Having elected House speaker, Republicans try governing

WASHINGTON — Electing the House speaker may have been the easy part. Now House Republicans will try to govern.

Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) passed his first test late Monday as Republicans approved their rules package for governing House operations, typically a routine step on day one that stretched into the second week of the new majority. It was approved 220 to 213 on a party-line vote with one Republican opposed.

Next, the House Republicans easily passed their first bill, legislation to cut funding that is supposed to bolster the Internal Revenue Service. The bill hit a snag before votes because the budget office announced that rather than save money, it would add $114 billion to the federal deficit. The measure flew through on another party-line vote, 218 to 210, though it has almost no chance of passage in the Democratic-controlled Senate.

It’s the start of a new era, with House Republicans lurching from one standoff to the next, that shows the challenges McCarthy has in leading a rebellious majority as well as the limits of President Biden’s remaining agenda on Capitol Hill.

McCarthy disappointed colleagues who remember him as a trustworthy, straight-shooting leader in Sacramento, columnist George Skelton writes.

With sky-high ambitions for a hard-right conservative agenda and only a narrow hold on the majority, which enables just a few holdouts to halt proceedings, Republicans are rushing headlong into an uncertain, volatile start of the new session. They want to investigate Biden, slash federal spending and beef up competition with China.

But first McCarthy, backed by former President Trump, needs to show that the Republican majority can keep up with basics of governing.

“You know, it’s a little more difficult when you go into a majority and maybe the margins aren’t high,” McCarthy said after winning the speaker’s vote. “Having the disruption now really built the trust with one another and learned how to work together.”

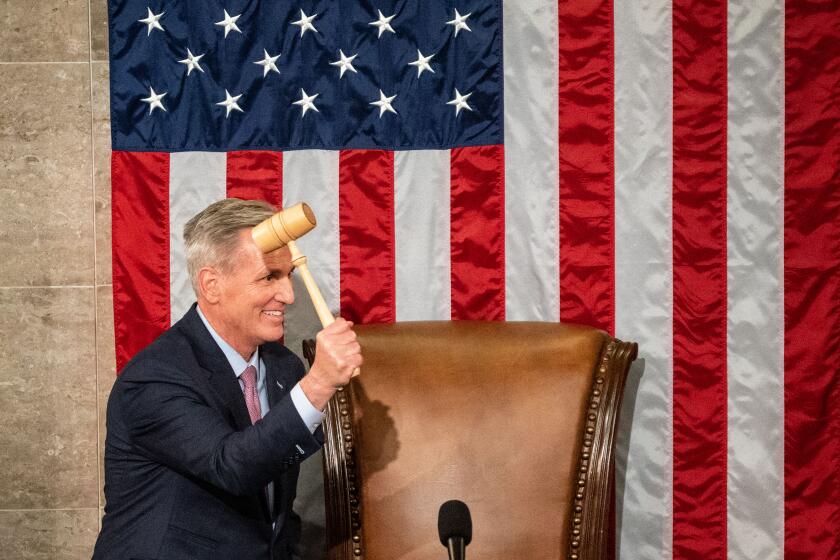

As McCarthy gaveled open the House as the new speaker Monday, Republicans launched debate on the rules package, a hard-fought, 55-page document that McCarthy negotiated with conservative holdouts to win over their votes to make him House speaker.

Central to the package is a provision the conservative Freedom Caucus wanted that reinstates a longstanding rule allowing any lawmaker make a motion to “vacate the chair” — a vote to oust the speaker. Former Speaker Nancy Pelosi had done away with the rule when Democrats took charge in 2019 because conservatives had held it over past Republican speakers as a threat.

Rep. Morgan Griffith (R-Va.) said the rules are about “getting back to the basics.”

But that’s not the only change. There are other provisions the conservatives extracted from McCarthy that weaken the power of the speaker’s office and turn over more control of the legislative business to rank-and-file lawmakers, particularly the far-right lawmakers who won concessions.

The Republicans are allowing more Freedom Caucus lawmakers on the Rules Committee that shapes legislative debates. Those members promise more open and free-flowing debates and are insisting on 72 hours to read legislation ahead of votes.

But it’s an open debate if the changes will make the House more transparent in its operations or grind it to a halt, as happened last week when McCarthy battled through four days and 14 failed ballots before winning the speaker’s gavel.

Many Republicans defended the standoff over the speaker’s gavel, which was resolved in the post-midnight hours of Saturday morning on the narrowest of votes — one of the longest speaker’s race showdowns in U.S. history.

“A little temporary conflict is necessary in this town in order to stop this town from rolling over the American people,” Rep. Chip Roy (R-Texas) said over the weekend on CNN.

Roy praised the new rules Monday, saying he could file a motion “right now” to demand a vote on the speaker — as it has been through much of House history.

But heading into Monday evening’s voting on the rules package, at least two other Republicans raised objections about the backroom deals McCarthy had cut, leaving it unclear if there would be enough GOP support for passage, as all Democrats are expected to be opposed. In the end, Republican Rep. Tony Gonzales of Texas voted against it.

Democrats decried the new rules as caving to the demands of the far-right aligned with Trump’s Make American Great Again agenda.

“These rules are not a serious attempt at governing,” said Rep. Jim McGovern of Massachusetts, the top Democrat on the Rules Committee. Rather, he said, it’s a “ransom note from far right.”

Rep. Ritchie Torres (D-N.Y.) focused his criticism on the GOP’s so-called Holman Rule, which would allow Congress to rescind the pay of individual federal employees: “This is no way to govern.”

McCarthy commands a slim 222-seat Republican majority, which means on any given vote he can only lose four GOP detractors or the legislation will fail, if all Democrats are opposed.

The new rules are making McCarthy’s job even tougher. For example, Republicans are doing away with the proxy voting that Democrats under Pelosi put in place during the COVID-19 pandemic. That means McCarthy must demand greater attendance and participation on every vote with almost no absences allowed for family emergencies or other circumstances.

“Members of Congress have to show up and work again,” Majority Leader Steve Scalise (R-La.) said.

With the Senate narrowly held by Democrats, the divided Congress could still be a time of bipartisan deal-making. Monday saw a group of Republican and Democratic senators head to the southern U.S. border with Mexico as they try to develop an immigration overhaul to curb the flow of migrants.

Boebert, who barely won reelection, has built a national profile with her firebrand style, but some backers say she should try to keep it in check.

But more often a split Congress produces gridlock.

Republicans have been here before, just over a decade ago, when the tea party class swept to the majority in 2011, booting Pelosi from the speaker’s office and rushing into an era of hardball politics that shut down the government and threatened a federal debt default.

McCarthy was a key player in those battles, having recruited the tea party class when he was the House GOP’s campaign chairman. He failed to take over for Republican John Boehner in 2015 when the beleaguered House speaker abruptly retired rather than face a potential vote by conservatives on his ouster.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.