California is still waiting for some election results. Follow the journey of a mail ballot

By election day, vote-by-mail ballots have been marked, slid into an envelope, signed and mailed, placed in a drop box or turned in to a vote center. Their journey is just beginning.

When the ballots arrive at the Orange County Registrar of Voters, a cavernous warehouse behind a cluster of nondescript office buildings in Santa Ana, they go through several steps before they’re counted — all open to public view.

Jeffrey Kontorovsky, an ambassador with the Registrar of Voters, leads daily tours of the facility to explain the process that will determine the outcome of key races.

The observers range from curious to skeptical. They have questions about the security of drop boxes, updates to the county’s voter roll and how ballots are handled when they arrive at the center, Kontorovsky said.

“It’s a detailed process,” he said Monday. “I really want people to have the information. At the end of the tour, when people walk away feeling better — that’s my favorite part.”

Officials working daily since election day — except Sunday — have counted more than 780,000 mail ballots, and still had more than 59,000 to count as of Wednesday night.

With some remaining ballots determining the GOP’s margin of power in the U.S. House — including in the Orange County congressional race between Democratic Rep. Katie Porter and Republican Scott Baugh — voters are still waiting and wondering about the process.

The processing of mailed ballots that arrived on or before election day and those that were dropped off at vote centers is almost complete. What’s left are those deposited in drop boxes on Nov. 8 and those that arrived by mail in the seven days after election day.

“It’s going to take a while because we’re doing our jobs,” said Registrar of Voters Bob Page. “We want it to be accurate and we want to make sure we don’t disenfranchise anybody.”

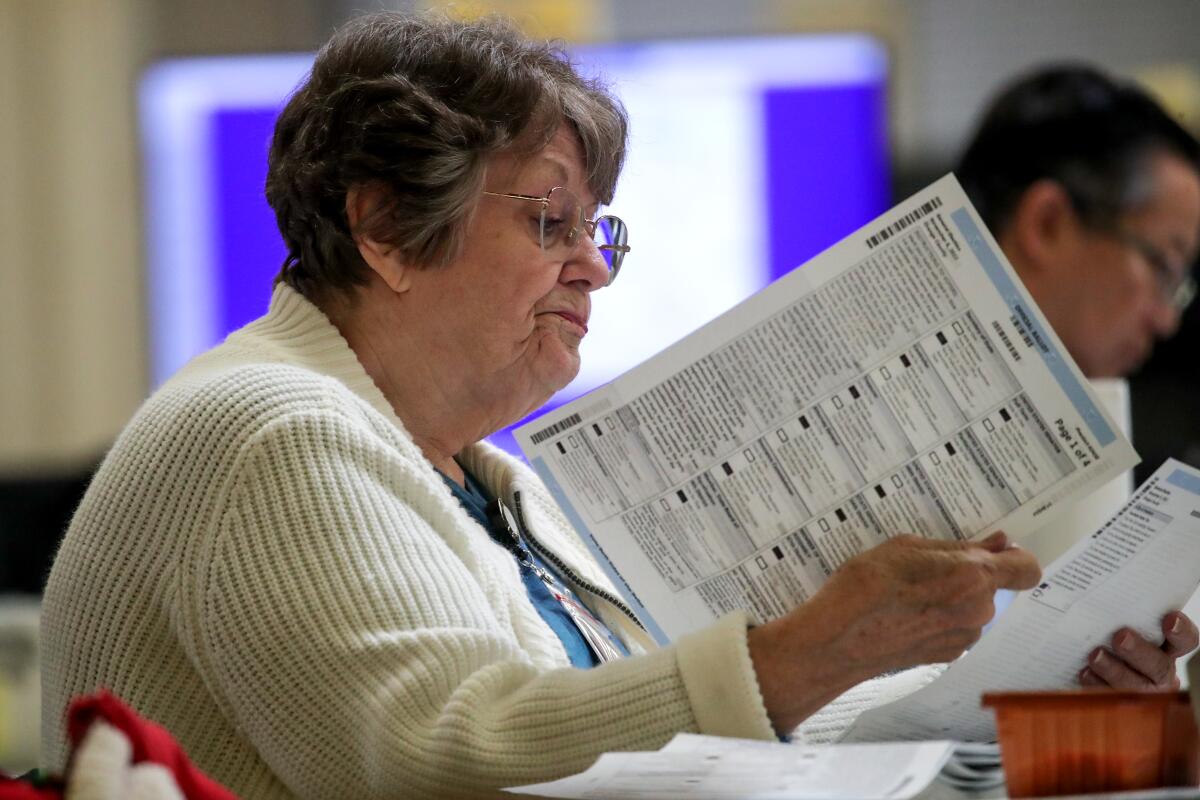

Ballots are first organized by vote center or drop box and then fed into a machine that scans and takes a picture of the outside of the envelope with the voter’s signature. The image is transferred to a computer, allowing employees to match that signature with the one voters used when they registered. Workers zoom in on the autographs to compare the curves and loops.

Their screens are viewable on large monitors just a few feet behind them, where representatives for political parties and the public can watch. On Monday afternoon, roughly a dozen people were there observing.

Some, like Kristin Manna, 51, a political consultant who works on campaigns for Republican candidates, took notes in search of a pattern that might allow them to raise questions about how signatures were being reviewed.

“You can’t challenge signatures, but you can challenge the process,” she said. Typically, this happens if an employee is moving too fast or if there are concerns they’re not following regulations.

If the signature doesn’t match, the worker flags it for another employee to review. If it still doesn’t pass, the ballot goes to a third person who makes the final decision about whether to accept it.

Envelopes that pass the signature test are fed into another machine and sliced open for employees to remove the ballots for inspection and scanning.

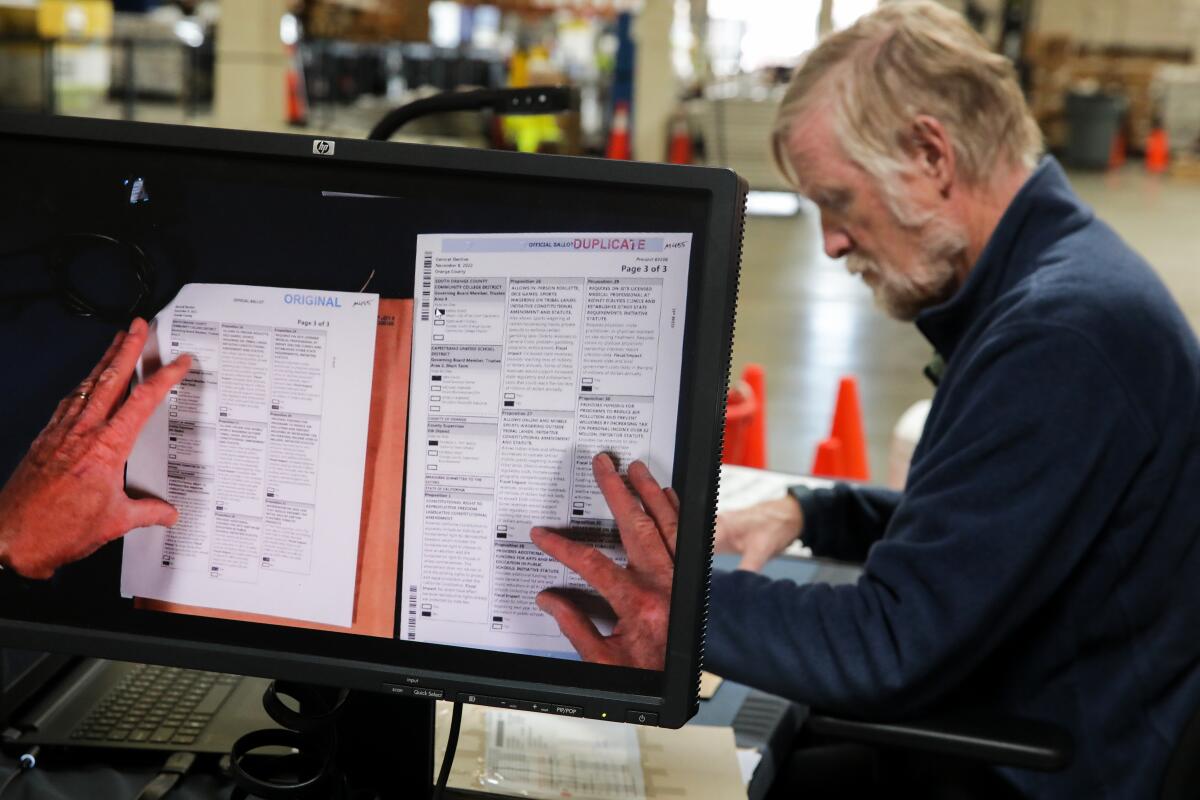

“We’ve seen ballots come in with something spilled on them, torn, even burned,” Kontorovsky said. Those ballots are duplicated and then checked by another election worker before they’re counted.

Ballots that have stray marks or other errors are reviewed and fixed.

A small group watched on a monitor as an employee corrected a ballot on which the voter had bubbled in both the “yes” and “no” boxes for Proposition 30, which would have imposed a tax on income over $2 million to fund incentives for electric vehicles and wildfire prevention. To show the intended choice, the voter circled the “yes” box, but the machine wouldn’t be able to read it.

At the end of the day, the data from the ballots are tabulated, allowing the county to update its vote counts.

If a ballot is rejected, the registrar reaches out to the voter by mail to give them a chance to cure it by signing a document stating it’s legitimate. Certain information about the voter, but not who they voted for, is accessible, and campaigns often mount efforts to encourage them to cure the ballots. The deadline in Orange County is 5 p.m. Nov. 22.

A man wearing a black cap that read “Make Crime Illegal Again” stood outside the scanning room Monday, watching a monitor closely as workers fixed errors on the ballots.

He declined to give his name, but said he showed up because he’s “interested in the integrity of elections.”

“I just feel better if I get to see it myself,” he said.

Observing the vote-counting process is codified into state law, and Page started the public tours this year to give people a better understanding of the operation.

Skepticism about mail voting surged in 2020, when then-President Trump made baseless allegations of widespread mail ballot fraud, which has lingered this election cycle.

“My hope is that people are seeing what we’re doing and we’re addressing any concerns they may have,” Page said. “I mean, for some people this is an emotional issue, so all we can really do is make sure we’re completely transparent.”

Vera Sun, 54, drove Monday from Santa Monica to Santa Ana to observe the counting. She heard about it through her canvassing for Porter (D-Irvine) and initially thought this could be a way to help the campaign.

But when she arrived, she realized there wasn’t much for her to do besides learn, she said.

“It’s boring in a way that’s very satisfying,” Sun said.

As workers and observers streamed in and out of the warehouse Monday, few glanced at a chalkboard mounted high on the wall that shows the unofficial results of the 1970 general election when Ronald Reagan was running for governor.

Kontorovsky likes pointing out the little bit of history on his tours, which are open to the public without reservations, explaining that’s “how elections used to be done.”

A man in attendance offered his own view: “That’s when it worked.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.