News Analysis: Whoever wins, serving as House speaker will be more like ‘being mayor of hell’

WASHINGTON — Republican leader Kevin McCarthy surely could have seen defeat coming: The wave that swamped him has been building for years.

In 2015, attacks from the right wing drove House Speaker John A. Boehner of Ohio to quit in frustration. Boehner’s successor, Rep. Paul D. Ryan of Wisconsin, stuck it out for just 2½ years before announcing that he, too, would quit the House.

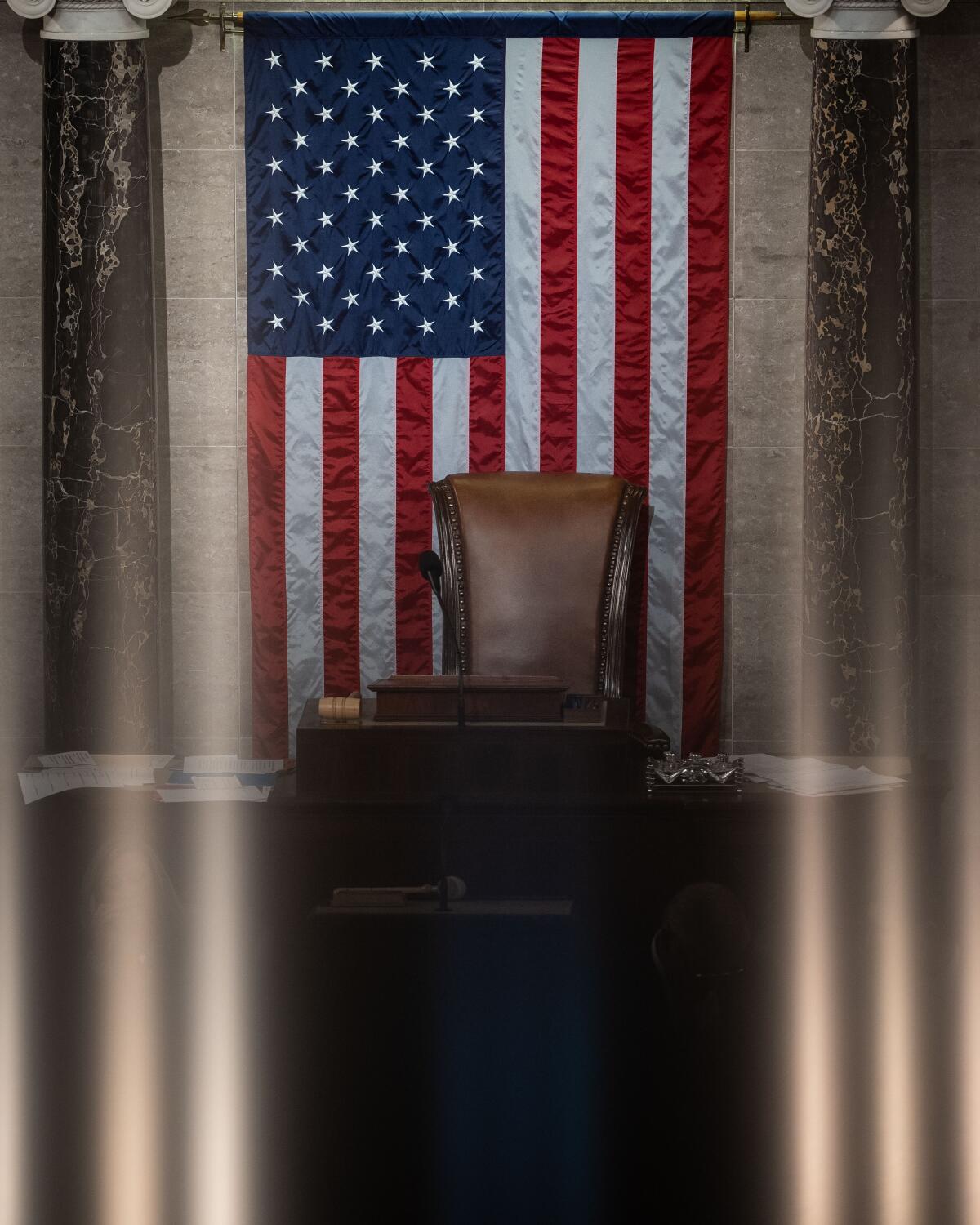

On Tuesday, the division that stymied the last two Republican speakers reached its logical conclusion: For the first time in 100 years, the majority party in the House proved unable to elect its nominee as speaker.

For Republicans, the political pain has probably only just begun, almost regardless of what happens Wednesday when the House reconvenes to try again.

House Republican leader Kevin McCarthy fell short of the 218 votes he needed to succeed Nancy Pelosi as speaker in three roll call votes Tuesday.

The problem for Republicans is that the contest over the speaker’s job isn’t what divides the party. Instead, “the contested race is the symptom of the underlying problems they face,” said Sarah A. Binder of George Washington University, an expert on Congress.

The roughly 20 House conservatives who repeatedly voted against Bakersfield’s McCarthy, who had won the endorsement of the right-flank Republican Freedom Caucus, “aren’t building a coalition” aimed at winning a majority to pass specific policies, Binder said.

Instead, their main power is to “throw sand in the gears” and try to block Democrats and less conservative Republicans from passing key legislation. That gives them little incentive to compromise — either on the speakership or, as Ryan and Boehner both discovered, on bills that leaders in both parties consider “must pass” legislation.

“It’s not clear that they have a price McCarthy could pay” to convince them to support him, Binder added.

Indeed, over the last several weeks, McCarthy made repeated concessions to the right only to see opposition to his candidacy grow.

Whoever eventually emerges as speaker — McCarthy, in the increasingly unlikely possibility that he can win over his deeply entrenched opponents, or another candidate such as Rep. Steve Scalise of Louisiana — will face that same problem over and over in the next two years, Binder and others said.

“It’s going to be hard to pass any major legislation with 20 members of the caucus willing to blow up the place,” said longtime Republican strategist Mike Murphy, now co-director of the Center for the Political Future at USC.

“Being speaker of the House is going to be like being mayor of hell.”

The political danger for Republicans is that many swing voters already see the GOP as too much in the thrall of ideological extremists. In November’s midterm elections, Republicans lost the support of independent and moderate voters, costing them a score or more hotly contested congressional districts they had hoped to win.

Lawmakers on the GOP’s right have a deep commitment to an agenda that was unable to gain majority support even when Republicans held unified control of the government, including sharp cuts in popular social programs, nation- wide restrictions on abortion and a dramatic reduction in the role of government.

This last year, they’ve added to their demands an end to President Biden’s support for Ukraine.

Unable to gain majorities for those positions, they’ve repeatedly tried to extract concessions by blocking legislation that leaders of both parties consider critical. The demands they have leveled at McCarthy have included procedural changes that would make it easier to repeat those efforts.

That has drawn protests from McCarthy’s supporters.

“We are not going to be held hostage by a handful of members. We do not live in a dictatorship,” Rep.-elect Mike Lawler (R-N.Y.) said in an interview with NBC’s “Meet the Press” as the House voted. The conservatives, he said, are “incapable of governing.”

Procedural drama in the House — even the sort that happens only once a century — doesn’t engage the attention of most voters. So the fight over the speakership itself isn’t likely to have a major effect on how the public sees the GOP. But voters do pay attention when Congress fails to pass major pieces of legislation, especially those that affect the economy.

Freedom Caucus members have made clear that their willingness to force a public fight over the speakership is a warmup for battles on those sorts of must-pass bills, including a measure to raise the limit on the federal government’s debt later this year.

Failure to raise the debt limit could cause the government to default on its obligations, which economists have warned could throw financial markets into chaos.

Democrats have been keenly aware of the public’s preference for shows of bipartisanship and compromise, and they have not been subtle in drawing a contrast between the Republicans and themselves.

On Tuesday, Rep. Pete Aguilar (D-Redlands) used the word “unity” or “united” to describe his party at least seven times in his seven-minute speech nominating Democratic leader Hakeem Jeffries of New York for speaker.

And Wednesday, as House Republicans continue to tie themselves in procedural knots over the speakership, Biden will be visiting Kentucky, the home state of Senate GOP leader Mitch McConnell, whom he’ll join for a ceremony touting Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure bill that passed in 2021.

The bill contains roughly $1.64 billion to upgrade a bridge over the Ohio River connecting Kentucky with Ohio. The governors of the two states, Democrat Andy Beshear and Republican Mike DeWine, will also be on hand.

The timing of the visit, which the White House announced on Sunday, was no accident.

“It really speaks to results of the midterm election and what the American people said very loudly and clearly: They want us to work together,” said White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.