawmakers sticking around well past their primes.

Sens. Strom Thurmond (R-S.C.), 100, and Robert C. Byrd (D-W.Va.), 92, both died in office earlier this century after years of declining physical and mental health. Massachusetts’ Sen. Edward M. Kennedy’s death at age 77 in 2009 cost Democrats uncontested control of the Senate and stalled President Obama’s legislative agenda.

And Mississippi GOP Sen. Thad Cochran’s cognitive decline was a campaign issue in his 2014 primary. Days after he won that race at age 76, he got lost on the way to the Senate’s weekly Republican lunch, tried to walk into the Democrats’ lunch instead, then needed my help to find the room he’d visited countless times before — which was just around the corner. Almost four more years passed before Cochran retired. He died soon after at 81.

Times staff writers Courtney Subramanian and Owen Tucker-Smith contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.