California tried and failed to ban for-profit ICE detention centers. What does that mean for other states?

WASHINGTON, D.C. — California’s landmark ban on private prisons and immigrant detention facilities saw its fate sealed when a federal court officially repealed the 2020 law.

In a win for private prison contractors, a final judgment last month declared Assembly Bill 32 unconstitutional as applied to private detention contracts for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and other federal agencies, though the ban remains in place for private prisons in the state.

The ban was enacted amid mounting reports of unsafe conditions and health violations at detention facilities, including moldy food, overuse of solitary confinement and dangerous delays in medical care. Following a 2020 investigation by The Times into violence against detainees at California’s privately run federal immigration detention centers, the newspaper sued the Department of Homeland Security for records of abuse nationwide.

After taking stock of California’s lost court battle, advocates and lawmakers in other states have altered proposed legislation that would apply restrictions on immigrant detention in hopes that scaled-back measures will face fewer political hurdles.

“AB 32 was introduced at the height of the Trump era, when there was an attempt to aggressively expand immigration detention through private corporations,” said Jackie Gonzalez, policy director of Immigrant Defense Advocates, who advised legislators drafting the bill. “We pushed really hard.”

The news comes as detention facility operators face an increase in numbers of detained immigrants with last month’s expiration of pandemic-era border restrictions under Title 42. Nearly 30,000 immigrants were detained as of June 18, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a nonpartisan research center at Syracuse University, up about 40% from a month prior. DHS cleared detention space ahead of Title 42’s expiration and, according to TRAC, there are signs the numbers are stabilizing.

Concerns over conditions in detention facilities have continued to grow. On May 17, an 8-year-old girl died in Border Patrol custody in Texas after a nurse practitioner allegedly denied her mother’s requests for an ambulance and officials at the facility complained about the “overuse of hospitalization.”

People in ICE detention are not serving time for crimes but are held while an immigration judge decides if they should be deported. Detention levels peaked at more than 55,000 under the Trump administration and dropped in 2021, amid the pandemic, to a low of 13,000.

After Gov. Gavin Newsom signed AB 32 in October 2019, the Trump administration rushed to preempt the law before it could take effect.

Last week, lawyers now representing the Biden administration urged a panel of judges on the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals to repeal the law.

AB 32 would have prohibited new contracts and phased out existing private detention facilities by 2028. But days before it could take effect on Jan. 1, 2020, ICE established new contracts of up to 15 years, totaling nearly $6.5 billion, with three private prison companies that already operated private detention centers in the state: the GEO Group, CoreCivic and Management & Training Corp. The new contracts also added three facilities, nearly doubling immigrant detention capacity in California to about 7,200 beds.

Immigrant detention facilities in California

Otay Mesa Detention Center, operated by CoreCivic. Capacity: 1,994

Mesa Verde ICE Processing Center, operated by GEO Group. Capacity: 400

Golden State Annex, operated by GEO Group. Capacity: 700

Central Valley Annex, operated by GEO Group. Capacity: 700

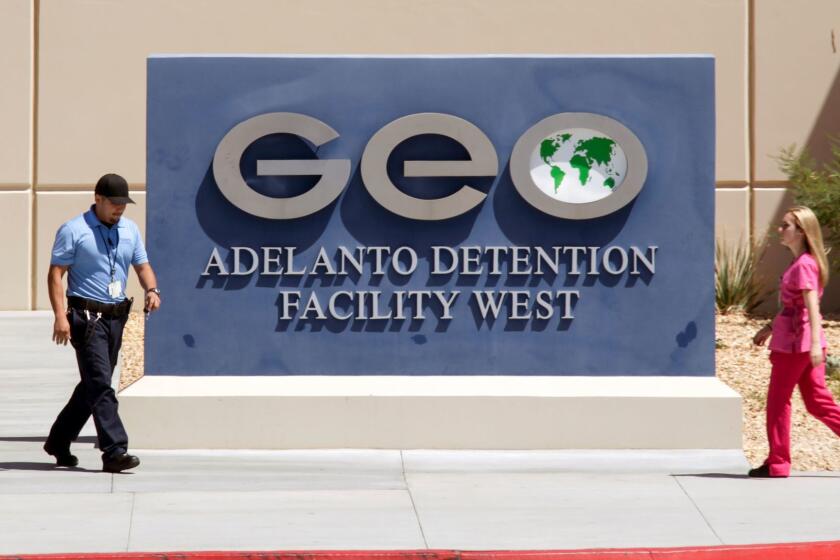

Adelanto ICE Processing Center, operated by GEO Group. Capacity: 1,940

Desert View Annex, operated by GEO Group. Capacity: 750

Imperial Regional Detention Facility, operated by Management & Training Corp. Capacity: 704

The GEO Group and the Trump administration sued California, arguing that the ban undermined the federal government’s ability to enforce immigration law. Neither the GEO Group nor DHS responded to requests for comment from The Times.

The GEO Group had plenty to lose. According to the lawsuit, it would have forfeited an average of $250 million a year in revenue if its facilities had been forced to close.

Several jails in California once held immigrants for ICE. But in 2017, California became the first state to pass a law preventing local governments and law enforcement agencies from signing new contracts with the federal government or private corporations for immigrant detention. Yuba County Jail’s $8.6-million-a-year contract, the only remaining detention contract between ICE and a local law enforcement agency, ended Feb. 8.

Rep. Zoe Lofgren of San Jose was among 24 California Democratic members of Congress who sent a letter to ICE last year urging it to stop holding immigrants at the Yuba jail and two private facilities in the state based on violations such as failure to investigate staff misconduct, the discovery of nooses hanging in detainee cells and misuse of a chemical disinfectant spray that left detainees with chronic nosebleeds and headaches.

J. Lee, 41, said he was sexually assaulted by another detainee in 2020 at the GEO Group’s Adelanto ICE Processing Center near San Bernardino after overstaying his tourist visa from South Korea. He worries that more detainees will suffer with private prisons in continued use. (The Times does not name victims of sexual abuse unless they volunteer to be publicly identified.)

A Times investigation found that since 2017, at least 265 calls have reported violence and abuse inside California’s four privately run immigrant detention centers. Half of them alleged sex crimes against detainees.

“I still have nightmares about what happened there,” said Lee, who is now married to a U.S. citizen and lives in Orange County.

Records disclosed to Lofgren, who is chair of the House Judiciary immigration subcommittee, obtained by Immigrant Defense Advocates and reviewed by The Times, indicate that ICE and GEO executives communicated about the effect of AB 32 on detention in California. Also disclosed was a 2018 ICE proposal for additional detention space in the San Francisco region, which called the reduction of beds due to California legislation “a devastating blow to the ongoing ICE mission.”

ICE owns and operates only a handful of detention facilities around the country. The private prison industry is a multibillion-dollar enterprise in the U.S., and its facilities hold 80% of ICE detainees.

Several private prisons housing California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation inmates closed around the time AB 32 became law, though three were repurposed as ICE facilities under the contracts signed in late 2019.

Just after taking office, President Biden signed an executive order phasing out federal use of private prisons. But the order didn’t cover immigration detention.

Then, to the surprise of immigrant advocates, the Biden administration picked up where Trump officials left off on the lawsuit against California’s private prison ban. Last year, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the ban violated the U.S. Constitution’s supremacy clause, which precludes states from interfering with the enforcement of federal laws.

Izzy Gardon, a spokesman for Newsom, called the outcome disappointing.

“When California became the first state in the nation to ban private for-profit prisons, we set a new goalpost for justice,” he said. “History will not look kindly on this industry that commodifies individuals and routinely violates basic human rights.”

Sharon Dolovich, a professor and director of the Prison Law & Policy Program at UCLA, said the 9th Circuit’s ruling should prompt lawmakers to strengthen regulations for all types of jails and prisons, such as increased transparency and healthcare requirements.

“If people in this state care about reducing the opportunity for prison administrators to hold people in inhumane conditions of detention, they should care as much about publicly run facilities as they do about privately run facilities,” she said.

Three main types of ICE detention contracts

Intergovernmental service agreements (IGSA): ICE contracts with local governments to detain people in jails or dedicated ICE facilities. Local governments can contract with private prison companies to operate the facilities.

Contract detention facilities (CDF): ICE contracts directly with private prison companies to detain people in facilities owned and operated by the companies.

Service processing centers (SPC): Facilities owned by ICE. The agency often contracts with private companies for facility management services such as guards, food and maintenance.

(source: Detention Watch Network)

The ruling affects a case in Washington state — which is in the 9th Circuit’s jurisdiction — in which lawmakers in 2021 also banned privately operated immigrant detention facilities, prompting the GEO Group to sue over its facility in Tacoma, the only ICE detention center in the Pacific Northwest.

A district court in Washington stayed proceedings until the California lawsuit was resolved. In a June 22 filing, Washington Atty. Gen. Robert Ferguson wrote that as long as the decision in the California case remains the law of the 9th Circuit, Washington “will not enforce” the statute against the Northwest ICE Processing Facility.

CoreCivic, which operates the Elizabeth Detention Center in New Jersey, sued that state this year over a 2021 law banning private detention. The company mentioned the 9th Circuit ruling in its complaint. CoreCivic’s contract expires in August and can’t be renewed under the law.

This month, Democratic Colorado Gov. Jared Polis signed a bill that will end ICE contracts with jails starting Jan. 1, 2024, and prevent future private facilities from operating, while exempting an existing GEO Group-managed facility in Aurora.

In March, New Mexico legislators rejected a proposal to prohibit local government agencies from contracting with ICE, which would have affected three privately run facilities in that state.

Sophia Genovese, a managing attorney with the New Mexico Immigrant Law Center, who worked with lawmakers to draft the legislation, said previous unsuccessful versions of the bill were broader in scope. When deciding what to include in the most recent bill, lawmakers opted to pursue a ban on intergovernmental service agreements, or IGSAs, in part because of the litigation in California, she said.

“Practically speaking, a private prison ban was really difficult to pass in New Mexico, which is so reliant on private prisons,” Genovese said. “We also realized California had its own IGSA ban [from 2017] that was not impacted by the GEO Group decision, so we felt confident because we were just attempting to monitor and regulate local government behavior — not the behavior of the federal government.”

In the meantime, advocates across the country are calling on DHS to cancel the contracts of facilities with a history of problems and release people while their deportation proceedings continue. In New Mexico, one target is the Torrance County Detention Facility. Last year, a federal watchdog urged the immediate removal of all detainees from that facility after finding safety violations and critical staffing shortages.

In response to public outcry, the Biden administration has ended contracts at five facilities, including Yuba and the Irwin County Detention Center in Georgia, where dozens of detained women said they suffered medical abuse.

At a roundtable discussion with reporters in February, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro N. Mayorkas said he is focused on ensuring that detention centers comply with the agency’s standards of care.

“And if they don’t, and they don’t remediate or prove themselves unwilling to remediate, then we will not sustain such facilities,” he told The Times.

Records and a report obtained by The Times detail allegations of widespread medical abuse and forced sterilization against women held at an immigration detention center in Georgia. The report was presented Thursday to Congress.

Silky Shah, executive director of the Detention Watch Network, which monitors state legislation related to immigrant detention, said California lawmakers have been laying the groundwork for other states to restrict immigrant detention since the 2017 IGSA ban.

That ban followed an era under the Obama administration of increased collaboration between local police and immigration agents. Advocates turned their focus from proposing reforms at the federal level to the local and state levels.

“This is what advocacy is — you have a win, you have some drawbacks,” Shah said of California’s failed private detention ban. Still, she credits state regulation with contributing to lower overall detention numbers.

Oregon has the strongest antidetention policies in the country, she said, with laws banning IGSAs, blocking private detention centers and preventing local law enforcement from assisting immigration enforcement, including by providing jail or prison release dates. The law has not been challenged in court.

Illinois and Maryland have also passed laws aimed at preventing or deterring future for-profit detention centers. Shah said she thinks those laws haven’t been challenged because no private immigration facilities exist in those states, so the laws didn’t force any closures.

In California, advocates are pushing a bill that would block transfers of certain prison inmates to ICE detention and another that would regulate and significantly reduce solitary confinement in jails, prisons and ICE facilities. Last year, state lawmakers rejected a predecessor of the prison transfer bill, and Newsom vetoed the solitary confinement bill.

The Los Angeles City Council this month voted to bar city resources and databases from being used for immigration enforcement, codifying the city’s “sanctuary” policies.

Gonzalez, of Immigrant Defense Advocates, said AB 32’s repeal won’t end California’s fight. The state has the power to further protect detainees, she said, pointing to the fact that California was the first to offer COVID-19 vaccines to detained immigrants and to a recent investigation of unsafe labor conditions at one facility by the state’s Division of Occupational Safety and Health.

California’s private prison ban was an attempt to push state powers as far as they could go, Gonzalez said, given existing laws that already limited the state’s involvement in immigrant detention.

Other states, she said, are still catching up.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.