MILWAUKEE — Angela Lang has seen the ads attempting to paint Senate candidate Mandela Barnes as soft on crime. The one she takes issue with most features clips of real Wisconsin shootings. As a blurry figure fires into a crowd of people, the shooter is circled in red and Barnes’ name appears on the screen, “implying almost that he was the shooter,” she said.

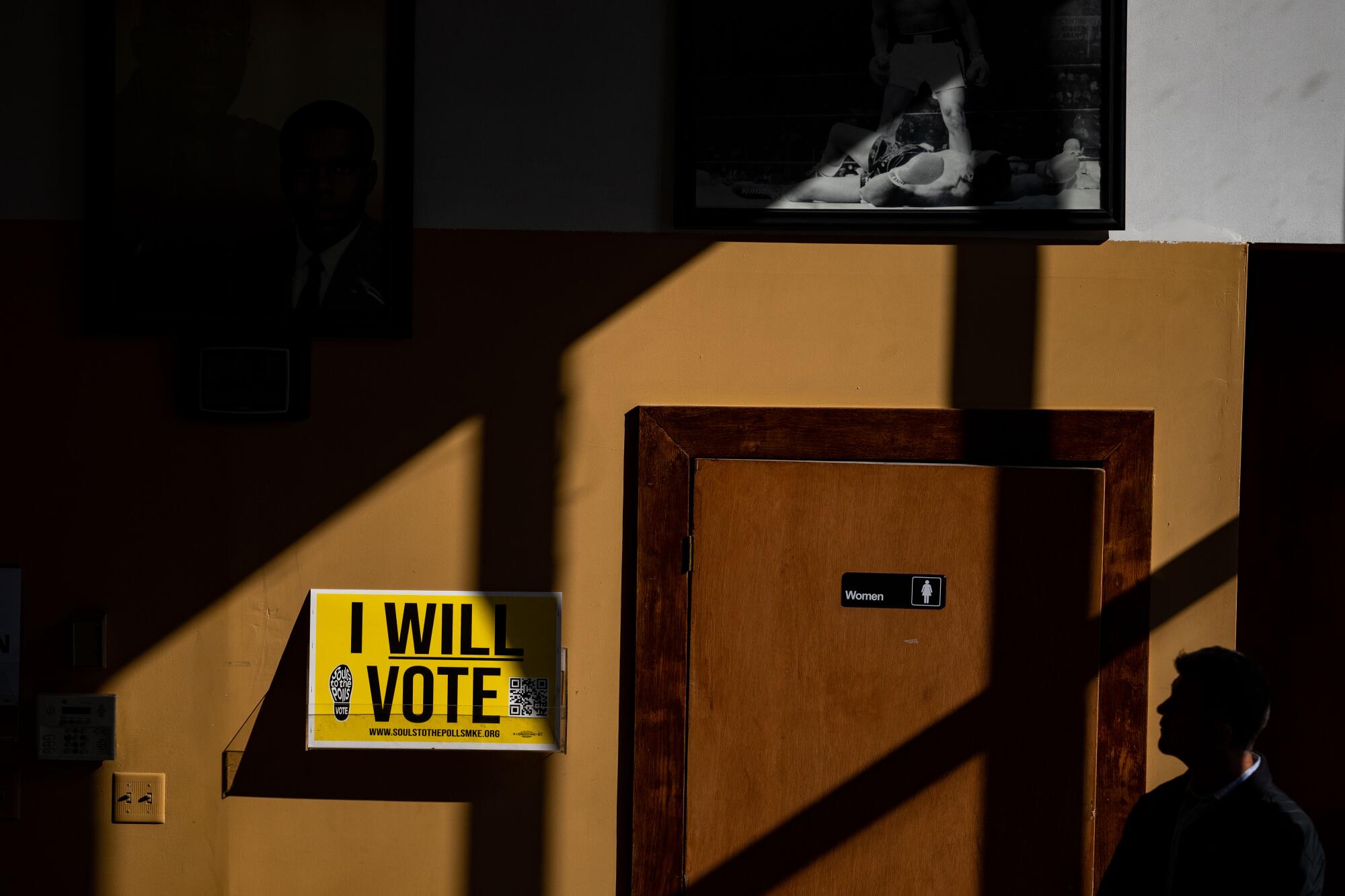

For Lang, the founder of Black Leaders Organizing for Communities, an organization focused on mobilizing Black voters, the attack ads are both infuriating and a challenge to overcome.

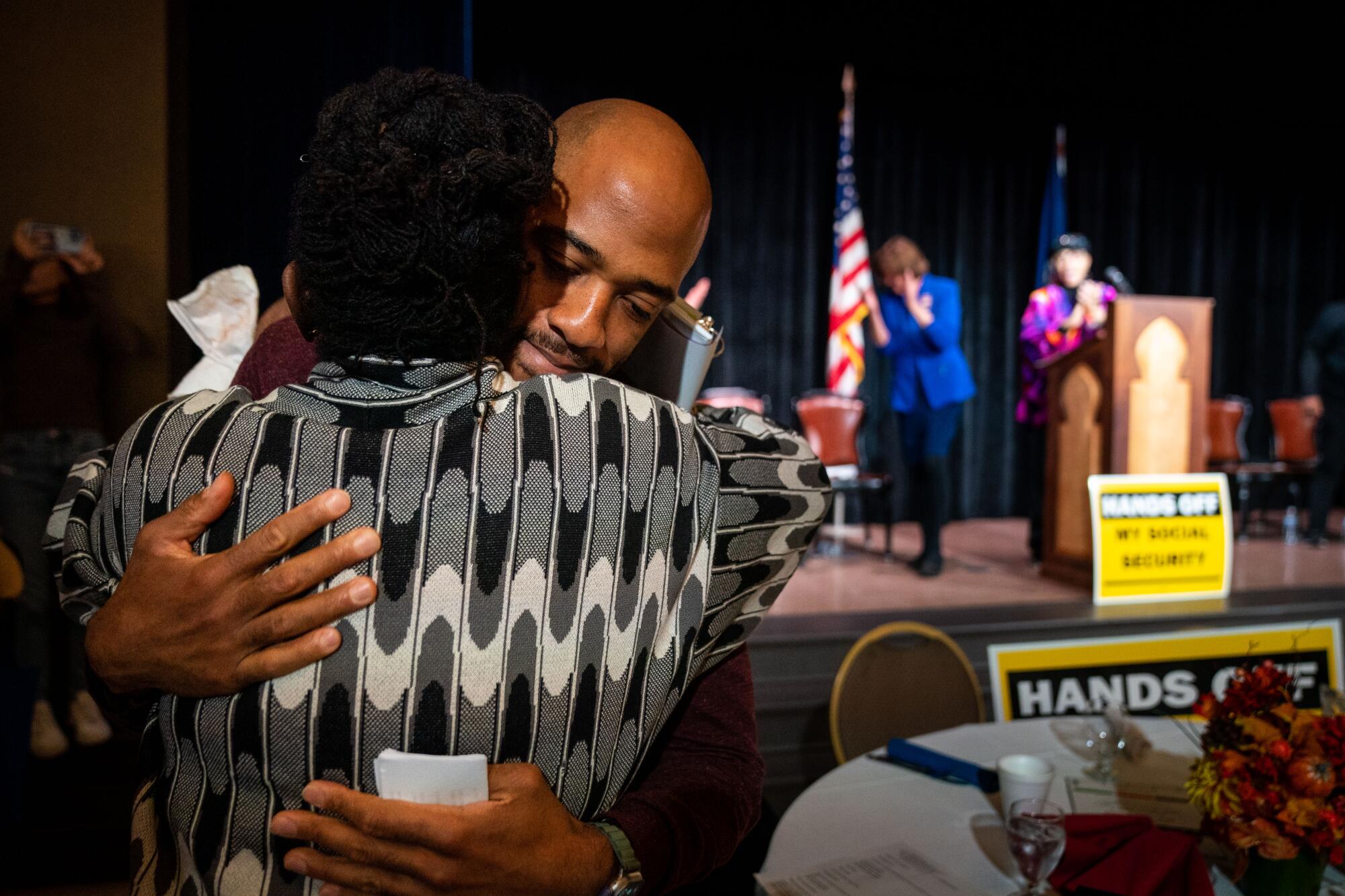

“There is definitely a path,” Lang said, whose group has endorsed Barnes. “One thing that I mention to folks is that whether you’re from the north side of Milwaukee or you’re in the North Woods of Wisconsin, people see themselves in him and his campaign.”

The Wisconsin U.S. Senate race between Barnes, the state’s Democratic lieutenant governor, and two-term incumbent Republican Sen. Ron Johnson has become one of the closest and most contentious in the country. Johnson and his allies have sought to tie Barnes and his policies to high-profile crimes in the state, characterizing his campaign as “radical” or “dangerous.” Though election prognosticators rate the race a toss-up, polling suggests Barnes’ early lead has evaporated, particularly with independents and suburban voters.

The race may come down to whether Barnes, a longtime progressive, can appeal to a broad enough group of voters. In ads, he’s described his path in life as a “Wisconsin story” — union jobs paved the way for his family to enter the middle class — and focused on manufacturing jobs, protecting family farms, public schools and healthcare.

While that story has universal appeal, the specifics resonate most with Black Milwaukee residents, whose support could make the difference in electing the state’s first Black senator.

His grandfather was part of the Great Migration, one of 6 million Black Americans who left the South in the early 20th century in search of better job opportunities in the North and out West. Racist housing covenants restricted Black residents to the north side of the city, and the legacy of segregation is still evident today. The factories closed and the jobs disappeared. Milwaukee’s 53206 ZIP Code, where Barnes grew up, has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country.

“He’s not just talking to Black and brown folks,” Lang said. “He’s building a strong coalition of working-class folks, of farmers, of teachers, of grassroots organizers. And I haven’t really seen an intentional, broad coalition like that basically since [former President] Obama.”

For years Democrats have attempted to bring together the voting blocs — including young people, people of color, white college-educated and suburban voters — that propelled Obama to the White House in 2008 and 2012.

Even now, nearly six years after he left office, Obama is a popular surrogate for candidates seeking to win tough races in states he won. Barnes is one of a handful of Democratic Senate candidates Obama is headlining campaign events for in the coming days — the former president will be in Milwaukee on Saturday — along with John Fetterman in Pennsylvania and incumbent Sens. Catherine Cortez Masto of Nevada and Raphael Warnock of Georgia. Democrats are hoping to maintain or expand their 50-seat majority in the Senate, where Vice President Kamala Harris often casts the tiebreaking vote.

Though Joe Biden narrowly won Wisconsin in 2020, Black voter turnout did not reach the levels of the Obama era. Democratic strategists say the key is increasing those numbers this election cycle.

“In a 50-50 state where everything matters, if the Black vote materializes for Barnes in a way that it hasn’t for other candidates, that could be the ballgame,” said Joe Zepecki, a Democratic strategist who supports Barnes but isn’t working with his campaign.

Voter outreach groups note the systemic hurdles Black voters face, including being disproportionately affected by restrictive voter ID laws. Wisconsin also has the highest incarceration rate for Black people in the country, and people on parole or supervised release for felonies aren’t allowed to vote in the state.

Outside groups have spent more than $46 million against Barnes, according to Open Secrets, most of which has gone toward ads tying Barnes to crime. The largest spenders in the race have been the Wisconsin Truth PAC, which has spent $26 million in the race and $17 million against Barnes, and the Senate Leadership Fund, a super PAC aligned with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) that has spent $23 million opposing Barnes. Democratic groups have spent $33 million opposing Johnson, including $21 million from the Senate Majority PAC, a super PAC tied to Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer. (D-N.Y.)

Democrats across the country are facing a familiar challenge ahead of the November midterm elections, as Republicans attempt to cast their opponents as anti-law enforcement. Those attacks often feature comments Democrats made in the spring and summer of 2020, when the protest movement sparked by George Floyd’s murder by a police officer led to conversations around reallocating some law enforcement funding toward social services.

In response, Democrats have sought to distance themselves from the “defund the police” movement and tout their efforts to invest more in policing.

That dynamic has been at play in Wisconsin, where Republicans have focused on an unsuccessful 2016 bill Barnes sponsored to end cash bail while he was in the state legislature, his past support for a proposal to reduce the state’s prison population and past comments he’s made criticizing police and noting that he’s open to redirecting police funding.

Barnes and his staff have emphasized throughout the campaign that he doesn’t support defunding the police, including in an ad where he says he would “make sure our police have the resources and training they need to keep our communities safe.”

Though the “defund the police” slogan has for some come to mean eliminating law enforcement, many advocates use the term to describe shifting funds from police budgets to social services to help prevent the factors that lead to crime. Republican groups and media outlets have unearthed old interview segments in which Barnes has said police funding could go toward community services.

On cash bail, Republican ads have zeroed in on the 2021 Waukesha Christmas parade attack, when Darrell Brooks drove an SUV into a crowd — killing six people and injuring scores more — while out on bail set at $1,000. Brooks was found guilty of all charges, including homicide, this week. The attack sparked debate over cash bail in the state, where under state law bail is primarily used to make sure people show up to court, not to prevent the release of people who could harm members of the public.

“Between the Waukesha Christmas Parade Massacre and the soaring murder rates in Milwaukee, Wisconsin voters are seeing the firsthand effects of a soft-on-crime liberal agenda,” Alec Zimmerman, Johnson’s communications director, said in a statement to The Times. “Barnes and his allies in the media can’t defend the dangerous impact these policies are having on Wisconsin communities.”

The bill Barnes co-sponsored would have ended cash bail but allowed judges to block a person’s release if there was clear evidence of a risk to the public. Barnes has claimed his bill would have prevented Brooks from being released, which independent fact-checker PolitiFact rated “mostly true.”

Critics, including groups that support Barnes, say several of the ads against him have used racist tactics, such as darkening Barnes’ skin tone in images or highlighting crime in Milwaukee, which has a 40% Black population, to drive up safety concerns statewide.

“Some of us are furious about it,” said Calena Roberts, a field director for the SEIU Wisconsin state council based in Milwaukee, which has held protests denouncing the ads. “It may be hurting [Barnes] from the suburban standpoint, but it’s not hurting him in our communities.”

Barnes and Democratic groups have gone on the offensive, attacking Johnson over his proposal to change Social Security funding from guaranteed to discretionary, his “A” rating from the NRA and his opposition to gun control legislation, and his past support for restrictions to abortion access. As a senator, Johnson has co-sponsored legislation that would grant a constitutional right to life to embryos and a bill to ban abortion nationwide at 20 weeks.

More recently, Barnes has countered Johnson’s claims about his record on crime by arguing that Johnson, who has supported former President Trump, isn’t supportive of law enforcement because of his attempt to pass along a list of fake Wisconsin electors ahead of the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol and his comments in the wake of the attack. Johnson told a conservative radio show in March 2021 that he wasn’t afraid of the group that stormed the Capitol because they were people who “love this country” and “truly respect law enforcement.”

A recent Marquette University poll that asked voters if they were “very concerned” about various issues found that 74% of Republicans said they were concerned about crime, compared to 55% of independents and 38% of Democrats. Independents were more likely to say they were concerned about public schools, a top concern for 71% of them, while 81% of Democrats said they were concerned about abortion policy.

The same poll, however, found that support for Barnes has plummeted since he won the Democratic nomination this summer, from a seven-percentage-point lead in August to trailing by six points this month. Data compiled by FiveThirtyEight found that Johnson is now leading in polls by an average of 3.4 points.

Rep. Gwen Moore (D-Wis.), a longtime Barnes supporter who has represented the Milwaukee area since 2005, said the lieutenant governor’s allies are trying to disarm the crime attacks by reminding voters that Barnes has lived in those neighborhoods and has a better grasp of what voters there want.

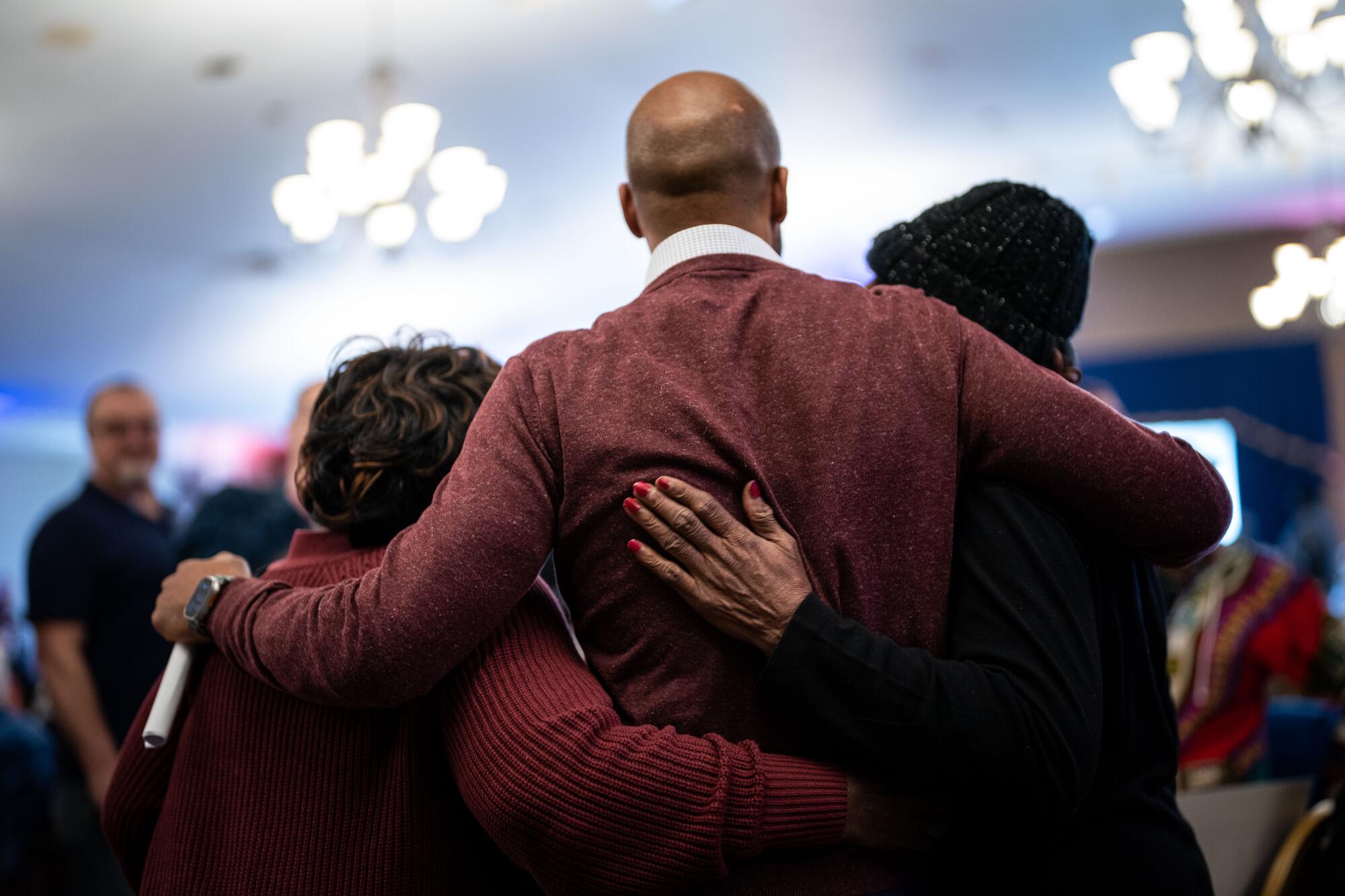

“One of the things that we’re trying to do, these last closing arguments, is go out to our community and say, ‘You know, Mandela,’” Moore said. “He knows that everybody wants security and protection. He also knows that we want accountability, for our institutions to serve us as a community and not work against us.”

Kisha Shanks, a policy director at Milwaukee’s Black Child Development Institute who attended a Black maternal health round table hosted by the lieutenant governor’s campaign, said Barnes’ ties to the north side of Milwaukee are part of his appeal. She grew up in the east and north parts of Milwaukee when the area’s major manufacturing plants were still open and providing jobs. Like Barnes, she witnessed the loss of those jobs and the effect that had on Milwaukee’s Black middle class.

“The community violence, as bad as it is, it’s not because we’re just inherently that way,” Shanks said. “The city of Milwaukee is a petri dish for every social issue you can think of.”

People who aren’t from Milwaukee or familiar with the city beyond its negative portrayal on the news tend to say the solution is to increase policing, she said. But the actual solution is to reinvest in the community, she said.

“We need representation on the Senate floor that understands that,” she said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.