They beat election deniers in the midterm elections. Now they’re gearing up for 2024

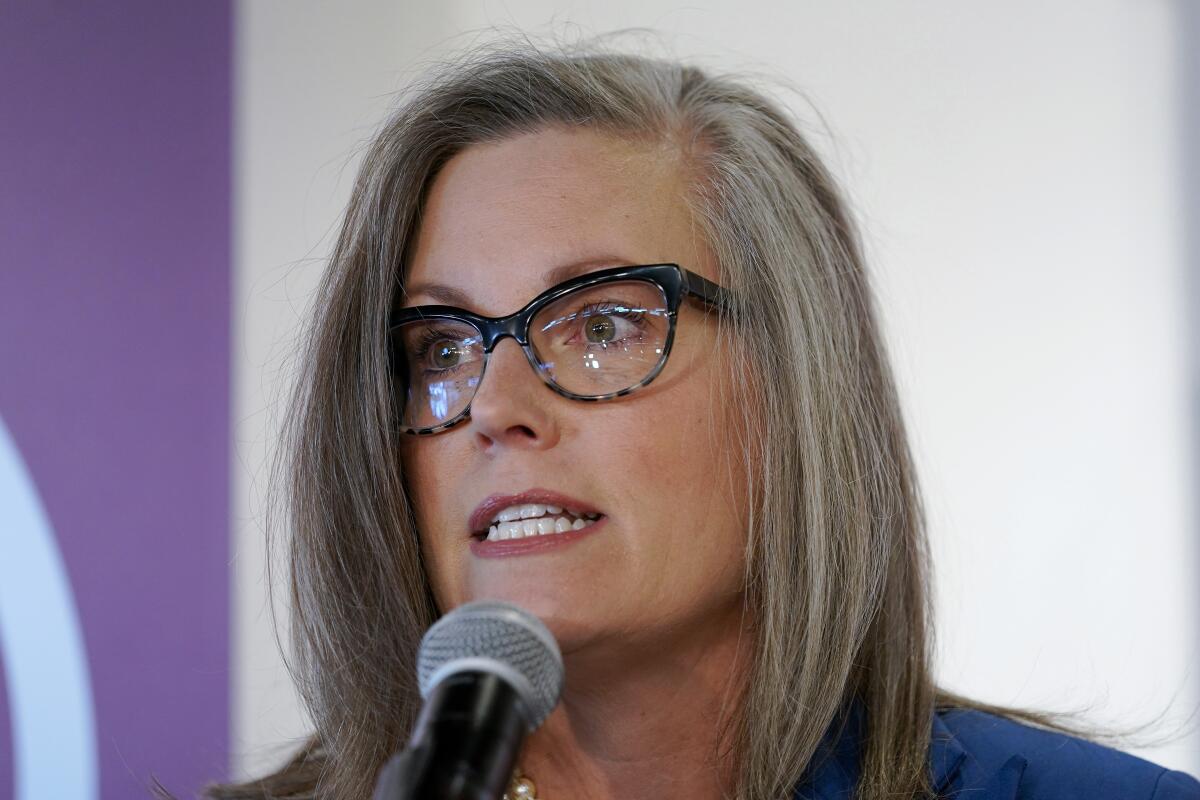

Arizona’s Democratic Gov.-elect Katie Hobbs faced a flurry of criticism in the days leading up to last month’s election.

As Hobbs campaigned on the threat election deniers posed to democracy, Democrats privately worried that she wasn’t present enough, that her campaign was too low-key and that she’d made a terrible decision against debating her Republican opponent, Kari Lake, an ardent supporter of former President Trump who said she would not have certified President Biden’s 2020 win in the state.

But Hobbs found that her plan to characterize the race as “a choice between sanity and chaos” resonated with voters, and she went on to beat Lake by 17,000 votes.

“We had a campaign strategy and we kept [focus] on it, and it was the right strategy,” Hobbs said in an interview. “So, I don’t know why they were worried.”

In battleground states, candidates for offices that play key roles in election administration — secretary of state, governor and attorney general — made defending the electoral process against opponents who had helped spread misinformation a central part of their campaigns. Now they’re gearing up for the next challenge: running the 2024 presidential election.

After races that were seen by many as referendums on election denialism, the winners say that voters selected them to fight back against conspiracy theories and restrictive voting laws. In a bid to bolster their state election systems, they are advocating for new protections for workers, limits on efforts to block the certification of results and increased funding for equipment and security measures.

“I think that 2020 was a precedent-setting election in terms of the loser not accepting the results,” said Hobbs, who rose to prominence over her defense of the 2020 presidential election, which she ran as Arizona secretary of state. “That appears to be a losing strategy, but I don’t think that Democrats can take that for granted. We have to stay focused on the campaign promises we made.”

As secretary of state, Hobbs partnered with Democratic state lawmakers on legislation that would have simplified the way absentee ballots are counted, required county officials to disclose how many uncounted ballots remain when reporting election results and expanded early voting. Hobbs said that legislation will be a “framework” for her administration’s agenda, though it failed to advance and is likely to have a difficult path next year in a Republican Legislature.

In the 2022 midterm elections, hundreds of Republican candidates for governor, secretary of state, attorney general and Congress attempted to cast doubts on the results of the 2020 election or centered their campaigns on baseless fraud theories. Trump made a point of endorsing candidates who helped spread the false claim that the last election was stolen from him due to widespread fraud, particularly those who would be in a position to administer elections in 2024. Trump launched his third presidential campaign last month.

Voters rejected many of his picks, including members of the so-called America First coalition of secretary of state candidates led by prominent election deniers, and Trump-backed gubernatorial hopefuls in Arizona, Michigan and Pennsylvania. Those losses have sparked a reckoning in the national Republican Party.

“The message from the public was that they want to protect their elections,” said Lawrence Norden, senior director of the Brennan Center for Justice’s elections and government program. Election officials “now have an opportunity to leverage that, to ask for more, and to play a role that says, regardless of political party, the role of election officials is to ensure free and fair elections,” he said.

Norden pointed to several areas in which he believes state and federal governments could make progress ahead of the next election, including improving security for poll workers and election staff, preventing the mishandling of election equipment and increasing funding for election offices.

A Democracy Fund/Reed College survey of election officials released last month found that 1 in 4 election officials have faced abuse, threats or harassment.

Cisco Aguilar, Nevada’s incoming Democratic secretary of state, defeated former Nevada state Rep. Jim Marchant, whose coalition of America First secretary of state candidates included those in Michigan, Arizona, California, Colorado and Georgia. Marchant pledged that Trump would be elected in 2024 if they won. All but one of them, Republican Diego Morales of Indiana, lost.

Aguilar pledged during his campaign to help push for legislation making it a felony to harass or threaten poll workers. He said he believes the bill has bipartisan support and plans to discuss it with Republican Gov.-elect Joe Lombardo.

“We need to remind election workers that they’re going to be protected, and that we’re going to have their back,” Aguilar said in an interview. “They need to know that they can go do the job they need to do in a safe environment, without fear.”

A handful of states have passed legislation to protect election workers, including California, where Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill into law in September allowing election workers to enroll in address confidentiality programs to prevent their private identifying information from being maliciously published online.

In Arizona, Democratic attorney general candidate Kris Mayes said she would work within existing state laws to hold people accountable for harassing election workers. Mayes, the projected winner, bested Republican Abe Hamadeh by just over 500 votes. The razor-thin margin triggered an automatic recount.

“We’re going to make sure going forward that anyone who engages in death threats or tries to interfere with our elections will be investigated and, if warranted, prosecuted,” Mayes said.

But obstacles remain for newly elected officeholders who hope to safeguard the electoral process, with some local and state officials making moves that erode trust in the system, including granting third parties unauthorized access to election equipment, or refusing to certify vote tallies and petitions for ballot initiatives.

Last month, officials in conservative-leaning Cochise County in Arizona and Luzerne County in Pennsylvania did not meet legal deadlines for certifying midterm election results. After facing lawsuits, both counties eventually complied.

“There’s still a lot of reason to be worried, in part because there are still places where election deniers have some power,” said Rick Hasen, a UCLA law professor and director of the Safeguarding Democracy Project.

Though there are multiple legal pathways to challenge election results, county officials in Arizona and other states lack the ability to unilaterally withhold election results by blocking certification. Election experts say there is a need to make clear the limits of what officials can and cannot do under state law, as well as the consequences of not following it. Hasen has called for eliminating boards that hold purely ceremonial roles over vote certification.

In Michigan, voters approved a constitutional amendment codifying language that requires canvassing boards to certify election results “based only on the official records of votes cast.” The amendment, which passed with 60% of the vote, also changed state election law by providing nine days of early voting and state-funded drop boxes for absentee ballots.

“That really underscores that we have a mandate, elected officials in Michigan have a mandate, not just to defend democracy, but to work to protect and expand it,” said Jocelyn Benson, Michigan’s Democratic secretary of state, who staved off a challenge from Trump-backed candidate Kristina Karamo.

Michigan Democrats gained control of both chambers of the Legislature for the first time in 40 years. Voters also reelected Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, Atty. Gen. Dana Nessel and Benson.

Benson said she would like to see legislation to increase penalties against people who threaten election workers and to increase transparency in officials’ financial disclosures. She’s also seeking funding from Michigan’s Legislature to implement the state’s new voting procedures.

Benson and other state officials are also anticipating additional election funding at the federal level as Congress considers an omnibus spending bill that is expected to include $400 million in election security grants. Since 2018, Congress has approved nearly $1.3 billion in election grants, after years of sparse funding that followed 2002’s Help America Vote Act, which set federal standards for elections and provided $3.2 billion in grants to states.

Much of the funding would go to local election officials to replace aging equipment. It would also fund the implementation of security measures such as panic buttons, bulletproof glass and metal detectors — “a lot of the stuff that election administrators never had to think about before, but now are sort of standard fare given the new environment that we’re in,” said Adrian Fontes, Arizona’s incoming Democratic secretary of state, who recently went to Washington to lobby Congress for the money.

One of the biggest challenges for election officials may be stopping the spread of misinformation and improving voter trust in the electoral system. Fontes and Aguilar said they plan to travel their states to meet with local election officials and begin building relationships.

Benson said that some state and local election officials have also increased communication to strategize and share ideas, with plans for future virtual and in-person meetings.

“What I anticipate is we’re going to have a much more sophisticated, much more extensive, much more coordinated messaging strategy to push out trusted information, proactively and reactively, and really undermine the effort to misinform voters,” she said.

More to Read

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.