Column: With just weeks left to strike a deal, it’s time to worry about the debt ceiling

WASHINGTON — It’s time to start worrying about the debt ceiling.

The federal government is careening toward its borrowing credit limit, beyond which the Treasury won’t be able to pay all its bills.

The consequences could be truly catastrophic — a global financial crash — or merely damaging: a jump in interest rates, a plummeting stock market and a more likely recession.

Last week, Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen said the “X Date,” the day the money runs out, could arrive as soon as June 1.

The problem, of course, is politics.

President Biden wants Congress to lift the debt ceiling without significant conditions, just as it did three times when President Trump was in the White House. But the new Republican majority in the House wants to force Biden to accept deep spending cuts and scrap some of his favorite programs.

“They’re trying to hold the debt hostage,” Biden complained Friday.

Republicans have used the H-word too.

“It’s a hostage that’s worth ransoming,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said after a previous debt crisis.

Both sides insist they’re determined to avoid a catastrophic default. But playing chicken over the debt ceiling is a bit like the nuclear balance of terror: Neither side wants a conflagration, but they could easily stumble into one.

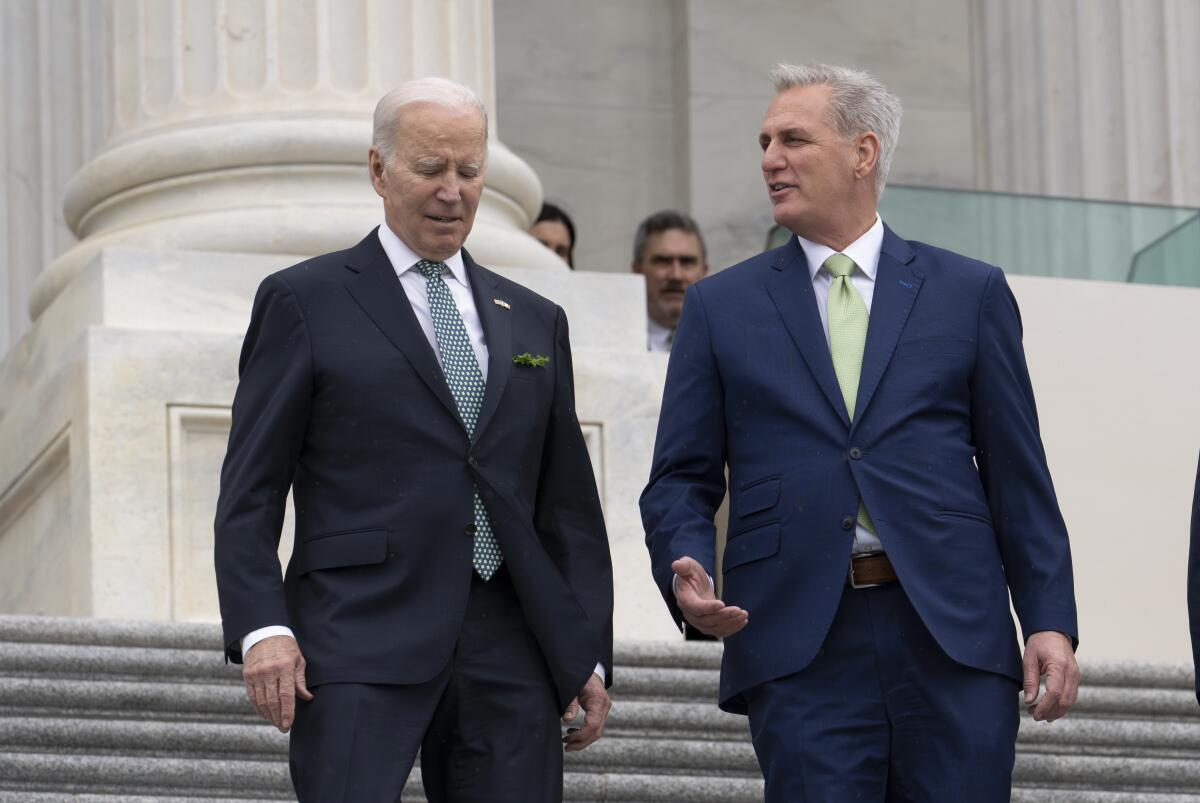

Political polarization has made the problem harder to solve. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) has his job thanks to the hard-line Freedom Caucus, which has long opposed raising the debt ceiling under any circumstance.

In theory, there are plenty of ways to solve this problem — the debt ceiling has been raised seven times in the last decade — but most would require both sides to make painful concessions.

“The debt ceiling fight is like a kidney stone. You’re going to pass it; it’s just a question of how painful it’s going to be,” said Amy Walter, editor of the Cook Political Report, quoting a veteran lobbyist.

Last month, House Republicans agreed on an opening bid: They offered to lift the debt ceiling for one year if Democrats agree to cut nondefense spending (except Social Security and Medicare) by an estimated 22%, an extraordinarily deep reduction.

Biden has offered to negotiate over spending cuts, but says he won’t bargain as long as the GOP holds the debt ceiling hostage. He has little choice, however, since Republicans control the House and make up almost half of the Senate.

Talks are scheduled to begin Tuesday at the White House. Neither side expects a quick agreement.

Black voter turnout dropped sharply in the 2020 midterm elections. For Democrats, turning that around will need to be a major priority for 2024.

Biden wants to preserve the ambitious domestic programs he enacted during the last two years, when Democrats held majorities in both the House and Senate. Republicans want to scrap many of those programs, including clean energy, student loan relief and Medicaid expansion. The GOP also wants to cut funding for the Internal Revenue Service, which would have the perverse effect of increasing the federal deficit.

There are several possible solutions.

Republicans could agree to raise the debt ceiling in exchange for serious budget negotiations. But the Freedom Caucus has already rejected that outcome — and if its members bolt, McCarthy could lose the speakership.

The two sides could split the difference: Raise the debt limit once budget negotiations are underway, beginning with an agreement on overall spending levels. But it would still be difficult to reach a deal that can pass both the Democrat-led Senate and the Republican-led House.

If talks with McCarthy bog down, Biden could try to strike a deal with McConnell. That’s what happened in 2011, when then-Vice President Biden and the Senate Republican leader worked out a compromise.

But McConnell has said McCarthy and the House Republicans should take the lead.

Perhaps most likely, the two sides could decide they need more time and lift the debt ceiling while negotiations continue.

With a presidential campaign underway, these maneuvers are also about who will be blamed if something goes wrong.

Both sides claim the public is on their side. They’re both half right. Republicans point out that most voters don’t want to increase the national debt, and that’s true. But Democrats point out that most voters don’t like the deep spending cuts the GOP has proposed — also true.

A Washington Post-ABC News poll last week found a strikingly symmetrical response, with 78% of Democrats saying they’d blame Republicans if the government defaulted on its debt, and 78% of Republicans saying they’d blame Biden. Independents were divided, but slightly more inclined to blame the GOP.

One missing factor: Wall Street and the business community haven’t weighed in. “They seem to assume that it will all get worked out,” a Democratic aide told me.

That was true for past debt ceiling battles — three during the Trump administration and no fewer than six during the Obama administration.

But this is a more polarized era, with more members of Congress — especially on the right — who have gained power by refusing to compromise.

Solving the impasse may depend on McCarthy’s wisdom and courage, two commodities that have not been reliably measured. He has little experience as a bipartisan deal maker.

The chances of missteps and miscalculations are higher.

That makes the chances of a catastrophic default or a damaging near-default much greater than before.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.